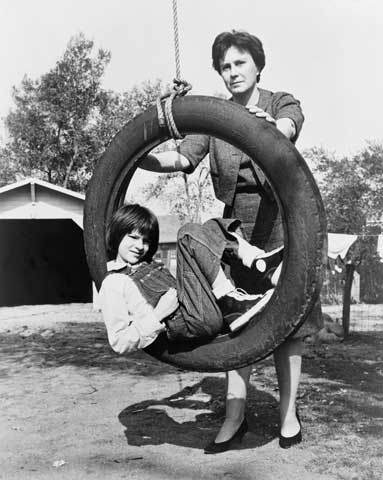

Harper Lee with child actress Mary Badham, who starred in the 1961 film "To Kill a Mockingbird" (Newscom/Everett Collection)

Editor's note: Harper Lee died Feb. 19. As a tribute to Lee, we are promoting a column from our April 10-23, 2015, issue, written by Colman McCarthy about his encounter with the author.

Whenever it's published in the next few months, I expect to read Harper Lee's novel Go Set a Watchman. The 304-page book, said to be a sequel of To Kill a Mockingbird, the everlasting 1960 classic, was recently discovered in the author's archives.

The flare of publicity that brightened the literary world when the long-lost manuscript was found brought to mind the May 11, 1997, afternoon in which I enjoyed Lee's company. The scene was the graduation ceremony at Spring Hill College, the Jesuit liberal arts school in Mobile, Ala. I was on hand as the commencement speaker and recipient of an honorary degree. The other honoree -- a Doctor of Humane Letters -- was Lee.

Before the ceremony, in the wardrobe room where deans and professors were attiring themselves in academic regalia, I suggested to the college president that it would be fine with me, and far more memorable for the graduates, if Lee, luminous and truly worthy, gave the speech.

No, she had been asked but declined. Merely to have her there for the honorary degree was seen by the Jesuit fathers as a large feather in the college's cap -- a bit of plumage hard to go unhailed.

It was rare for Lee to leave the comforts and confines of her nearby village, Monroeville, for any enticement. Though not as adamantly self-cloistered as the eremitic J.D. Salinger, her ranking as one of literature's leading homebodies was secure. The Associated Press reported that the Spring Hill "appearance was not publicized and the reclusive author did not submit to any interviews, but Harper Lee graciously -- and quietly -- accepted an honorary degree and a standing ovation. ... Miss Lee glanced from side to side, her eyes wide with surprise, as the crowd stood and applauded her Sunday. She has spent nearly four decades avoiding this kind of adoration."

As we walked together in the outdoor procession along the college's Avenue of the Oaks to the stage, I seized the chance for a conversation. Keeping it light but still above a banter, we told each other of our trips to the campus -- mine from Washington, hers from Monroeville.

Then my question: Are you writing much these days? Yes, Lee said, a lot of writing.

I wasn't expecting that. What kind of writing, I wondered. Had I missed a story she had written for The New Yorker? A review of her last book in The Times Literary Supplement?

Trying not to be pushy, but still hoping for a specific or two, I asked: "What sort of writing?"

It was letters, she said, letters to schoolchildren who wrote to offer their thoughts about the novel, how inspired they were by Atticus Finch.

I could only guess the number of letters Lee had written since To Kill a Mockingbird had appeared in 1960. I could only guess, too, how much the letters meant to the children who received them.

I was touched by Lee's fidelity to her craft, even if it was writing not meant for publication and much less for acclaim. And it moved me to regret the many times I had received letters from schoolchildren about columns I had written, or from former students in my classes, and I pushed them aside unanswered: They're just kids, don't waste time on them.

My debt to Lee and her example of graciousness is that since that sunny Alabama afternoon in 1997, I have answered every letter I've received from children -- no matter the time it took, no matter the topic.

One question I didn't ask Lee was why she accepted the invitation to Spring Hill. My hunch is that she admired the Jesuit fathers' singular embracing of racial equality, having enrolled black students in the early 1950s. In the four years I was an undergraduate at the college, 1956-60, the Ku Klux Klan regularly caravanned through the campus, enrobed and hooded in white, attempting to terrify black students.

Because of its brave stand, Spring Hill earned a footnote in the history of the American civil rights movement: It was singled out for praise by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., in his "Letter From a Birmingham Jail." It was the only school he mentioned, much the same as Spring Hill's was the only honorary Jesuit degree Harper Lee ever accepted.

[Colman McCarthy is the director of the Center for Teaching Peace, a Washington nonprofit. His new book is Teaching Peace: Students Exchange Letters With Their Teacher.]