Kat Armas is a Cuban American writer and speaker. She hosts "The Protagonistas" podcast, where she highlights stories of everyday women of color, including writers, pastors, church leaders and theologians. She is the author of Abuelita Faith and Sacred Belonging. (Courtesy of Brazos Press)

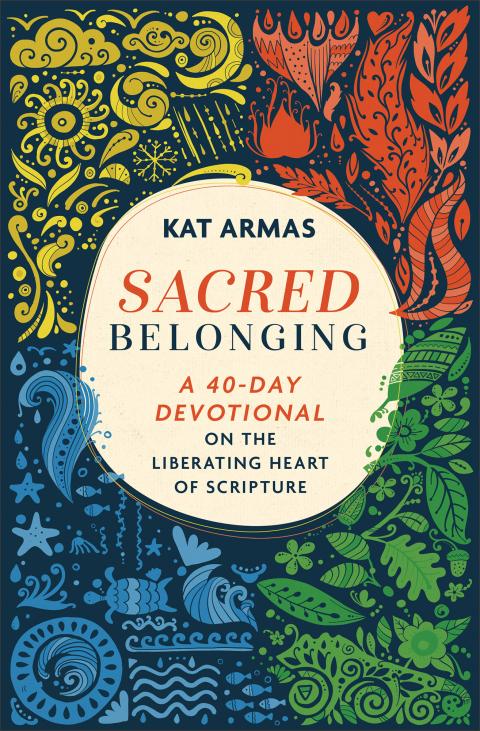

Editor's note: To kick off the new year, EarthBeat is sharing four creation-themed devotions from Kat Armas' book "Sacred Belonging: A 40-Day Devotional on the Liberating Heart of Scripture" (Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, Sept. 12, 2023, used by permission).

Subscribe here to the EarthBeat Reflections e-mail list to receive these devotions in your inbox on Jan. 1, 8, 15 and 22, as well as future spirituality content from EarthBeat.

Look at the birds in the sky.

—Matthew 6:26

The first thing Jesus does after he is baptized is go into the wilderness to fast. Mark says that while he's there, he's with the wild animals and the angels. I often wonder if this is where Jesus's connection with the wild took root. From mountains to trees to vineyards, Jesus was a person in tune with his surroundings and aware of the natural world. His teachings were deeply rooted in the land and the wisdom found in the earth and her creatures.

No created thing was void of value or purpose for Christ. Fish and seeds had the potential to teach the most important things about loving neighbors and taking care of the poor. Observe the birds, Jesus advised, notice the lilies of the field (Matt. 6:26, 28). What if we took him seriously in our daily routines and did just that? What if we truly considered what wisdom might be found in all created things?

It was early spring when we moved into our first home in Tennessee. The flowers had just begun to bud and the birds to nest. I was doing my own nesting too — unpacking my belongings from boxes while my belly grew rounder and fuller each day. Life was flourishing around me and within me.

Taylor and I often spent our mornings sitting in foldable camping chairs in our backyard, watching the sun peek over our wooden fence, the steam rising from our cups of coffee, the oak trees towering above our heads. It was quiet and pleasant. Until it wasn't.

Our peaceful mornings ended when we realized we weren't alone in our new house. A family of starlings had made the wooden slabs of our carport their home before we moved in, and they made sure we knew it.

Each day as we sat to enjoy the morning, we were met with the fury of parent starlings perched above our heads tirelessly squawking at the top of their little bird-lungs in an attempt to defend their space. I thought their behavior was poetic at first — a lesson in parenting as I prepared to become a parent myself. A reminder of God as a mother bird, perhaps, protecting her young. But these sentiments quickly changed when I could no longer relax in my own backyard.

"What kind of birds are those?" I asked Taylor one morning, frustrated.

"Oh, those are starlings."

"What do you know about them?"

"Well, I know they're annoying."

We laughed. A quick Google search informed me that "how to stop starlings from nesting on my roof" is a common concern among folks on the internet. Not only are they ubiquitous and invasive, but starlings are also known for being loud and obnoxious wherever they find themselves.

In addition to validating my irritation, I learned that starlings are able to mimic most sounds they hear: from car alarms to human speech, regularly embedding sounds from their surroundings into their own calls. In fact, their diverse and complex vocalizations make starlings a popular subject of research into the evolution of human language.

The sound of the starling is so unique one even became a muse to Mozart. He was so enthralled by a starling he heard at a pet store, Mozart brought it home and fashioned some of his music after its songs. Learning this amused me. Perhaps it's no coincidence that some of the most hated birds in our midst have also served as inspiration for the world's most renowned musical compositions.

Suddenly I find myself marveling at the starling, remembering Jesus's invitation to notice the birds of the air (Matt. 6:26). So I started doing just that. I watched the starling for weeks, whispering good morning to her each day. She watched me back — a simple kind of reciprocity. I soon began to appreciate her forwardness, her insistence that I notice her.

Advertisement

This is what I love most about Jesus: he had a knack for always pointing us to the overlooked — from the human sitting in the corner to the creature squawking from her nest. They're there, they've always been there, but Jesus invites us to notice, to look closely.

One of my favorite examples of this is found in the story of the poor widow who put everything she had into the collection box of the temple treasury. The narrative begins by saying that Jesus sat and observed how the crowd was giving their money (Mark 12:41–44). I wonder what specific things Jesus was looking for. Was it her? Or was he simply observing, as he often did, noticing the things we tend to miss: the birds, the poor, the flowers? After seeing what she has done, Jesus calls the disciples over and encourages them to observe her too.

I've heard countless sermons praising this woman for her sacrificial giving and prompting that we should do the same. But when I read this story, I don't discern Jesus telling the disciples, "Do what she does." Instead, I discern Jesus saying first and foremost, "Look at this woman." Jesus wasn't giving the disciples a guilt trip, as might be implied. Instead, he invited them simply to notice — the disregarded, the pushed aside, the last people we'd look to for wisdom. Pay attention to her.

Barbara Brown Taylor notes that in order to see all there is to see, we must learn to look at the world not just once but twice. The kin-dom of God is this way: hidden in plain sight (see invitation 7 for more on the kin-dom of God). And Jesus beckons us to look and then look closer.

But this kind of awareness doesn't come easy. To learn from what nature is telling us, we have to stop long enough to notice — to observe, to listen to how it might be speaking or what it might be teaching us — and this cannot be done with an oversaturated mind. Richard Rohr comments that noticing the natural world "takes contemplative practice, stopping our busy and superficial minds long enough to see the beauty, allow the truth, and protect the inherent goodness of what it is — whether it profits me, pleases me, or not."

I think Job was privy to this. He may be known for his unrelenting faith in God, but Job stands out to me because of the way he understood the natural world. When his friend tells him to repent so that his fortune will be restored, Job reminds him that divine wisdom can be found in the places we aren't trained to look. Job says, "Ask Behemoth and he will teach you, the birds in the sky, and they will tell you; or talk to earth, and it will teach you; the fish of the sea will recount it for you" ( Job 12:7–8).

Scripture reminds us that divine wisdom flows through all created things if we're willing to listen. We can discover much from plants and animals that know the intimate details of survival and flourishing. This is one of the greatest parts of being human: finding kinship with all of creation as we learn more about ourselves and the divine.

It's important to understand how the natural world communicates to us. Oftentimes, we tend to reduce both people and nature to empty vessels — listening only for what God might speak through them instead of what wisdom they might be imparting themselves. As Anishinaabe writer Patty Krawec observes, "Listening only for what God might be saying through something diminishes our investment in the world around us and disconnects us from everything, including people, because we don't listen to them either."

After advising his followers to notice the birds of the air, Jesus continues his teaching: "They don't sow seed or harvest grain or gather crops into barns. Yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Aren't you worth much more than they are?" (Matt. 6:26). Through the eyes of Jesus, we get a glimpse of the value of the natural world and the beauty he sees in it.

Sure, a human life is valued more than a bird's life, according to Jesus, but this doesn't mean that birds have no worth. In fact, his point rests on the truth that birds, too, have value. That each one is taken care of by God and provided for.

If anything, it's the birds that remind us that we are worthy.

My neighbor the starling did just that — demanding I notice her and her young. She squawked her truth, reminding me of her value and of my own.

- What wisdom has the natural world communicated to you, whether about herself, yourself, or about the divine?

- How might you engage in the kind of awareness that Jesus had? Where might you take the opportunity to notice, to observe, and to listen?