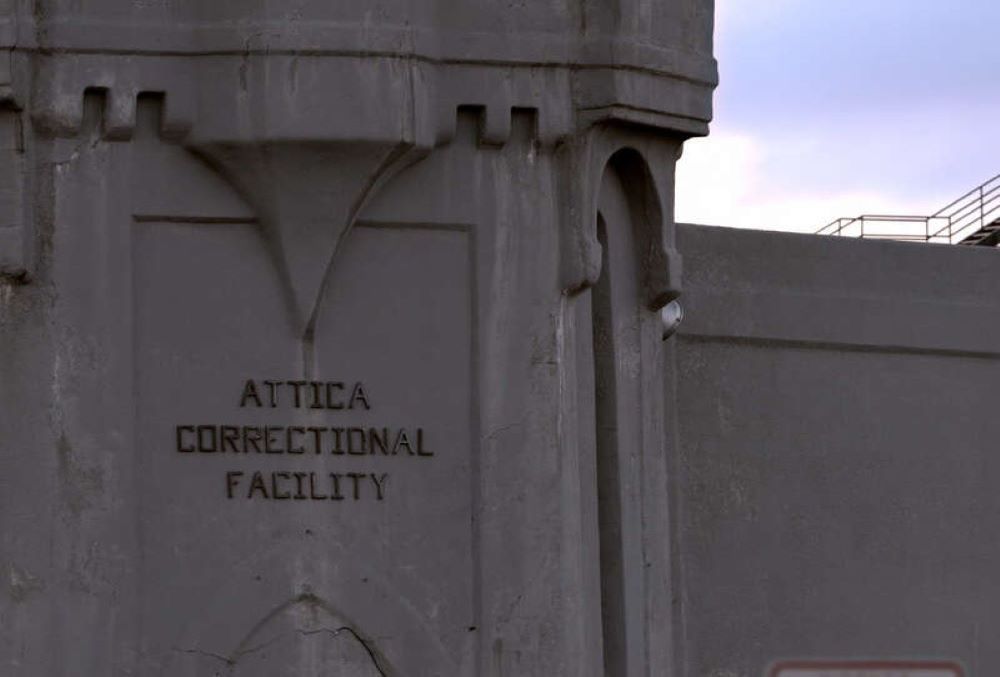

Showtime's documentary "Attica" premiered Nov. 6. (Showtime)

"Attica! Attica! Attica!" bank robber Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino) chants, defying NYPD officers' attempts to negotiate the release of the hostages Sonny holds inside a Brooklyn bank.

This often cited pop culture moment from the late Sidney Lumet's 1975 Academy Award winning film "Dog Day Afternoon" may be the only remote connection many Americans have to the largest, bloodiest prisoner rebellion in U.S. history: Sept. 9-13, 1971, in upstate New York’s Attica Correctional Facility.

Viewers of the meticulously shaped, immersive "Attica" will no longer regard what happened in the prison 50 years ago as some ancient riot. Rather, the tragic state assault that gratuitously ended 39 lives in the raid will remain seared in viewers' consciousness.

The documentary, which premiered on Nov. 6, is available on Showtime, and it is Stanley Nelson's ('Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool') 26th film in his more than three-decade career. The African American documentarian received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama in 2013.

The co-director is Traci A. Curry, who also collaborated with Nelson as a producer on 2019's "Boss: The Black Experience." This is her first director's credit.

The day-by-day account of the prison uprising begins Thursday, Sept. 9, when roughly 1,300 of the 2,000 inmates — two-thirds of its population — took 42 guards as hostages and seized control of the prison's D Yard.

Much of the archival footage in Showtime's "Attica" is previously unseen New York State Police surveillance video. (Showtime)

As the uprising grew excessively violent, the New York State Police and Attica correctional officers reassert control over the prisoners on Monday, Sept. 13, which concludes the documentarians' reckoning.

Nelson and Curry admirably let all impacted groups have their say about what happened: former prisoners, the hostages' family members, persons asked by the inmates to be observers and national guard members asked to assist with the injured and dead after the state re-assumed control of the prison.

An altercation between the guard and an inmate ostensibly precipitated the prisoner rebellion. For others, this revolt was ineluctable. As former prisoner George Che Nieves says, "something was always ready to happen at Attica. The population was tired, tired of the lies, tired of promises."

LD Barkley, a 21-year-old African American Rochester, New York, native with mere days left on a 90-day sentence for a parole violation, emerged as the inmates' articulate spokesperson on that first day. (Barkley died in the police attack.)

The prisoner revolt didn't result from enmity between the guards and inmates, but, Barkley said, from "unmitigated oppression brought by the racist administrative network of this prison throughout the years."

"We are men," he said. "We are not beasts and we do not intend to be beaten or driven as such." They wanted assurances from Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller they would face no reprisals for their rebellion and the media would report their cause.

Invited to become an observer of the prisoners' struggle, Herman Schwartz, then SUNY Buffalo law professor, understood immediately what increased media attention meant for the inmates. The 89-year-old constitutional law scholar says, "now the prisoners had a worldwide audience."

Advertisement

As the uprising grew excessively violent, the New York State Police and Attica correctional officers reassert control over the prisoners on Monday, Sept. 13, which concludes the documentarians' reckoning.

Nelson and Curry admirably let all impacted groups have their say about what happened: former prisoners, the hostages' family members, persons asked by the inmates to be observers and national guard members asked to assist with the injured and dead after the state re-assumed control of the prison.

An altercation between the guard and an inmate ostensibly precipitated the prisoner rebellion. For others, this revolt was ineluctable. As former prisoner George Che Nieves says, "something was always ready to happen at Attica. The population was tired, tired of the lies, tired of promises."

LD Barkley, a 21-year-old African American Rochester, New York, native with mere days left on a 90-day sentence for a parole violation, emerged as the inmates' articulate spokesperson on that first day. (Barkley died in the police attack.)

The prisoner revolt didn't result from enmity between the guards and inmates, but, Barkley said, from "unmitigated oppression brought by the racist administrative network of this prison throughout the years."

"We are men," he said. "We are not beasts and we do not intend to be beaten or driven as such." They wanted assurances from Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller they would face no reprisals for their rebellion and the media would report their cause.

Invited to become an observer of the prisoners' struggle, Herman Schwartz, then SUNY Buffalo law professor, understood immediately what increased media attention meant for the inmates. The 89-year-old constitutional law scholar says, "now the prisoners had a worldwide audience."

Other notable observers included the late New York Times journalist Tom Wicker (“A Time to Die: The Attica Prison Revolt”), deceased, fabled civil liberties attorney William Kunstler and 90-year-old, longtime counselor to Dr. Martin Luther King, the estimable Clarence Jones.

Summoned to observe, these religious leaders, attorneys and reporters attempted to mediate a resolution to inmate demands with New York Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald. The commissioner agreed to most prisoners' basic demands for, as Schwartz says, "medical care, decent food, fair disciplinary hearings," among other things. Another observer, former ABC reporter John Johnson, felt hopeful the impasse could be "negotiated to a decent humanitarian end."

The governor, however, wouldn't accede to the prisoners' insistence upon clemency. When 28-year-old guard William Quinn, badly beaten in the takeover, died two days later, the inmates lost much of their negotiating leverage.

By 10 o’clock the morning of the 13th, the state had retaken Attica.

"Attica" works on intimate, personal and big-picture levels.

The moment Charles Horatio Crowley, also known as Brother Flip, addresses the observers will indelibly affect viewers. "If we cannot live as people," he says, "then we will at least try to die like men."

Much of "Attica's" power, however, derives from the way its previously unseen archival footage puts you in the thick of the state's stunning, horrifying, devastating military-style assault upon the prisoners and the hostages.

Much of this footage is New York State Police surveillance video, which the filmmakers use against the state to indict it.

The grainy black and white images create an unsettling fog of war as menacing helicopters hover, tear gas rains down and some officers employ unjacketed bullets against their victims. This ammunition was banned by the Geneva Conventions because of the severe harm they cause.

After the 20-minute attack is over, their captors force the inmates to crawl, "like a dog" in former prisoner Al Hajii's memorable phrase, naked through excrement, and beat and torture them.

"Attica" isn't easy to watch. Other than the brutality, the images of full-frontal male nudity may discomfit some. But these images, make the entirely appropriate, important connection, as one commentator suggests, to African Americans and slavery.

Viewers will marvel at the ex-offenders' resiliency as they contend with the fresh and palpable memories of the degradation they endured half a century ago.

Viewers willing to confront "Attica's" stark realities will agree with Clarence Jones. At the time of the film interview, he said, "God willing in a few months, I'll be 90 years old. I'll never ever, ever, ever forget Attica."