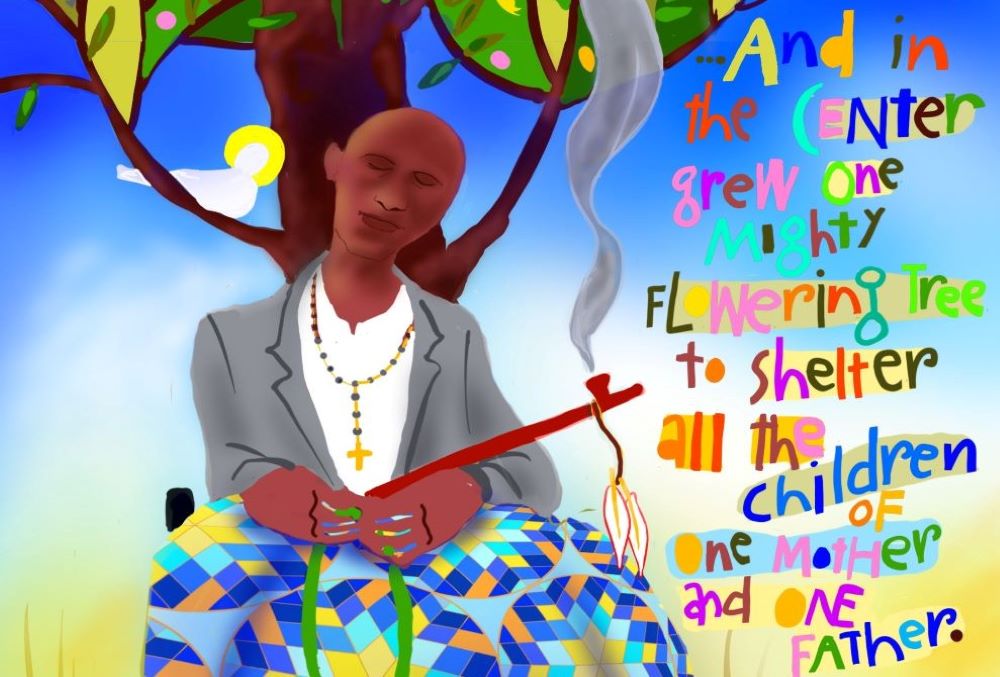

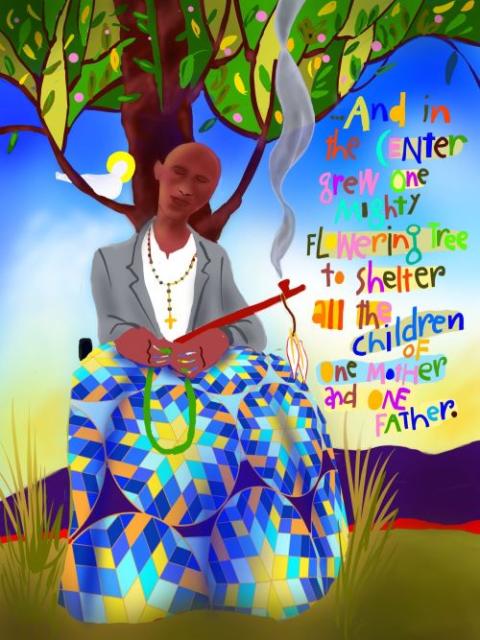

Black Elk/Mighty Flowering Tree" by Brother Michael O’Neill McGrath (Courtesy of Michael O’Neill McGrath)

Few things are more arresting than the smell of burning sweetgrass, the sacred plant that some Indigenous peoples call the hair of Mother Earth. Our Catholic ancestors called it Mary's Grass. Re-connecting with this relative can help us re-Indigenize our faith and heal wounds that riddle Turtle Island and the whole planet.

One of the most important books of the last decade — for me, maybe this century — is Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants (Milkweed Editions). Kimmerer, a botanist and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Band of Oklahoma, started a new conversation between Western science and Indigenous wisdom.

Often, science claims to be the realm of facts and dismisses Indigenous wisdom as fairy tales or myths. In reaction, it's easy to dismiss scientific knowledge as hopelessly imperialistic and destructive. Kimmerer draws on both to give a unitive vision of the whole of creation, with humanity a small yet important part.

Plants are living beings with whom our proper relationship is kinship. Like with other relatives, we have reciprocal responsibilities and dialogue with them.

"Black Elk/Mighty Flowering Tree" by Brother Michael O’Neill McGrath (Courtesy of Michael O’Neill McGrath)

For those of us used to zero-sum competition between humans and the natural world, Kimmerer's main point is surprising: authentic kinship, what she calls a "moral covenant of reciprocity," leads to the flourishing of both humans and other-than-humans, where "people and land are good medicine for each other."

For Natives, Kimmerer's hard-won validation of traditional teachings from the scientific community is a kind of redemption and a call to re-Indigenize all facets of life with the stories and practices she relates.

For non-Natives, Braiding Sweetgrass is not only an important corrective to Western lifeways that set humans over and against the rest of creation, but is also an invitation to become "naturalized to place," a term Kimmerer uses that means to develop new patterns of kinship without appropriating Indigenous culture. Part of that process is looking for analogous teachings in our own cultural and theological heritage.

It turns out the seeds of authentic kinship with the other-than-human world are there in Christian tradition as well.

Relational holism in Potawatomi and Christian origin stories

Kimmerer frames her work with a comparison between the Genesis creation story and the Potawatomi creation story. In contrast to the relational holism of the Potawatomi world, Genesis seems to create a world of exile, where opposition between the human and other-than-human worlds sows seeds of the ecological problems we face today.

Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass was published in 2014 by Milkweed Editions. (Milkweed Editions)

Kimmerer is correct that many people read Genesis this way. But another Indigenous scholar reads the Christian creation story in a way that uncovers relational holism similar to that found in the Potawatomi version.

Dr. Daniel Zacharias is Cree and Austrian, from Treaty 1 territory in Canada and associate professor of New Testament Studies at Acadia Divinity College in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. He is also faculty with NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community, a group of primarily Indigenous scholars and practitioners that are seeking to do Christian theology in an unapologetically Indigenous way.

Zacharias shows how the common Western reading of Genesis is not the most faithful to the original meaning of the text or the most helpful for those striving to live in harmony with the earth. The language of Genesis should be read not as exilic, but rather as covenantal.

"An accurate and more potent translation of Gen 2:15 is: 'Yahweh God took the human and set him in the garden of Eden to serve her and conform to her," ' Zacharias say in "Look to Indigenous peoples to revive true biblical ecology." "For a long time Western Christians have been taught that the land belongs to you. The Bible teaches that you belong to the land."

The translation of Genesis suggested by Zacharias lays a foundation similar to Kimmerer's: Earth is a spiritual mother that humans depend on for life.

Advertisement

Science's hierochloë odorata is 'fragrant holy grass'

The similarities extend to embodied practices, such as with the very species that is the overarching character in Kimmerer's book and representative of Indigenous worldviews: sweetgrass. In the Potawatomi Way, sweetgrass is called wiingaashk, the Hair of Mother Earth. For many North American Nations, sweetgrass is one of the four sacred medicines and often burned in ceremony for its fragrant smoke, not only carrying prayers to the Spirits but praying with us.\

In a Lakota context, it has the power to enact relationality. When burned, sweetgrass' spiritual power "will spread throughout heaven and earth," Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk explained in The Sacred Pipe (University of Oklahoma Press). "It will make the four-leggeds, the wingeds, the star peoples of the heavens, and all things as relatives."

Plants are living beings with whom our proper relationship is kinship

Though "wild," sweetgrass benefits from its relationship with humans. Sweetgrass doesn't easily propagate by seed and must be transplanted. It also needs sustainable human harvesting to thrive. Through gifts of prayer, tobacco and respect — never take the first plant you find, harvest only half, leave the largest — humans help give sweetgrass a home. In North America, the healthiest sweetgrass populations are found close to Native communities

The same species of sweetgrass is native to Northern Europe. The Sami, an Indigenous people from Northern Scandinavia, make use of it. The nomadic reindeer herders often braid sweetgrass, putting the braids in their hats and storing them with their clothes. The Sami also use sweetgrass as a medicine in tea and mix it with tobacco.

Sweetgrass survived the transition to agriculture and remained culturally important among other Northern European peoples as well. Take Poland, where sweetgrass is called żubrówka, or "buffalo grass." The plant is both found in a Neolithic archaeological site in Central Poland and used to flavor vodka, seen by the company to give strength to the European buffalo.

Sweetgrass continued to play a spiritual role during Christian times. The Sami put it in their clothes when they went to church. The people of northern Sweden brought small bouquets of sweetgrass to church. In other places, sweetgrass was scattered on the steps and inside churches on saints' days.

This hierochloë odorata was cultivated in Wrocław University Botanical Garden, Wrocław, Poland. The plant's scientific name means "fragrant holy grass." (Wikimedia Commons/Agnieszka Kwiecień, license: CC-BY 3.0)

Just like in North America, sweetgrass is found near communities that harvested the species. Sweetgrass locations are often ecclesial sights and the historical record notes that it was introduced to Scotland by Prussian monks.

Admittedly, the research on the European side is thinner and the use of sweetgrass hasn't survived with the same vitality as in Native North America. But it is there, hiding in plain sight: The species' scientific name, hierochloë odorata, means "fragrant holy grass." Its sacred nature is embedded in the very language of Western science.

'Naturalized to place' — a Catholic connects with sweetgrass

One European name for sweetgrass is "Mary’s Grass." It may seem to be a superficial detail; Catholics always name things after Mary. But a deep connection to the Potawatomi story can emerge. Mary, after all, is a Sky Woman. She didn't die, it is believed, but was assumed into heaven.

What comes together for me is the completion of a circle. In the Potawatomi creation story, Sky Woman descends to this world with the foliage of the Tree of Life. In Catholic tradition, Mary, like the smoke of the medicine that bears her name, ascends to the heavens and the Tree of Life whose leaves will "serve as medicine for the nations" (Revelations 22:2). "Mary's Grass," as I see it, is a kind of destination story to the Potawatomi origin story.

What's the way forward? Re-Indigenize and become "naturalized to place" in the way Kimmerer outlines in Braiding Sweetgrass. Learn from Indigenous ways without appropriating. Listen to the grass Mary calls her own and maybe even talk back. Make its smell a part of your life that all humans may recover Black Elk's teaching and know "all things as relatives."

Sweetgrass will grow throughout North America; plant it and get to know it as kin.