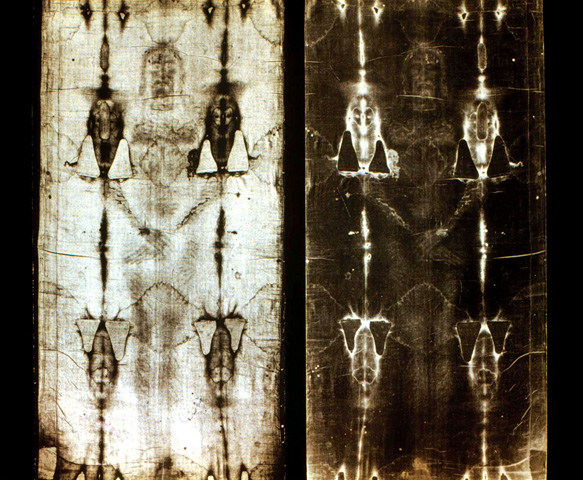

The Shroud of Turin is shown in this positive, left, and negative combo undated file photo. (CNS/Reuters/Claudio Papi)

While the outside world forms general impressions of Pope Francis, insiders tend to see any new papacy through the prism of their own particular interests.

Liturgical traditionalists, for instance, have already voiced some reservations about Francis’ penchant for informality and setting aside the rules, while the church’s peace-and-justice constituency is almost giddy with enthusiasm.

On Saturday, another camp got its first glimpse of what Francis might mean for their concerns, and their early verdict seems mixed: Shroud of Turin devotees.

At the moment, the famed shroud is on a special televised display organized by Archbishop Cesare Nosiglia of Turin. It’s the ninth such public display of Catholicism's most famous cloth since the beginning of the 19th century.

Though there have been various scientific efforts to date the shroud, certitude has been elusive, and opinion remains divided between those who believe the linen cloth was the actual burial garment of Jesus, and those who believe it’s a pious invention from the Middle Ages.

Pope Francis dispatched a message for the new display in which he referred to the shroud as an “icon of a man scourged and crucified.”

The use of the term “icon” rather than “relic” amounts to the usual Vatican caution, given that the Holy See has never officially pronounced on the shroud’s authenticity, though since Pope Julius II in 1506 it has encouraged devotion to the crucified Christ aroused by the cloth.

Benedict XVI also used the term “icon” in his message for a display of the shroud in May 2010, calling it an “icon written with the blood of a whipped man, crowned with thorns, crucified and pierced on his right side.”

In that sense, Francis did not stake out any new position, and he didn’t go as far as some of his predecessors. Pius XII in 1936 called the shroud a “holy thing perhaps like nothing else”, and in April 1980, during a visit to Turin, John Paul II used the magic word “relic,” calling the shroud a “distinguished relic linked to the mystery of our redemption.”

Attentive pope-watchers did note that Francis also said the image of a scourged man had been “impressed upon the cloth,” not “painted” or “depicted.” That language could be construed as consistent with the popular conviction among devotees that the image of a body on the cloth is the result of a release of energy caused by Christ’s resurrection.

In 1978, a team of American scientists carried out an examination of the shroud and concluded there was no evidence of forgery, saying its origins were a “mystery.” A decade later, teams from Oxford, the University of Arizona and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, under the auspices of the Pontifical Academy for Sciences, did radiocarbon testing on small samples from the shroud, dating them to between 1260 and 1390.

Subsequently, however, some critics raised questions as to whether the samples used in the 1988 testing were representative of the whole shroud. Other experts have noted that ancient cloths often date later in radiocarbon analysis than their actual origins, due to bacterial contamination. (It’s a common problem, for instance, in dating ancient manuscripts.)

On Easter Sunday the Italian paper La Stampa carried an interview with Jesuit Fr. Antonio Spadaro, director of the semi-official Vatican journal Civiltà Cattolica, insisting that Pope Francis did not intend to “enter into the dispute over dating,” and that he meant instead to make a spiritual point by saying that the man of the shroud “speaks to the heart.”

In his written message, Francis said that the face in the shroud “invites us to contemplate Jesus of Nazareth. This image … speaks to our heart and moves us to climb the hill of Calvary, to look upon the wood of the Cross, and to immerse ourselves in the eloquent silence of love.”

“By means of the Holy Shroud, the unique and supreme Word of God comes to us: Love made man, incarnate in our history; the merciful love of God who has taken upon himself all the evil of the world to free us from its power,” Francis said.

“This disfigured face resembles all those faces of men and women marred by a life which does not respect their dignity, by war and violence which afflict the weakest.”

At the end, the pope appended a prayer before the crucifix from St. Francis of Assisi.

In any event, enthusiasm for the Shroud of Turin does not seem terribly diminished by the debate over its authenticity.

In conjunction with the TV display, organizers also released a special app developed by the Italian company Haltadefinizione, called “Shroud 2.0,” promising a unique digital experience of the cloth. The app, for iPads and iPhones, drew 15,000 downloads on the first day it was available.

(Follow John Allen on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr)