Inmates perform Jesus Christ Superstar inside the Sarita Colonia prison in Callao, Peru, Tuesday, April 15, 2014. Domestic and foreign prisoners put on the play for an audience of prison authorities during Holy Week for the third year in a row. (AP Photo/Karel Navarro)

On March 25, 1971, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a small, private Lutheran college held an illegal performance of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice's rock opera "Jesus Christ Superstar ." The stripped-down, oratorio-style show was an entirely student-led endeavor featuring a physics major as music director and faculty members donning doctoral robes playing high priests.

"I can't read music, and I'm not a musician," said Larry Recla, the seminary intern who produced and directed the Gettysburg College production. "This thing exploded and took on a life of its own."

Weeks into rehearsal, the company received word of a court order prohibiting amateur companies from performing the show for copyright reasons. Undeterred, the group decided not to print advertisements and to call the performance a dress rehearsal in an effort to avoid a lawsuit. Despite the lack of printed publicity, the performance attracted more than 1,200 audience members, some of whom sat on windowsills or stood outside to catch the sound of drums and electric organ.

Advertisement

"It was explosively glorious," said Recla. "People could not sit still; they were up yelling and screaming. The applause after each of the shows lasted 10-15 minutes."

Months later, on October 12, 1971, a glitzy, over-the-top performance of "Jesus Christ Superstar" opened on Broadway. The critics weren't thrilled — some called it brash, and Webber himself called it vulgar — but thanks to a $1,000,000 advance sale and the attention of religious protesters, the show was already a phenomenon. This month, the show celebrates its 50 anniversary.

Initially, Rice and Webber's idea for a rock opera passion play didn't take off — one investor called it the "worst idea in history," and the 1970 concept album was banned by BBC radio for being sacrilegious. The album met a different fate in the U.S., where it became the bestselling record of 1971.

"For a lot of people, it was the visceral excitement of the music," said Devin McKinney, archivist at Gettysburg College and author of "Jesusmania!: The Bootleg Superstar of Gettysburg College." "It got your body moving and mind thinking and connected it with this religious impulse that a lot of kids felt or wanted to feel."

The original album, with numbers including "I Don't Know How to Love Him" and "Superstar," employed rock-infused Broadway tunes to narrate the week leading up to Jesus' crucifixion, all told from the betraying disciple Judas' perspective. The hit album inspired a slew of amateur performances of the show that preceded the Broadway production.

The album arrived just as Christian rock was beginning to emerge in the U.S. — Norman Greenbaum's "Spirit in the Sky" was a chart-topper in 1970, and the Jesus People's Movement was blending the electric sounds of 1960s-counterculture with evangelicalism. "Jesus Christ Superstar" hit the sweet spot: "This was literally the first time a thoroughly Christian message was coming through rock-and-roll music, the dominant cultural medium for young people at the time," said McKinney.

The Broadway production wasn't as immediately successful as the album. Critics loathed the gaudy production, and Christians bristled at the show's depiction of romance between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, its choice of Judas as narrator and its lack of resurrection. Billy Graham said the show "bordered on blasphemy," and in a 2021 interview, Ted Neeley, the original understudy for the Jesus role on Broadway, said,Every single performance was protested by people calling it sacrilegious. They would try to keep us from going in the stage door."

Even today, the show's biblical blunders have proved too big for some Christians to stomach.

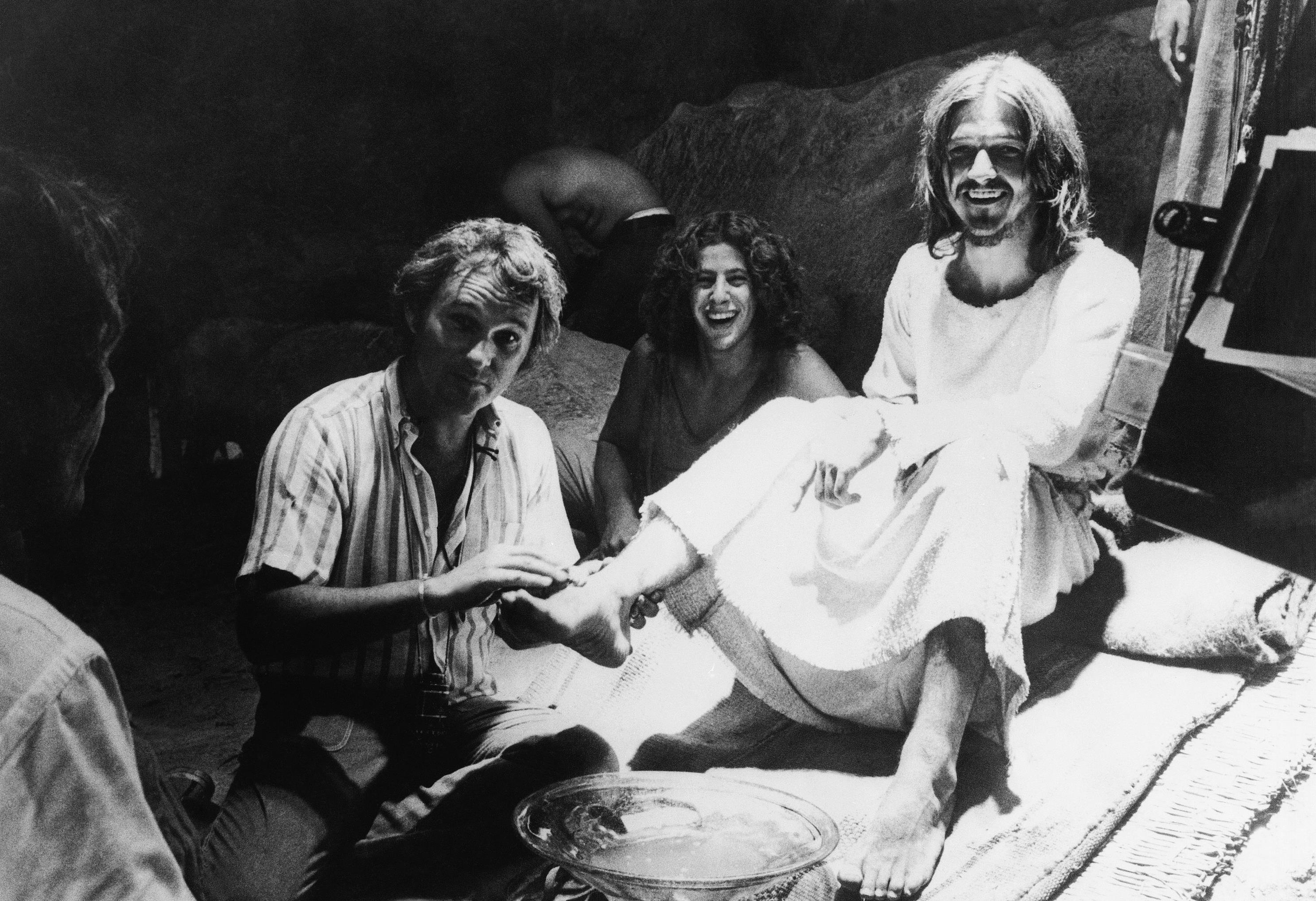

In this Oct. 8, 1972 file photo, producer-director Norman Jewison, left, demonstrates how he wants an actor to wash the feet of Jesus, portrayed by Ted Neeley, during filming of the movie version of the Rock Musical, "Jesus Christ Superstar," in Bethlehem, Israel. (AP Photo, File)

"I mainly love it, but I love it in spite of myself," said Mark Goodacre, professor of religious studies at Duke University. "As a New Testament scholar, I have all sorts of problems with it. But I so love the music. And I also think that a lot of Tim Rice's rather cheesy lyrics occasionally hit that moment of genius."

One sticking point is Rice and Webber's depiction of a human Christ who is overwhelmed by his followers, exhausted from his ministry and unsure what the crucifixion is for. "Show me there's a reason for your wanting me to die, You're far too keen on where and how, but not so hot on why," he sings in "Gethsemane."

Jesus' human nature is further explored in his relationship with Mary Magdalene. In the original Broadway production, the two "fondle and kiss each other," according to a 1971 New York Times review. Subsequent interpretations have taken a more subtle approach, but still, Mary Magdalene's character is largely reduced to her struggle with romantic feelings for Jesus.

"It's one of the most disappointing things about the show in many ways, that it simply buys into the once-popular cliché but complete fallacy that Mary Magdalene is a sex worker," said Goodacre, who noted the ways Rice and Webber conflated Mary Magdalene with other biblical figures such as Mary of Bethany, the woman who anointed Jesus' feet in Luke 7, and the woman caught in adultery in John 8.

Even today, the show’s biblical blunders have proved too big for some Christians to stomach.

Rice and Weber also made the bold move to end the show with the crucifixion. Still, Goodacre said, directors have to decide how to portray Jesus during the curtain call — if he returns in "glorious arrayments" rather than crucifixion garb, the result can be "a sort of resurrection."

While Christians protested over the godlessness of the show, Jewish groups criticized the show's depiction of Jewish high priests, who, in the original production, were dressed as gargoyles. "It's just a few years earlier that the Vatican council finally said explicitly that Jews are not collectively responsible for the death of Jesus," said Henry Bial, chair of the theatre and dance department at the University of Kansas. "To have this high-profile moment where the high priests of Israel are conspiring against Jesus, and they come off pretty craven, you could see why people would get uncomfortable about it."

In interviews, Rice and Webber — both raised Anglican — said they were never trying to make a theological point about Judaism or Christianity. Their goal had been to craft a compelling show.

"People have read so much more into this than we ever intended," said Rice in a 1971 New York Times interview. "We were simply trying to express our feelings about Christ at the time, trying to tell His story and make suggestions for the gaps. We weren't trying to make a comment. Who are we to make a comment?"

Ultimately, the show is more about asking questions than answering them. "Who are you? What have you sacrificed?" Judas asks in the song "Superstar." "Do you think you're what they say you are?"

Fifty years later, the show's impact is difficult to exaggerate. It's been resurrected for arena tours, film, worldwide theatre productions and most recently, the 2018 Live NBC production featuring John Legend and Sarah Bareilles.

Perhaps the show's most lasting legacy is the music itself. "It's given us a whole bunch of extremely memorable songs," said Goodacre. "When I read the New Testament passion, I quite often end up humming tunes from 'Jesus Christ Superstar.'"

Goodacre said the music created a movement that opened up the Christian story to a generation that wouldn't have otherwise gone near it. "It is explicitly non-confessional. It isn't giving you a Christian take on the story, it's deliberately not reverential. I think that makes it very palatable to a broader audience," he said. "They don't feel that they're having the gospel rammed down their throats."

Bial said the show helped pioneer the rock musical genre and that, while it comes in a long line of attempts to stage the Bible, "it is far and away the most commercially successful adaptation of the Bible that we can find really in theatre history." According to Bial, the show also led to technical advancements, including the miniaturization of rock concert equipment for theatre and mic adaptations that allowed singers to be heard over electric instruments.

"It proved that you could make a lot of money on a show that critics don't particularly like," added Bial, who said "Superstar" was one of the first shows to use word of mouth and advance sales to promote the show before it opened. According to Bial, these tactics created enough momentum to launch "Superstar" as one of the first mega musicals — "it became almost a brand in and of itself," he said.

Surprisingly, Recla, the seminarian who staged the bootleg version of "Superstar" at Gettysburg College, isn't a fan of the musical. "I haven't seen any of the other productions, because it's not the same," he said. Instead, he's a devotee to the event that took place 50 years ago in Gettysburg. That iteration, which preceded the Broadway production by seven months, used an entirely different approach, Recla said, that prioritized music over pageantry and staged a resurrection at the show's conclusion.

For Recla, the biggest miracle involved was the show itself. "Being part of the show demonstrated what can happen when people of a variety of differences are of one mind with a mission," said Recla. "It meant that I would, for the rest of my life, believe in miracles."