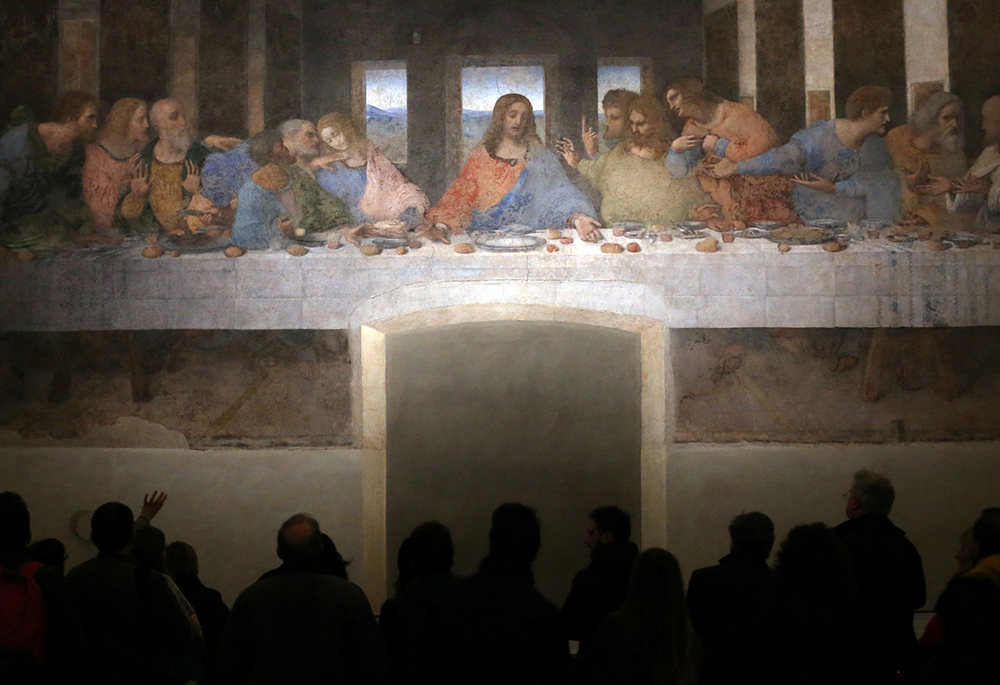

Visitors look at Leonardo da Vinci's "The Last Supper" on a refectory wall at Santa Maria delle Grazie Church in Milan. (CNS/Reuters/Stefano Rellandini)

Growing up in rural South Carolina, I remember checking the ripeness of blackberries that grew along the highway during the long summer months. "Blackberry Time" typically starts the second week of June, but I always checked the blackberries and not the calendar.

I knew summer had ended and the hurricane season had peaked when I saw the Scott family bargain with neighbors to remove fallen trees from their yards. The Scotts recycled the trees to produce hardwood coal at their James Beard award-winning Scott's Bar-B-Q restaurant in Hemingway, South Carolina.

I knew peanuts were in season when vendors sold boiled peanuts (the "ed" in boiled peanuts is silent) in Walmart parking lots. Food historians trace boiled peanuts or "goobers" back to enslaved Africans, who grew peanuts in gardens behind their slave cabins. Today South Carolinians of every race and ethnicity eat boiled peanuts, and in 2006, the South Carolina General Assembly made boiled peanuts the official state snack food.

These memories of foodways connect me to the earth and my folks in a way similar to what Lucille Clifton describes in her poem "cutting greens," where she describes mysterious growth in her awareness of "the bond of live things everywhere."

In the poem, the narrator's ecological consciousness ripened as she entered the luminous darkness of unremarkable cooking practices. While performing the run-of-the-mill task of preparing, mixing and cutting kale and collard greens, she noticed her black hands cutting the greens that rolled black under the black knife on the black cutting board near the black pot in the dark kitchen.

A person's understanding of the world corresponds to how they live in it. Like the narrator, our ecological consciousness develops as we pay attention to the luminous darkness of everyday life.

Advertisement

Many of the ecological stories in the New Testament go unnoticed because we fixate on the cosmic creation stories in the Book of Genesis. Recognizing the power of a good story, theologians repeatedly turn to Genesis to explain social issues such as marriage, human sexuality, gender equality, evolution and climate crises. Like the Titan Atlas, Genesis bears the weight of Christian theology and ethics on its shoulders.

Our overreliance on Genesis' creation stories has transformed these stories into master narratives that justify human domination and subjugation of non-human creatures. According to womanist ethicist Melanie L. Harris, eco-memories — such as mine and Clifton's — can serve as counter narratives to dominant, oppressive master narratives.

Our eco-memories can help us see unrecognized eco-memories in the New Testament. The Gospels do not offer us a cosmic creation story; instead, they present us with the apostles' eco-memories of Jesus' eco-stories.

Like me, Jesus was once a young sun-kissed boy looking for berries along roadways, paying attention to all forms of life. Like Clifton, Jesus was a spoken-word artist who connected little moments in life to big realities. In poetic parables, he compared God's kinship with creation to a farmer planting seeds, wheat among weeds and leaven in dough.

(Unsplash/Nick Sarro)

In Alice Walker's The Color Purple, the flamboyant blues singer Shug Avery says, "It pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don't notice it." In colorful language, Walker sums up one of Jesus' short sayings, "Are not five sparrows sold for two pennies? Yet not one of them is forgotten in God's sight" (Luke 12:6).

Jesus paid close attention to the world around him, and he connected his moral life and God's kinship with creation to the parts of creation that go unnoticed.

One of the most challenging eco-memories about Jesus is when he curses an unproductive fig tree (Matthew 21:18-22). After his death and resurrection, Jesus' disciples linked his interaction with the fig tree to his on-again, off-again relationship with the Pharisees. While I appreciate allegories, I think our attempt to understand Jesus' parabolic sayings and deeds can sometimes distract from the stories themselves.

Our eco-memories can help us see unrecognized eco-memories in the New Testament.

When I hear this story, I feel bad for the fig tree. Was it fair for Jesus to curse the poor fig tree for not producing fruit out of season?

Then I remember how, once upon a time, my ancestors grew protein-rich peanuts in backyard gardens during socially created seasons of famine. I remembered the socially created global food shortage caused by the senseless war in Ukraine. I recall news of possible price gouging by major egg suppliers and worry about the cost of eggs at this year's Easter egg hunts.

In the light of my eco-memories, Jesus' encounter with the fig tree takes on a new light. As he prepared to enter the paschal mystery of his suffering, death and resurrection, Jesus expressed a humbling human need to eat. His hunger connected him to the fig tree in a real way.

People receive bags of relief grains at a camp for the internally displaced people Jan. 22, 2022, in Adadle, Ethiopia. The war in Ukraine, ongoing instability in Tigray and global inflation — peaking at 43% for food items in Ethiopia in April 2022 — placed additional burdens on humanitarian and pastoral efforts in Ethiopia. (CNS/Claire Nevill, World Food Program handout via Reuters)

In his book Food and Faith: A Theology of Eating, Norman Wirzba says, "Eating involves us in a daily life and death drama in which, beyond all comprehension, some life is sacrificed so that other life can thrive."

What hungry person has not cursed the unproductive ground or non-flowering tree? In season or out of season, we are connected to fig trees, eggs, boiled peanuts and Ukrainian wheat fields. Every story of hunger and famine, harvest and banquet, is an eco-story.

At every Eucharist, we recount the eco-story of Jesus' mysterious foodway. We remember his last supper where he celebrated "the bond of live things everywhere" with his disciples.

Every story of hunger and famine, harvest and banquet, is an eco-story.

When I hear the eucharistic story, I imagine Jesus as my mother making dumplings in a sweltering summer kitchen from blackberries picked by her son. In Jesus' hands, the fruit of the earth and the work of human hands becomes spiritual food that awakens our awareness of the interconnectedness of life and salvation. Every Eucharist is soul food, what Francis in "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" describes as an "ecology of daily life" that should remind us of reliance on non-human creatures.

Our particular eco-memories and those from Jesus' life shared with us through Gospel stories ask us to think about how our homes, workplaces and neighborhoods affect how we think, act and live.

As eco-memories shaped Jesus' life and teaching, how are they shaping our lives today?