The panther's greenish eyes, staring directly at the viewer, are hypnotic. Caught in a moment of calm, etched against a golden background, it seems to be waiting. But this is no ordinary painting.

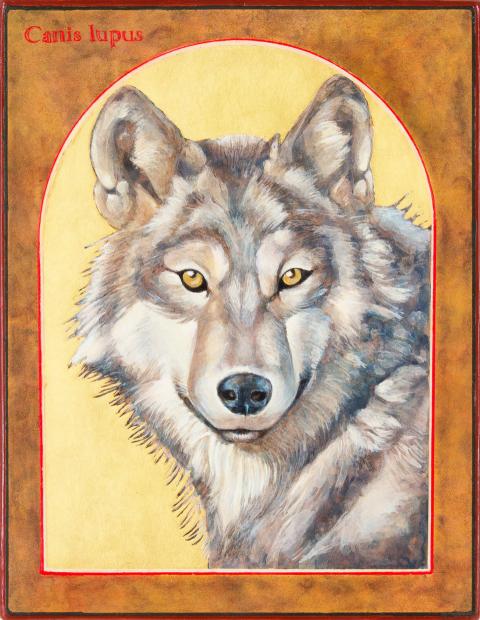

The Florida panther is an icon, part of a series of endangered species depicted by New York artist Angela Manno in the style of traditional Byzantine icons. A frog, an orchid, an orangutan mother and child, a wolf, a fish — 14 in all. They are art. And they are prayer.

They also reflect Manno's own spiritual journey, from the Catholicism of her childhood to the ecotheology of the late Passionist Fr. Thomas Berry, passing through a Quaker school, a Jesuit university, and Carmelite and Buddhist monasteries.

Angela Manno (Jane Feldman)

"I can navigate all of these different spiritualities — they all are enriching, they all have different qualities," Manno said of the various traditions that infuse her paintings. "What I want to do with my work is to help foster the ecological conversion that is needed in our world."

In his 2015 encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," Pope Francis calls for an ecological conversion that "entails a loving awareness that we are not disconnected from the rest of creatures, but joined in a splendid universal communion. As believers, we do not look at the world from without but from within, conscious of the bonds with which the Father has linked us to all beings."

That theme also runs through the activities of this year's Laudato Si' Week, which began May 16 and will end May 25. The week overlaps Endangered Species Day, May 21, and World Biodiversity Day, May 22, when the Vatican is expected to issue a message as part of the Laudato Si' Festival.

An estimated 1 million species are believed to be in danger of extinction, mainly because of human activity, according to a 2019 United Nations report. Scientists say that nearly all the endangered species in the United States — some of which are among Manno's images — are especially vulnerable to climate change.

Manno came to iconography almost by accident.

During a stint in what she calls "the wilds of Colorado," without the assortment of art supplies she'd left behind in her New York studio, she had a chance to take a workshop from Russian iconographer Vladislav Andreyev.

"I had always been attracted to the gold leaf and the imagery of angels" characteristic of the art form, she said. "So I thought this would be a great thing to do, because you could work really small, and everything's portable."

"Canis Lupus, the Grey Wolf," Angela Manno, 2019, egg tempera and gold leaf on wood (Courtesy of the artist)

From the first lesson with Andreyev, "I was absolutely hooked. Orthodox Christianity is different from Roman Catholicism, and I had no idea — it was kind of like an estranged sibling that you'd never met. I was just completely enthralled by listening to him speaking about the meaning behind the icons."

Icons — images of Jesus, Mary, saints, angels or Bible scenes, usually painted on wood — date to the third century of the Christian era. And though styles have varied over the centuries, there is a consistency in the elements that provides continuity through time.

"You learn theology while you learn to do icons," Manno said. "The original icons are considered windows to the divine. When you know how to read them, they're symbolic."

But even as she practiced traditional iconography in an apprenticeship with Andreyev, Manno's own spirituality — nurtured by the writings of Berry, the Jesuit priest and geologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and theologian John Haught of Georgetown University — was evolving.

"I felt a little restrained by the canon, the images of traditional icons, which [are] basically saints and angels," Manno said. "Because of my understanding of ecology, [I felt that] all of us are derivative of the Earth, and there was no icon of the Earth."

So she made one, which became the first of a series that has sprung from the intersection of ecology, cosmology and Christianity.

"The Earthly Paradise: Icon of the Third Millennium," Angela Manno, 2000, egg tempera and gold leaf on wood (Courtesy of the artist)

For iconographers, "The creation of the icon is a recapitulation of the act of our own creation. Every stage is symbolic," she said.

The board on which the image is painted represents the tree of life. Preparing it by adding 13 layers of gesso, a white paint, "puts you into a contemplative frame of mind," she added.

"When it's done, it's just a blank white surface, which represents pure consciousness. Then you scribe an image into it. The images in traditional iconography are handed down through the ages — they're considered Scripture in pictures, so you don't alter them. There are some choices you make in ornamentation, but that's pretty much it," Manno said

The next step is to place clay over the areas that will then be covered with gold leaf. "Clay represents our physical nature and gold represents our divine nature. When you put them together, it's symbolic that we have both these natures," she said.

"Apis, the Honey Bee," Angela Manno, 2019, egg tempera and gold leaf on wood (Courtesy of the artist)

Then the artist begins adding colored pigments, in stages, each with its own symbolism.

"The first stage represents chaos," Manno said. "If you look at some of my traditional images, you can see the chaos layer kind of showing through the subsequent layers. I like to think about that as after the Big Bang. I'm always relating these stages, the traditional notions, to the new cosmology, which is informed by science."

That was especially true with her icon of the Earth, where she applied color to the continents as she would paint the flesh of a face on a traditional icon.

"Everything came together in that icon," she said. "Not only the physical Earth, which is represented by the globe and the physical atmosphere, but outside it is a halo of gold and rays, which represent the Holy Spirit in traditional iconography."

The result, Manno said, is an image of "the Earth coming into its fullness as a bi-spiritual entity."

She completed that work just as the new millennium was beginning. Hearing more and more about what she calls "the holocaust of nature" sparked the idea of a series of icons of endangered species. For her, that concept was reinforced by the words of St. Thomas Aquinas in Summa Theologica, where he writes that God:

He brought things into existence in order to communicate His goodness to creatures and to represent His goodness through them. And since His goodness cannot be adequately represented by any one creature, He produced many diverse creatures. … Hence, the universe as a whole participates in and represents God’s goodness in a more perfect way than any other creature does.

"What that means to me is that the entire universe is an image of the divine," Manno said. "It's not just human beings. So it was an easy transition to start elevating species to the level of an icon."

As a window to the divine, the icon creates a certain separation between the viewer and the image that Manno maintains in her animal series.

"You don't want it to get too sentimental," she said. "You want to see the essence of that animal that is an image of the divine."

Advertisement

She began with a honeybee in 2016 — because of the threats to bees, but also because she had an image of a golden honeycomb in mind — and gradually included fish, mammals, amphibians, flowers and birds. The plight of the endangered Florida panther moved her to add it. There's also a monarch butterfly and, most recently, an orchid — endangered because of plants being poached from their natural habitat.

Her work draws inspiration from around the world — there are orangutans from Asia, a hummingbird from Mexico and a frog from the Andes, although that image also sprang from a childhood memory of seeing boys torturing one of the small amphibians.

"Gastrotheca Orophylax, The Marsupial Frog," Angela Manno, egg tempera and gold leaf on wood (Courtesy of the artist)

Some of her images are connected with projects of the Center for Biological Diversity, to which she said she donates half of the sale price of her original icons. Her work was on display in a 2019 exhibition in New York called "Endangered Earth," and she is preparing for another at the end of this year. By then, an African elephant and several other images will have joined the series.

Manno sees her work as a reflection of Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." Francis' "insistence that everything is interconnected, and his love of beauty … just reinforces what I'm trying to get across," she said.

That is what Manno hopes others will understand when they view and reflect on her icons.

"The intention is to elevate nature, or other-than-human beings, to their rightful place in the community of beings, and for us to value them as having intrinsic value, not just in terms of what their use is for humans — to see the beauty that emanates from these creatures," she said. "We have to understand them, we have to have a moral transformation and ecological worldview if we're going to overcome the terrible destruction that's happening now."