From left, Jeffrey Sachs, Christine Emba and Cardinal Joseph Tobin discuss capitalism and church social teaching at a Sept. 5 seminar at Fordham University's Lincoln Center campus in New York. (Fordham University/Leo Sorel)

Pope Francis' social teaching offers a dire and needed warning about the twin calamities of economic inequality and climate change, said Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, and Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs at a Sept. 5 seminar at Fordham University's Lincoln Center campus here.

"The system's gangrene cannot be whitewashed forever," said Tobin, quoting the pope's candid remarks via video to the 2017 World Meeting of Popular Movements held in Modesto, California.

Sachs agreed that the pope's sometimes-scathing statements on capitalism are a needed counterweight to American overconfidence that unfettered capitalism can provide a pathway out of the dual crises of climate change and economic inequality.

Sachs, director of Columbia's Center for Sustainable Development, described Francis' encyclical on the environment, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," as "one of the great messages of our time" that "tells us things we will not hear from any other place."

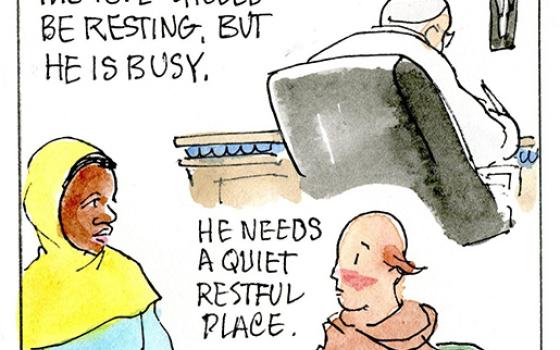

But before the critique of capitalism and church social teaching could be discussed, the metaphorical elephant in the room — the continued onslaught of sex abuse issues afflicting the church — was addressed.

David Gibson, director of the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture, which sponsored the event that drew an overflow crowd to a 400-seat lecture hall, noted that the church has to address the sex abuse crisis. But that doesn't preclude shutting down discussion of Catholic social justice teaching, he said.

"We are capable of being a both-and church," he said.

Tobin described the sex abuse crisis as "the bitter fruit of a toxic culture" and that Catholics have a right to be angry and ask, "How was it allowed to get like this?"

Tobin then addressed the impact of Francis on church social teaching, which has encountered resistance. He noted that he once heard an American bishop in a radio interview explain the pope's critique of capitalism in the fourth chapter of his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium.

"Was the pope criticizing the United States? Is he a socialist?" the radio interviewer asked.

The unnamed bishop said not to worry, that was how Latin Americans talk.

While the tone may have been dismissive, the bishop's analysis has some truth, said Tobin, who in Rome led the congregation for religious life and became known as a strong supporter of Francis.

"Francis' rhetoric can be blunt," said Tobin. But being from Argentina, "he's seen the game played far too long," in which inequality becomes a part of the established order.

Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, speaks at the Sept. 5 Fordham University seminar in New York. (Fordham University/Leo Sorel)

Francis believes, as his predecessors did, that the church should have a voice in shaping the world economic order. The 1971 World Synod of Bishops called upon the church to action on behalf of justice. Pope Benedict XVI, in his 2009 encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, described charity as the value that inspires social justice.

Francis links the two aspects, said Tobin, seeing a necessary critique of capitalism and its resulting economic inequality as part of the church's efforts in evangelization, becoming a voice for the poor in the world.

The pope focuses on seeing social justice issues from the peripheries, through the eyes of those left behind by the world economy. The periphery, said Tobin, is a place often ignored, described by Jesus in Matthew 25.

"It's people we don't see at all," said Tobin.

While the cardinal praised the pope's vision, Sachs was effusive.

He said that Francis is one of the few world leaders who understands the depth of the crises facing the planet and is willing to address them. "We have to listen and understand very clearly," he said about the pope's warnings on the environment.

Sachs, a regular participant at Vatican conferences on global concerns, said the pope's vision is difficult for many schooled in an uncritical Anglo-American view of unfettered capitalism. He said the largely Protestant vision grew out of the nation's founding at the beginning of a new economic order.

"The birth of global capitalism was not nice. It was ruthless in its birth," he said of the European colonial powers taking over native peoples, imposing slavery, and risking all for the cause of greed.

Global capitalism, Sachs said, contained an incredible energy, which inspired European conquerors. It unleashed addictions — such as a hunger for sugar — that reinforced the plantation slave system of the Americas.

Advertisement

It's been up to the popes, since Pope Leo XIII's 1891 landmark social encyclical, Rerum Novarum, to warn against the excesses of capitalism, a tradition that Francis has continued in more direct language.

Francis is warning that the current global capitalist system oppresses the poor and threatens the life of the planet, including efforts by the Trump administration to subvert the Paris Accords on climate change. It is a moral challenge, said Sachs, which often fails to connect with economists who don't appreciate the ethical challenges of the profession. As an economist, Sachs said he was never formally schooled in ethics, a lack that permeates practitioners of his craft.

The pope is warning the world that global capitalism is "putting us in profound peril," said Sachs. As a result, Francis has emerged "as the most important person on the planet."

That voice may well be heard less because of the church's internal issues, acknowledged Tobin, in response to a question raised by panel moderator and Washington Post journalist Christine Emba.

Fallout from the sex abuse crisis affects the power of the church's voice to speak on social issues, said the cardinal. "Have we ever claimed to be perfect? We can't do that now," he said.

Emba asked what the average person can do about overwhelming global issues. Tobin suggested a simple act of solidarity: Invite an immigrant family to dinner. Addressing the big issues on the planet, he said, can begin with a simple act of reaching out to the peripheries in the spirit of Francis.

[Peter Feuerherd is a correspondent for NCR's Field Hospital series on parish life and is a professor of journalism at St. John's University, New York.]