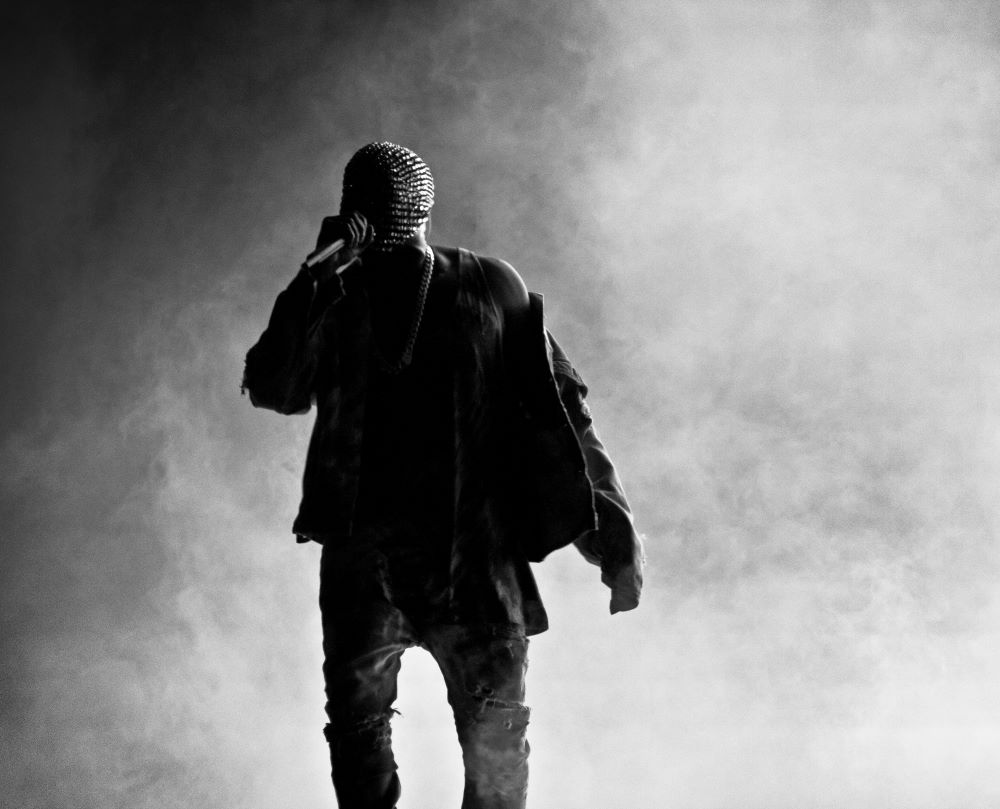

(Unsplash/Axel Antas-Bergkvist)

One early morning during my sophomore or junior year of college, I waited for the 5 Train into Manhattan. I listened to Kanye West's "I Wonder" on a nearly empty and silent train platform and replayed an argument with my mother from the previous night.

I hopped a train that traveled 45 minutes south from my neighborhood in the Bronx to the Gap store at Union Square. I sat in a train cart sparsely dotted with the faces of women and men who, like me, chose sleep or listening to whatever music allowed us to forget that we were awake and working before the sun and the city rose.

Like most mornings, I was angry and listening to Kanye's music. My mother and I rarely saw each other, despite sharing a home. We often yelled and argued when we were near one another because we were both sad and lonely and, in our own ways, dealing with her separation from my father. We never addressed any of this, choosing to repress our anger and resentment with work.

I worked two or three jobs while studying full time, like many Black immigrant students at predominantly white institutions. After morning shifts in Manhattan, and after morning classes, some days I tutored students in Italian; others I interned at a fancy law firm where I spent most afternoons serving coffee and navigating microaggressions specific to European spaces.

Advertisement

Kanye's music kept me focused during what felt like the darkest moments of my life. His music politicized me, from his critiques and struggles with our consumerist culture, to the U.S. government’s treatment of Black people, to his reflections on human insecurity. There was, and often still is, a vulnerability and authenticity to Kanye's lyrics and sounds.

Before I knew words like "discernment" or "consolation" or "contemplative prayer," before the Jesuits I worked with taught me how to talk about my faith – including how I sometimes struggled to pray or believe – I had Kanye's music.

***

The 44-year-old rapper Kanye Omari West was born in Atlanta, Georgia, and raised in Chicago, where his mother taught English at Chicago State University. His father was a former Black Panther and a photojournalist, the first Black photographer at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Growing up, West wrote poetry and rapped, eventually writing his own musical compositions. As a teenager, he was mentored by Ernest Dion Wilson, a DJ and producer known professionally as NO I.D.

After high school, he attended the American Academy of Art College before transferring to Chicago State. He dropped out at 20 to pursue music exclusively.

West first became known for producing for artists like Foxy Brown, the Mad Rapper, Beanie Sigel, Ludacris and Janet Jackson. In 2001, he worked on Jay-Z's "The Blueprint," described by many, myself included, as one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time.

West signed that same year with Roc-A-Fella records, but his first commercial success came in 2003. After a near-fatal accident that shattered his jaw, West wrote, recorded and released his first single, "Through the Wire," the first off his 2004 debut album, "The College Dropout."

A year later, in August 2005, West released "Late Registration," which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard charts and featured Maroon 5's Adam Levine, Brandy and Nas.

Donald Trump and Kanye West meet in October 2018. (Wikimedia Commons/White House photo)

What made his early lyrical politicking feel so groundbreaking is lines like these in "Crack Music," the eighth track on "Late Registration”:

How we stop the Black Panthers?

Ronald Reagan cooked up an answer

You hear that? What Gil Scott was hearin'

When our heroes or heroines got hooked on heroin

Crack raised the murder rate in D.C. and Maryland

We invested in that, it's like we got Merrill lynched.

In September 2007, he released his third solo studio album, "Graduation," a 13-track, genre-blending album influenced by Led Zeppelin, Steely Dan and The Rolling Stones and featuring artists like Daft Punk and Coldplay's Chris Martin. Some of the rapper's most famous songs include "Stronger," "Champion," "Flashing Lights," "Good Life."

His first three albums are not flawless. All contain many of the usual problems found in West's entire discography, except arguably "808s & Heartbreak." There is misogyny, anti-sex worker sentiment, fatphobia and objectification of and violence against women, especially on songs like "Get Em High," "The New Workout Plan" and "Drunk and Hot Girls."

In 2008, West released “808s & Heartbreak,” written a year after his mother died. The album is sonically and lyrically different from the artist's first three. We hear a West who is sad, lamenting, often oscillating between grief and hubris; auto-tune distortion and his use of a drum machine colloquially known as the 808 drum adds to the album's heaviness. And each song title can be read as a look into the rapper's mental state while writing and producing: "Welcome to Heartbreak," "Heartless," "Love Lockdown," "Paranoid," "Bad News," "See You In My Nightmares."

"My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy," released in 2010, features some of West's best production work, especially on songs like "Runaway," "All of the Lights" — featuring 14 artists, including Alicia Keyes, Rihanna, Elton John, La Roux and John Legend — "So Appalled" and "Lost in the World." In 2013 the artist released “Yeezus,” a 10-track album containing some of my favorite West productions, like “Blood on the Leaves,” which samples Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” but also some of the rapper’s worst lyrics on “I’m In It.”

2016’s "The Life of Pablo" is an album that seems to move from one emotion to the next, beginning with a stunning proclamation of faith on "Ultralight Beam" (I'm tryna keep my faith / But I'm looking for more / Somewhere I can feel safe / And end my holy war) and "Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 1" (I just wanna feel liberated, oh / I just wanna feel liberated). On "Famous," "Low Lights" and "Freestyle 4," West is hubristic, arrogant. He moves toward self-awareness on songs like "Real Friends" and "Wolves,” the lyrics capturing how the rapper’s celebrity and personal life, including his mental health and public marriage and separation from Kim Kardashian, has changed since “College Dropout.”

On the self-referential "I Love Kanye," he raps: "I miss the old Kanye … / I hate the new Kanye, the bad mood Kanye … / And now I look and look around and there's so many Kanyes."

Two years after "Pablo," West released "Ye." The album is the first to feature the artist explicitly talking about his mental health. On the album’s cover, written in bright neon green letters are the words "I hate being / Bi-Polar / its awesome." The album is indelicate at times, especially when the rapper addresses sexual assault accusations against Russell Simmons, and vulnerable other moments, especially when discussing fatherhood and marriage.

West's ninth studio album, "Jesus is King," was released in October 2019 and it is his most overtly religious album, featuring songs like "Follow God," "Use the Gospel" and "Jesus Is Lord." Featured artists include Fred Hammond, Kirk Franklin and West’s own gospel group, Sunday Service Choir.

West is in the process of releasing his 10th studio album, "Donda," named after his late mother. Originally scheduled for release on Apple Music last month, it is expected to premiere Sept. 3.

I am excited to hear what the artist releases, but I will no longer listen uncritically to what writer Clarissa Brooks, after attending the first "Donda" listening event in Atlanta last month, succinctly described in Dazed magazine as the rapper's "anti-Black political views, his deep-seated misogynoir, and his allegiance to idolatry at the hand of white supremacy.”

In recent years, Kanye has publicly described slavery as a choice and supported former President Donald Trump. And during his third listening event in Chicago this week, he invited to the stage fellow rapper DaBaby, who made anti-gay comments last month during a music festival in Miami, and Marilyn Manson, who faces four lawsuits and accusations of sexual assault from at least a dozen women.

What does it mean for fans to love Kanye in the context of today's world? What does this tension tell us about the art we consume and how it relates to misogynoir? Especially within hip-hop, a culture constantly "demanding the silence and dismissal of Black women who have chosen to come forward about their respective traumas," as Shamira Ibrahim writes in Mic? (This week marked the 20th anniversary of the death of R&B star Aaliyah, whose abuse by R. Kelly was enabled or ignored by many in the hip-hop and R&B community.)

This isn't exclusive to Black male creators. Think Shia LaBeouf, Matt Lauer, Luke Walton, Joss Whedon. Think the Catholic Church. How long can we accept misogynoir, racism, sin by the institutions and people we love?

As a female hip-hop fan, I struggle with loving and understanding that my own politics have progressed further left than most of the male rappers who once galvanized and inspired me. I try, and often fail, to make sense of that love and what it means to hold male Black and brown creators accountable when they become reactionaries or fail to unlearn toxic conditioning.

And this isn't exclusive to Black male creators. Think Shia LaBeouf, Matt Lauer, Luke Walton, Joss Whedon. Think the Catholic Church. How long can we accept misogynoir, racism, sin by the institutions and people we love?

For weeks I waited for the release of "Donda" and replayed every one of Kanye's solo albums. In college and well into my 20s, his music and lyrics felt radically ahead of their time. Sonically, his music — even more than a year into a pandemic that has shifted our relationship to the art we consume — challenges the listener to step outward, to think and feel outside ourselves.

Kanye West, or Ye, as he may soon be known, will always be an artist who helped me think about the insidious ways systemic oppression surrounds us, the limits of our consumerist culture, the joys and pains of creating with an audience in mind and how our anxieties can blind us to God's movement around us.

I also see the flaws in his work, and in my own relationship to the culture that shaped me, and I am challenging and learning to develop a love of the genre outside its Black, cisgender heteronormativity.