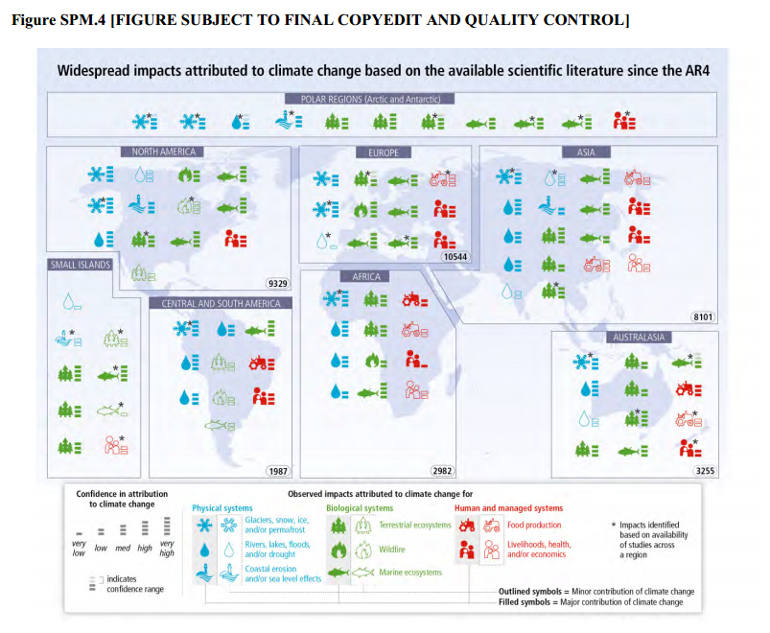

A graphic shows observed global impacts of climate change in areas such as food production, glaciers, health and wildlife. (IPCC AR5 Synthesis Report)

The expected effects of increased climate change during the next century will disproportionately affect the poor and other vulnerable communities.

That conclusion came not from Pope Francis or an environmentally focused religious community, but from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on Sunday.

In its fifth assessment report (the first published in 1990), the U.N. panel outlined what is known about climate change to date, including what has happened, what is anticipated to come if countries collectively fail to ratchet up mitigation and adaptation efforts, and who will face the brunt of a warming planet.

“Continued emission of greenhouse gases will cause further warming and long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems,” said the report, which was compiled by thousands of scientists.

“People who are socially, economically, culturally, politically, institutionally or otherwise marginalized are especially vulnerable to climate change,” the report continued. The heightened vulnerability, it said, “is the product of intersecting social processes that result in inequalities in socioeconomic status and income,” such as discrimination based on gender, class, ethnicity, age and disability.

The report projected that without additional mitigation efforts, warming will likely exceed 4 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the year 2100 -- or double the increase scientists have deemed allowable while still avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.

A 4-degree increase, the report said, would bring risks of “substantial species extinction, global and regional food insecurity, consequential constraints on common human activities, and limited potential for adaptation in some cases.” Along with it: increased poverty and displacement of people; coastal flooding; exacerbated health problems; and an indirect amplification of the common drivers of violent conflicts.

“These impacts will disproportionately affect the welfare of the poor in rural areas, such as female-headed households and those with limited access to land, modern agricultural inputs, infrastructure, and education,” the report said.

The emphasis on the impact of vulnerable groups is a common point for religious groups when talking about climate change. In September, the Vatican's secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, told a U.N. assembly that climate change "is a very serious problem which ... has grave consequences for the most vulnerable sectors of society and, clearly, for future generations."

As for what’s already occurred, the U.N. report repeated its now-common refrain -- “Human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases are the highest in history” -- and provided other stark observations.

In each of the last three decades, it said that the Earth’s surface has been warmer than any decade since 1850 and called the period from 1983-2012 as “very likely the warmest 30-year period of the last 800 years in the Northern Hemisphere … and likely the warmest 30-year period of the last 1,400 years.” Half of human-caused carbon dioxide emissions from 1750 to 2011 have come in the last 40 years, with 78 percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions from that period tied to fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes.

The leading drivers of a warming planet continue to be economic and population growth, the report said. The effects to date have seen shrinking glaciers, a decrease in Northern Hemisphere spring snow cover, a change in migratory patterns and activities of freshwater and marine species, increased tree mortality worldwide, and more frequent instances of extreme weather.

In addition, the report said it is “very likely” the number of warm days has increased while cold days have decreased, heat waves have become more frequent in Europe, Asia and Australia, and likely heavy precipitation has increased in regions.

To curb current warming projections to 2 degrees Celsius or below that of pre-industrial levels would require global greenhouse emissions cut by 41 percent to 72 percent by 2050 (compared to 2010 levels) and that emissions levels approach “near zero or below in 2100.”

Making such a scenario a reality, however, would take substantial changes in nations’ investment patterns, estimated as an increase of several hundred billion dollars annually before 2030 in low carbon electricity supply and energy efficiency. The panel projected that the costs of mitigation would reduce global economic growth by roughly .06 percent annually and that delaying action further would only raise the bill.

Other mitigation steps include carbon-capture-and-storage technologies and improved carbon sinks, as well as lifestyle and behavioral changes.

“Substantial cuts in greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades can substantially reduce risks of climate change by limiting warming in the second half of the 21st century and beyond,” the report said.

Should such steps not be taken, the risks of continued warming become more probable, particularly for the poor.

“From a poverty perspective, climate change impacts are projected to slow down economic growth, make poverty reduction more difficult, further erode food security, and prolong existing poverty traps and create new ones, the latter particularly in urban areas and emerging hotspots of hunger,” the report said.

The U.N. climate report provides a lens ahead of the next round of global climate negotiations, set for Dec. 1-12, in Lima, Peru. The 20th Conference of the Parties, as the U.N. climate change conference is formally known, is viewed as an important prepping ground ahead of climate talks set for Paris next year, as climate experts and advocates have targeted 2015 for a climate pact in order for implementation to begin by 2020.

With COP meetings more often than not providing limited results, climate advocates nonetheless are mobilizing to raise optimism, and once again encourage global leaders to strike a deal.

One such effort comes from Our Voices, a multifaith global campaign aimed at building public support for an international climate agreement. Co-coordinated by Fletcher Harper, executive director of the U.S.-based GreenFaith, Our Voices has set aside early December for a series of prayer vigils worldwide.

Called #LightforLima, the events invite people from Dec. 1-6 to hold at-home vigils for a climate agreement, and then to tweet about it with the #LightforLima hashtag. Then on Dec. 7 -- ahead of the arrival of high-level government officials to the negotiations -- Our Voices plans to hold as many as 1,000 public prayer vigils worldwide.

The vigils, Harper said in an Oct. 23 webinar, will serve as a way to let political leaders know “that the faith communities of the world are praying, meditating and hoping that they will do the work that they need to do to set in motion the process so that we can have a strong climate agreement within the coming year.”

To light the vigils, Our Voices has encouraged participants to swap candles for solar lamps through a partnership with SolarAid; $15 provides a lamp for the vigil, as well as donates two to African villages without electricity.

Lamps will be provided for those attending several larger vigils held in capital cities of countries viewed as critical to a climate treaty: Washington D.C., London, New Dehli, Tokyo, Canberra, Australia, Rio de Janeiro, Moscow, and Toronto (Canada’s financial capital).

“These are all countries that are absolutely vital to the climate process, climate treaty process, and we want to show that there is a moral imperative that is being expressed by people of faith around the world in support of this,” Harper said.

Launched in the spring at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, Our Voices has sought to lift up the religious voice in the climate debate, often through social media. Part of the motivation is to push back against media portrayals of faith communities indifferent or skeptical toward climate change, Harper said.

“We don’t believe that that’s the case, and we want to lift up a different narrative, a loving narrative, a better narrative that shows how much we care and what it is we’re doing,” he said.

So far, it has organized “solidarity sea prayers” – where people come together in the ocean and pray for those impacted by climate change – and held a prayer service before the People’s Climate March in New York this September. Plans are in the works for a pilgrimage to Paris ahead of the 2015 climate negotiations.

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]