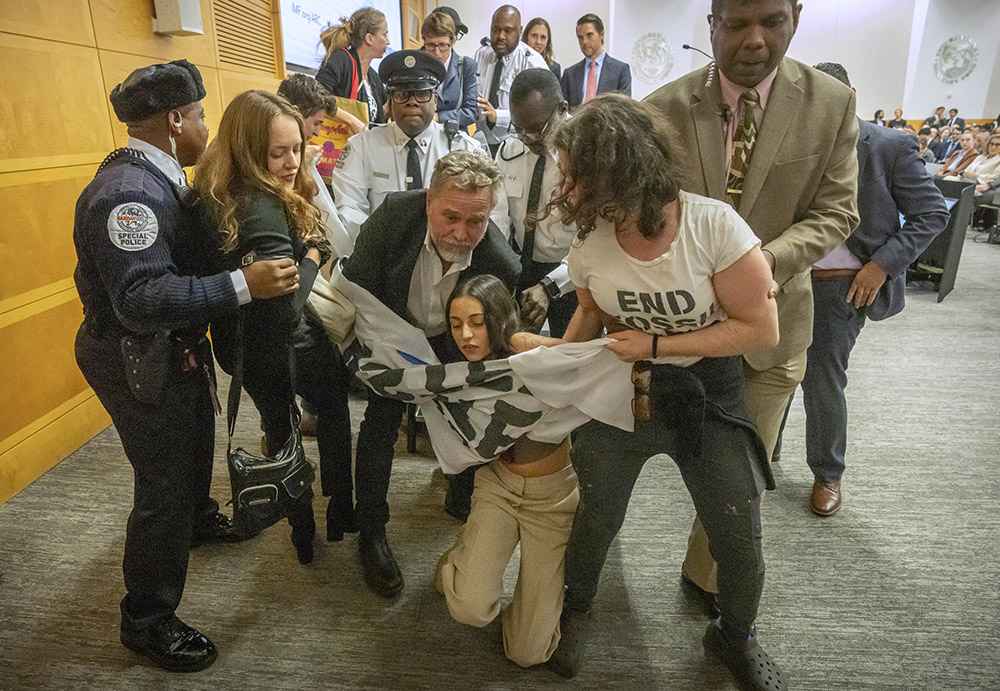

Climate protesters are removed after interrupting a speech by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell at the 24th Jacques Polak Research Conference at the International Monetary Fund on Nov. 9, 2023, in Washington, D.C. (AP/Mark Schiefelbein)

Much has been made of the efforts by climate activists on TikTok. But in order to succeed, the climate movement will have to build community, not only through social media, but through existing community-based institutions like churches and synagogues that are trusted by local people and have historically offered support for movements and activists.

In Saving Ourselves: From Climate Shocks to Climate Action, I describe a three-point plan for transformative climate action that includes building community. I ask key questions about what "community" looks like for the climate movement, and what role traditional sites of "community" like churches could play in helping us get to the other side of the climate crisis.

When we look back at the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, there are lessons to be learned about how to integrate social movement tactics, including civil disobedience, into what Rabbi Jennie Rosenn — the founder of Dayenu: A Jewish Call to Climate Action — calls "the mosaic of social change."

Like the climate movement today, young civil rights activists were frustrated with the lack of results from the more peaceful and less disruptive activism taking place in the movement. Also, like climate activists today, they responded by initiating more confrontational activism.

Advertisement

Today, various types of direct action and nonviolent civil disobedience are being used by climate activists, including throwing soup at the Mona Lisa, blocking roads and entrances to buildings, or confronting politicians in restaurants. But one notable difference between these two movements is the degree to which the groups engaging in disruptive activism are also engaged with and supported by their broader communities — and by churches, in particular.

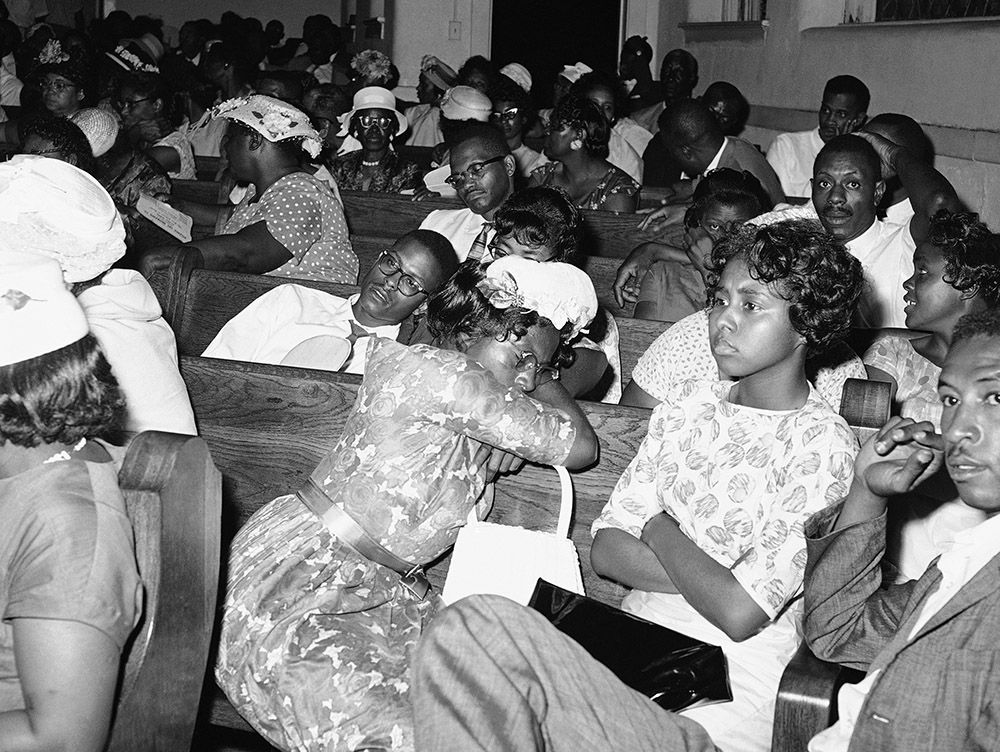

During the Civil Rights Movement, the more confrontational activists were still embedded in the broader community of Black Americans. In his research on the diffusion of confrontational activism as part of the Civil Rights Movement from 1957 to 1960, Aldon Morris explains how Black churches "supplied these organizations, not only with an established communication network, but also leaders and organized masses, finances, and a safe environment in which to hold political meetings."

By contrast, climate groups that are engaging in direct action today work hard to stay anonymous, even from the broader climate movement and other potential progressive allies. This decision is a response to the fact that states and countries are applying more aggressive penalties to climate activism in an effort to deter the spread of confrontational tactics.

The desire to mask one's identity is reasonable, but as one activist lamented to me, this strategy makes it difficult to create community or show solidarity: "How do people know that I will show up for them if everyone's anonymous?"

With the growing risk to activists participating in confrontational tactics, it may be difficult to imagine how activists could safely work within and on behalf of a community without putting the entire community at risk.

People get comfortable in the pews of First Baptist Church on May 23, 1961, in Montgomery, Alabama, as they wait for their own safety to leave an integration rally. White segregationists rioted around the church that night. (AP/Horace Cort)

During the civil rights era, there were also substantial risks to activists participating in the Civil Rights Movement and many activists paid a high price for participating in predominantly peaceful activism. Yet their churches stood by them and continued to act as sites of organization, solidarity and support.

The time is right for churches to step up once again and open their doors, this time for climate activists. Churches offer physical gathering points in communities, and can lean on their legacy around social justice. Most importantly, churches and other locally embedded civic groups provide access to networks of individuals who are connected and concerned about the community.

As I've written about in my previous work, reaching out to convince strangers to care about and act on your cause by knocking on their doors, calling them or even sending them a text message might get them to take a discrete action or even vote in an election. But building on preexisting ties among friends, neighbors, fellow students or even acquaintances who already know one another and have reciprocal social ties has the potential to create more capacity for a community and last longer.

The Civil Rights Movement built this type of network through and among Black churches, which were already trusted and established institutions within Black communities around the United States. The churches connected concerned individuals to a range of groups involved in the struggle for racial justice.

The climate movement should similarly work to build networks of climate-concerned individuals that are embedded in the communities where they live, work and experience climate shocks.

As the frequency of extreme weather, natural disasters and scarcity of resources increases, communities with strong social capital will be better prepared to adapt and recover.

Although the climate movement does not have ties to a specific church or other religious institution, environmental stewardship is a priority for various religious denominations. In recent years, the Church of England and the Catholic Church have both publicly announced their support for a transition away from fossil fuels. Also, organizations that bridge religious and climate concerns have become important partners in the movement.

But we need these types of actions to become more widespread and commonplace, not just to support climate protest, but also to build both social and environmental resilience among non-activist community members who will experience more frequent and more powerful climate shocks in the near future.

As the frequency of extreme weather, natural disasters and scarcity of resources increases, communities with strong social capital will be better prepared to adapt and recover. For example, in a survey of more than 1,000 residents of Ofunato, Japan, after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, the authors concluded that "communal resources, cohesion, and social infrastructure can mitigate shocks and enhance resilience."

As Pope Francis wisely noted in Laudato Si', his 2015 encyclical on climate change and inequality: "The urgent challenge to protect our common home includes a concern to bring the whole human family together to seek a sustainable and integral development, for we know that things can change."

With the world, as Inside Climate News put it, "stumbling past" the 1.5 degree threshold established years ago in the Paris Agreement, the climate crisis is unavoidable and will require everyone working together in their communities to build lasting connections to help us withstand the shocks that will come.