"You can't address the climate crisis without first addressing the systemic, deeply seated racism that is pervasive throughout American society," said U.S. Rep. Summer Lee during an Aug. 27 event on air pollution at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. (In Solidarity)

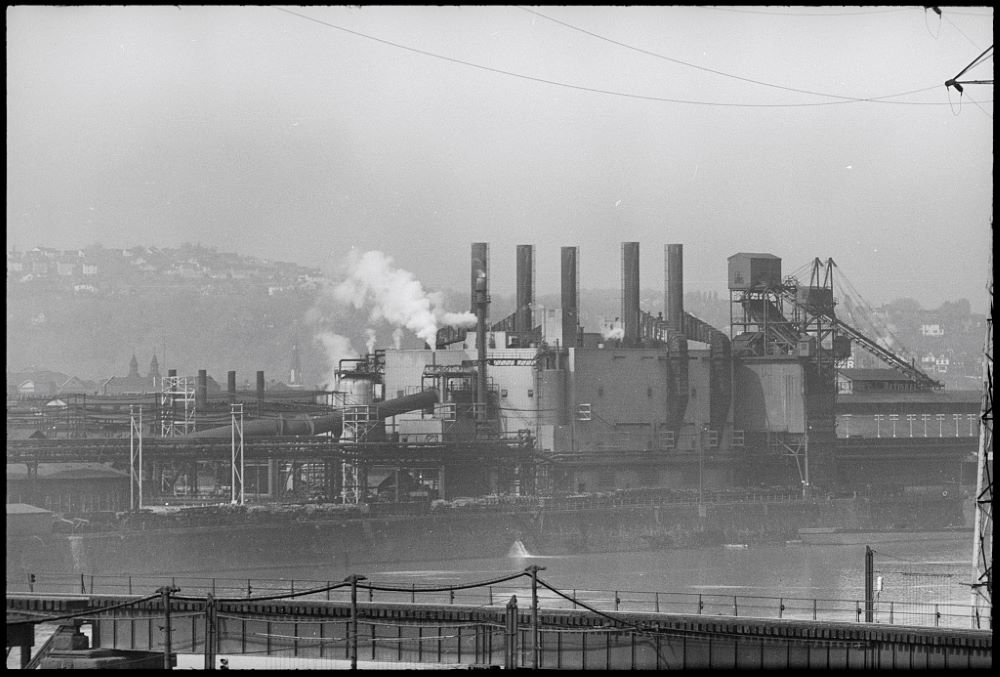

"It's better than it used to be" is a phrase not uncommon around Pittsburgh. It's a reference to thick layers of pollution and smoke that belched from the smokestacks of steel mills and coal plants and blocked out sunlight.

But "better" doesn't mean the problem of air pollution has been solved or that it impacts all parts of Western Pennsylvania equally, said speakers at an Aug. 29 event at Duquesne University on moral and political responses to pollution and climate change.

"Better than it was isn't good enough," said Sr. Kari Pohl, coordinator of justice and peace for the Sisters of St. Joseph of Baden, Pennsylvania, during the hourlong discussion that featured newly elected U.S. House Rep. Summer Lee.

Panelists repeatedly referenced Pope Francis' framing of integral ecology in his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" to highlight connections among pollution, racism, jobs, housing, education and even how industrial facilities are sited.

A steel factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is pictured in this 1959 photo. Pittsburgh ranks as the 14th worst city in the U.S. for annual soot pollution, according to the American Lung Association's 2023 State of the Air report. (Library of Congress/Warren Leffler)

Pittsburgh ranks as the 14th worst city in the U.S. for annual soot pollution, according to the American Lung Association's 2023 State of the Air report. Soot — microscopic airborne particles, known as PM 2.5 — is produced primarily from fossil fuel combustion, through vehicles and power plants as well as industrial facilities and smokestacks.

PM 2.5 particles are easily inhaled and able to penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream, where they can cause a multitude of negative health conditions, such as heart disease, stroke and lung disease in adults and premature birth, asthma and intellectual impairments in children.

This year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has proposed new limits on soot pollution and emissions cuts for fossil fuel-fired power plants, both of which have drawn wide support from faith communities.

Lee, 35, who was elected in the 2022 midterms as the first Black woman to represent Western Pennsylvania, grew up in Braddock, a small suburb in the Mon Valley east of Pittsburgh that is home to the U.S. Steel Edgar Thomson Plant, which has produced steel since 1875.

"It was so normal to me that I didn't even realize that air could get better," she said. "I had not realized that there are places you can go, and communities, other countries that you can go and you can actually breathe air that doesn't smell like rotten eggs."

As steel mills closed across Allegheny County and Pittsburgh's economy slowly shifted toward health care, education and technology, air quality has improved, though it still remains among the most polluted regions in the country. In 2022, the metro region received its first passing grade from the American Lung Association for year-round particle pollution levels. It continues to get failing marks for levels of 24-hour particle pollution.

Expansion of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, as well as new petrochemical facilities, like the Shell ethylene cracker plant that came online in November, pose new threats to health and ecosystems, say local environmental groups. They fear a new "Cancer Alley" forming, similar to the region of southwestern Louisiana, where last week a chemical leak and fire at a Marathon refinery prompted evacuations.

As in Louisiana, air pollution doesn't impact all parts of the Pittsburgh area evenly, said Dan Schied, an associate professor of theology at Duquesne who was part of the panel.

Advertisement

Studies have shown that communities in Allegheny County with low average incomes and high concentrations of people of color are more exposed to health problems in their environments and experience higher rates of asthma attacks, infant mortality and blood lead levels.

"Wherever you see Black and Brown and poor communities, you almost always saw that environmental hazard sitting right next to it," Lee said.

Threats to health aren't limited to Pittsburgh's steel past. Half the state's 12 largest facilities for greenhouse gas emissions are in southwestern Pennsylvania. That includes the Edgar Thomson plant, which along with 11 coal- and gas-fired power plants together produce roughly 20% of the state's total emissions, according to a May report by PennEnvironment.

'This is fundamentally a theological, spiritual problem,'

— Sr. Kari Poh

The Shell cracker plant, located in Beaver County and producing 1 million plastic pellets a year, on its own is projected to emit 2.2 million tons of greenhouse gases annually, or the equivalent emissions from 500,000 vehicles. Shell was fined nearly $10 million in May for exceeding its emissions limits. In 2022, Shell profits doubled to a record $40 billion.

The nation's largest trash incinerator is in Chester, where Black people make up 70% of the population, reflecting a trend of hazardous waste facilities located near communities of color, Pohl said.

Lee added that environmentalism and anti-racism must go hand in hand, and the Protestant politician said that the pope's encyclical underscores the importance for political leaders and others to point out the connections across environmental and other social justice issues.

"You can't address the climate crisis without first addressing the systemic, deeply seated racism that is pervasive throughout American society … because it undergirds every other policy decision that we then make," Lee said.

Rep. Summer Lee speaks during an event on a moral response to air pollution held Aug. 29 at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Also pictured are, from left, Dan Scheid, Scalabrinian Fr. Bill Christy and Sister of St. Joseph Kari Pohl. (In Solidarity)

Lee has helped secure funding for Pennslvyania's 12th District through the Inflation Reduction Act for air quality monitors and brownfield site remediation. She said the law injected a "historic level of funding" for climate justice, including $60 million for environmental justice initiatives, though it's not enough.

"This is not as far as we need to go. But we needed to start," she said.

Asked what local faith communities can do to help address pollution and other environmental issues, Lee said it was especially important for faith leaders to speak clearly about the health and environmental threats posed by fracking and petrochemical facilities and call out misleading statements.

"How you are talking about interconnected issues here, it helps communities to be able to see the greater picture and not just think about things in small silos that makes them feel disconnected from issues that they don't immediately understand fully," she said.

Pohl said that addressing environmental challenges in the Pittsburgh area and beyond requires more "than giving up plastic for Lent" and "requires a full-blown conversion in our relationships": with one another, with God and with creation and natural resources.

"This is fundamentally a theological, spiritual problem," she said.