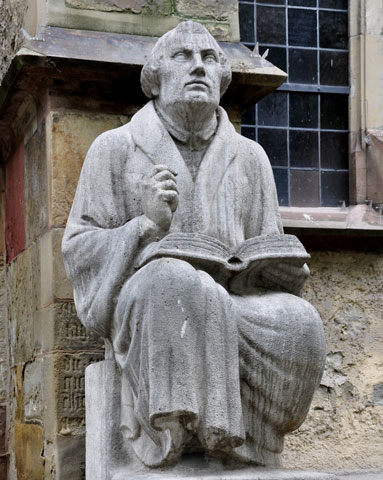

A statue of Martin Luther is seen in Stuttgart, Germany. (Wikimedia Commons/Andreas Praefcke)

BRAND LUTHER: HOW AN UNHERALDED MONK TURNED HIS SMALL TOWN INTO A CENTER OF PUBLISHING, MADE HIMSELF THE MOST FAMOUS MAN IN EUROPE -- AND STARTED THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION

BRAND LUTHER: HOW AN UNHERALDED MONK TURNED HIS SMALL TOWN INTO A CENTER OF PUBLISHING, MADE HIMSELF THE MOST FAMOUS MAN IN EUROPE -- AND STARTED THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION

By Andrew Pettegree

Published by Penguin Press, 400 pages, $29.95

In October 2017, the world will commemorate the 500th anniversary of an act that led to an unlikely, astonishing and peculiarly divisive theological movement. This deed by a man who could not imagine the long-term consequences of his action took place in an unremarkable small town in northeast Germany.

The Protestant Reformation is now said to have begun on Oct. 31, 1517, when a whip-smart but headstrong monk named Martin Luther tacked onto the door of the castle church in Wittenberg a list of 95 objections to Catholic practices. Many had to do with the selling of indulgences, which allegedly would shorten the time people had to spend in purgatory.

This story is well-known and has been told over and over in books. What University of St. Andrews history professor Andrew Pettegree does in Brand Luther, however, is insightful and fresh. He tells the engrossing story of how Luther quickly figured out and eventually controlled the new technology of his age -- the printing press -- to advance the cause of what became the Reformation.

It's an important story told with careful scholarship and elegant writing that takes the reader into the harsh, even brutal, realities of 16th-century Europe.

The odds against Luther and what became the Reformation were enormous, and the fact that it split apart Western Christianity was due in no small part to the preparatory work that Johannes Gutenberg had done by inventing the printing press more than half a century before. Gutenberg's press was the iPhone, the Facebook, the laptop, the Google of his day. And Luther played it for all it was worth. As Pettegree notes, print made Luther a national figure: "German readers devoured every work."

Pettegree reports that "within five years of penning his ninety-five theses, [Luther] was Europe's most published author -- ever."

"In the sixteenth century printers put out almost 5,000 editions of Luther's works; a further 3,000 can be added if one reckons with other projects with which he was involved, such as the Luther Bible," Pettegree writes.

Nearly all of that was published in Germany -- and not in Latin, the language of scholars, but in German, thus making it available to the general populace. (All of this eventually led to the birth of newspapers.)

"Luther," writes Pettegree, "in effect invented a new form of theological writing: short, clear, and direct, speaking not only to his professional peers but to the wider Christian people. This revelation of style, purpose, and form was at the heart of the Reformation."

What may most surprise readers of this worthy book is its account of the contemptuous, nasty, take-no-prisoners tone of the debate over matters of theology (and power). Compared to Luther and some of his Catholic detractors, Donald Trump today sounds like a Sunday school superintendent.

Luther wrote -- and preached -- about the "murderous and bloodthirsty papists." He said over and over that the pope was "the Antichrist" and "vicar of the devil," a "man of sin and child of perdition; a true werewolf."

He used what Pettegree calls "wild, extravagant denunciations" of his critics, vicious language ("the gross asses' heads") that attacked not just the pope and his supporters but also Jews and Muslims, especially after he was formally excommunicated in 1521, when he moved from protest to creating a new church.

"We must fight everywhere against the armies of the Devil," he once wrote. "How many different enemies we have seen in our own time -- the defenders of the pope's idols, the Jews, a multitude of Anabaptist monstrosities, the party of Servetus and others. Let us prepare ourselves against Mohammed as well."

Luther, convinced that he was living in the end times, was intensely focused on making sure people knew the theological truth (his, of course) and making sure they rejected theological falsehoods (others', of course). And he dominated the emerging world of printing to accomplish just that, in one four-year period out-publishing his opponents by a margin of nine to one, though he never accepted payment for his writings.

What is clear from reading this history at a 500-year distance is that Luther's essential theological insight was exactly on target -- that we are saved by grace through faith and not by our works. Although one still can find debate about exactly what that means, essentially all of Christianity today affirms that. But the Protestant Reformation as it developed after Luther has so atomized itself that it is difficult to see how any restoration of Christian unity could ever happen.

The disappointments in this book are relatively minor. It would have been helpful had Pettegree offered a succinct list of the ways in which what became Lutheran worship and practice differed from the Catholic worship and practice it rejected. Readers have to pick that up by hints and indirection.

And Pettegree's description of the 1529 Colloquy at Marburg is so sparse that it almost completely misses the drama. That was a gathering of the leading Protestant lights of the time to try to make sure everyone was on the same page. They agreed on everything except what happens in the Eucharist.

The story of that split is fascinating, but essentially untold in this book. The highlight came when Luther swore to fellow reformer Ulrich Zwingli that he would "rather drink pure blood with the pope than mere wine with the fanatics" (meaning the Zwinglians).

Still, Pettegree has written a significant book about the far-fetched notion that a simple monk from a quiet corner of Germany could -- and did -- create his own brand and change the world.

[Presbyterian elder Bill Tammeus writes a regular column for NCR at NCRonline.org/blogs/small-c-catholic.]