President Richard Nixon on Nov. 15, 1969, the day of the mass Moratorium march and rally protesting the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C. (PBS/Courtesy of Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum)

Activists, government officials and historians' eyewitness accounts inform "The Movement and the 'Madman,' " a fascinating look at an important chapter in 20th century U.S. history and a celebration of activism's power. The documentary premiered March 28 as an "American Experience" presentation on PBS and is available to stream at PBS.org and on the PBS app.

Former "Leave it To Beaver" child actor Stephen Talbot produces and directs "The Movement." The veteran documentarian may be best known for his "Frontline" documentaries, including 1995's "The Long March of Newt Gingrich." Talbot's latest film explores how Richard Nixon's election as the 37th U.S. president in November 1968 represented a critical turning point in the U.S. government's Vietnam War strategy, which engendered antiwar protesters' corresponding shift in tactics.

As the documentarians note, by 1968 more than 500,000 Americans were fighting in the war, and 31,000 Americans and more than 1 million Vietnamese had been killed. Only 26% of Americans approved of President Lyndon Johnson's handling of the war. Candidate Nixon promised a new course, which, he insisted, would result in "peace with honor."

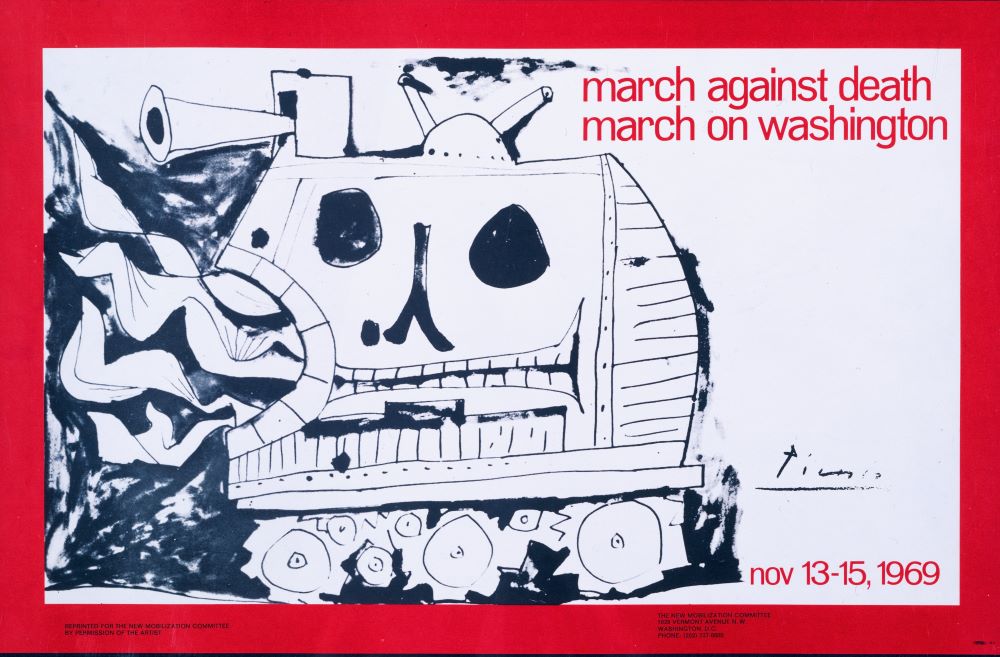

Picasso created this poster for the Nov. 13-15, 1969, antiwar protests. (PBS/Courtesy of Library of Congress)

The documentary opens with footage of a televised campaign town hall event, "The Nixon Answer," where the Republican standard bearer tells the audience: "We should not risk a nuclear war in Vietnam." Once elected, however, working closely with national security adviser Henry Kissinger, the new president brought the nation perilously close to that reality.

According to Kissinger's former aide Morton Halperin, the duo conceived a secret plan to threaten North Vietnam with nuclear weapons, while warning our chief adversary, the Soviet Union. Operating under a "madman theory," Nixon and Kissinger wanted our enemies to fear Nixon was "crazy." Former Defense Department official Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers whistleblower, recalls Nixon's former Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman said Nixon wanted others to know "he has his finger on the nuclear button."

In 1969, the movement was reeling from the ill-fated protests in Chicago during the Democratic Party's national convention in August 1968. Organized by Students for a Democratic Society and the more colorful, provocative and controversial Youth International Party, the protests devolved into violence and chaos. An estimated 15,000 Illinois National Guard and U.S. Army troops and 12,000 city police forces beat protesters with batons and dispersed crowds with mace and tear gas.

In what the federally appointed Walker Commission characterized as a "police riot," more than 100 police officers and 1,000 civilians were injured during the mayhem. Despite the condemnation of the police, a Harris Poll found 66% of Americans approved of how Chicago Mayor Bill Daley employed the city's police against the demonstrators.

Young staffers talk in the Washington, D.C., office of the Oct. 15, 1969, Moratorium march. Staffers include co-organizers David Hawk (seated) and Sam Brown (far right, wearing tie). (PBS/Courtesy of Library of Congress)

The National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, a coalition of groups opposed to U.S. involvement in Vietnam, called for national protests Oct. 15 and Nov. 15, promoting a moratorium for the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the Asian nation. Meanwhile, in a Sept. 26, 1969, press conference, the president stated: "Under no circumstances will I be affected by it (antiwar protests.)" Despite this public declaration, Amherst University historian Christian Appy says, Nixon "was deeply obsessed with the antiwar movement."

The documentary follows the success of the October 1969 moratorium events in achieving the organizers' aims of peaceful protest and mainstream diversity. As one commentator says over a wonderful tapestry of archival video and still photos — including one of the director himself —from Cincinnati to New Orleans to Palo Alto, up to 3 million people from all walks of life participated in protests in 200 cities. Except for some late afternoon skirmishes in Washington, the protests remained largely peaceful and the country, as Ellsberg says, "avoided the first nuclear test since Nagasaki."

The protests — including the largest protest crowd until that point on Washington's National Mall — steered the president away from that disastrous course. Having abandoned Operation Duck Hook, (a golf term for an errant pulled shot) as his secret pressure campaign was dubbed, President Nixon ordered the Air Force to maintain a nuclear weapons alert between the October and November moratoria.

Advertisement

Watching the images of the impressive throngs united in common purpose, some viewers may grow wistful and pensive reflecting upon a country that no longer exists. But in several respects, "The Movement" speaks to our distressing Trumpian era. The madman theory certainly applies to the former president, who said North Korea would be "met with fire and fury and frankly power, the likes of which this world has never seen before."

He also speculated about nuking hurricanes to deter them, and he wanted to bomb Mexican drug cartels. In 1968, as demonstrators carrying candles passed the White House, Nixon speculated: "Can’t we get some helicopters to fly over and blow out the candles?" Similarly, during the 2020 George Floyd protests, the Trump administration used low-flying helicopters to disperse protesters. The resemblance is hard to deny.

Its timeless message about activism's value ultimately recommends "The Movement and the 'Madman'" to audiences with an interest in history and social change. Viewers who have been part of a social movement will recognize themselves in these determined and resilient protesters, who would only far later discover how their actions avoided nuclear disaster.