Before Mass on July 23, 2017, parishioners of Christ the King Catholic Church planted 44 crosses on the church lawn to commemorate those who had died 50 years before in the Detroit riots. (Don Hanchon)

A major Hollywood film, a play, several documentaries, three museum exhibits and a host of public forums mark the 50th anniversary of the 1967 civil disorder in Detroit this summer. The five days of violence, looting and arson left 43 people dead, 342 injured and large swaths of one of America's greatest cities in smoldering ruins.

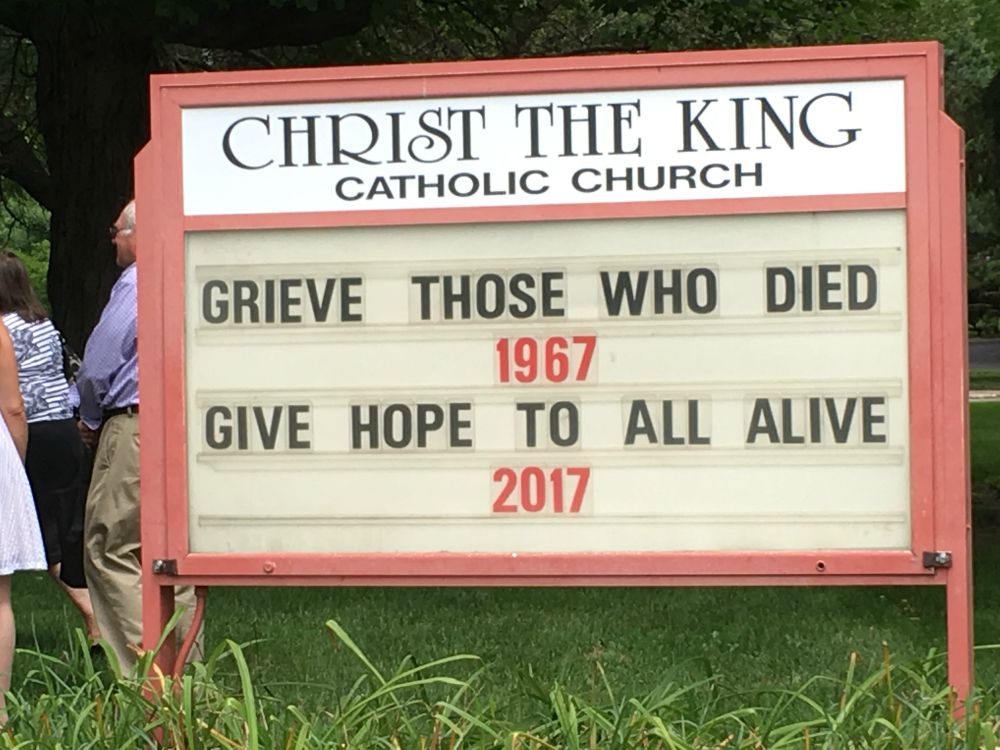

It all began on a Sunday morning, and Catholics across Detroit marked the day on another Sunday a half century later. Before Mass on July 23, 2017, parishioners of Christ the King Catholic Church, for example, planted 44 crosses on the church lawn to commemorate those who had died 50 years before. (The official number is 43 dead, but the parish found an additional name on lists of victims.)

In the wake of the devastation of 1967, Detroit Archbishop John Dearden directed all archdiocesan priests to preach on the Sunday following the violence about the need to rebuild the city "in a spirit of Christ-like love and concern." Dearden continued pressing the need for the church in the U.S. "to become the moral voice of the whole community" on civil rights issues.

On Palm Sunday 1968, just days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Dearden announced the diversion of $1 million from the annual Archdiocesan Development Fund (ADF) away from Catholic programs to other anti-poverty programs that were nonreligious.

Rev. Victor Clore, writing about 1967 in three essays this July for the Christ the King parish bulletin, The Broadcast, said Dearden's program was "so successful that the United States Catholic Bishops adopted the same model — the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. Since 1970 the CCHD has contributed over $300 million to more than 8,000 low-income-led, community-based projects that strengthen families, create jobs, build affordable housing, fight crime, and improve schools and neighborhoods."

At the time, Dearden was president of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops and led the development of the CCHD, according to a history of the organization.

Advertisement

According to Clore, Dearden's other significant decision was to permit two priests then teaching at Sacred Heart Seminary who wanted to train a cadre of select priests to preach effectively about racism to white Catholics across the archdiocese. They called their project, begun in March 1968, "Focus: Summer Hope." The goal: preventing a repeat of the violence that summer. Later, as their mission and vision grew, they simplified it to "Focus: HOPE."

Dearden could not have known that the work of Frs. William Cunningham and Jerry Fraser would evolve into a multi-million-dollar non-profit agency that left an indelible stamp on a city desperately in need of creative and practical ideas to help disadvantaged people climb out of poverty and into the middle class. Fraser left Focus: HOPE early on, but Cunningham and Eleanor Josaitis, a Catholic mother of five, would commit themselves to developing practical ideas to bring blacks and whites together while creating educational and career opportunities for the underprivileged.

During the civil unrest in Detroit in July 1967, someone used black paint to alter the face, hands and feet of the statue of Jesus that stood outside Sacred Heart Seminary. When someone else repainted the statue back to white, the seminary's rector, Monsignor Francis Canfield, and two seminarians repainted it black in a gesture of solidarity. (Tom Diggs)

Cunningham, then age 38, was a charming man with a quick wit and a passion for civil rights. From his second-floor window at Sacred Heart, just blocks from the epicenter of the violence, Cunningham could see, smell and hear the destruction of those hot days in 1967. He vowed to devote his life to overcoming the despair enveloping the city he loved.

The riot — that many now call a "rebellion" against racial oppression — "uncorked me," Cunningham would later say. "At that moment, [the seminary] seemed so completely irrelevant and so awesomely removed from real life. Fifty-caliber machine guns taking down sides of apartment buildings! Bloody bodies out in the street, and America's arsenal encamped at Central High School and choppers overhead! And, here I am looking out of the window of my apartment, a very academic apartment — a book reviewer, I was — and saying to myself, 'How can you go back to what you're doing?' "

Building from the parish

Dearden grew frustrated that Cunningham had quit the seminary faculty and wanted to work full time on Focus: HOPE. Cunningham also refused to let the organization fall under archdiocesan control. Finally in 1970, Dearden allowed the priest to run the now-secular Focus: HOPE. Cunningham agreed to be temporary pastor at a struggling parish in the city's industrial north end, the Church of the Madonna, which Dearden had planned to close.

Instead, Cunningham breathed new life into the parish and used its rectory as a base to build Focus: HOPE into an agency with a unique portfolio of programs serving the poor and an annual budget in the early 1990s of more than $80 million, most of it federal funds.

Christ the King Catholic Church held a memorial July 23, 2017, which Auxiliary Bishop Don Hanchon attended. Hanchon was a seminarian and living at St. Agnes Parish, about four blocks from where the 1967 riots began. (Don Hanchon)

In the 1970s, Cunningham and Josaitis joined forces with Fr. Roger Morin of New Orleans (now retired bishop of Biloxi, Mississippi) to lobby Congress and the Nixon administration to pay non-profit organizations to distribute tons of stockpiled food commodities like peanut butter and dried milk to impoverished children and their mothers. The three worked for years to get the U.S Department of Agriculture to include baby formula and to expand the program to low-income seniors.

The USDA's Commodity Supplemental Food Program continues to provide nutritious food to thousands of low-income seniors across the country.

In 1981, when an aging factory across the street from Madonna Church went up for sale, Cunningham envisioned a training program for skilled machinists, then in short supply. With help from U.S. Senator Carl Levin, D-Michigan, who served on the Senate Committee on Armed Services, the Pentagon loaned hundreds of lathes, drill presses and other machine-tooling equipment that had been stored in limestone caves since World War II. This allowed Focus: HOPE's faculty of mostly retired machinists to provide hands-on training.

A few years later, Cunningham and Josaitis brought a new idea to the federal government — a cutting-edge manufacturing and training center for engineers using computer-guided machinery that opened in 1993. To raise the millions needed for this Center for Advanced Technologies, they convinced the heads of four federal departments — Defense, Education, Labor and Commerce — to sign a single memorandum of understanding. The Pentagon alone provided $100 million over 10 years to build the center.

The Department of Defense funding rubbed many Catholics the wrong way, including fellow clergyman Thomas Gumbleton, auxiliary bishop of Detroit and a well-known peace activist. "It's called beating swords into plowshares," Cunningham responded. "I'm pulling it out of a budget that would normally be used to build weapons for defense or killing."

George H.W. Bush visited Focus: HOPE when he was vice president and supported its development in Washington through his own presidency. In 1994, President Bill Clinton toured the Center for Advanced Technologies while in Detroit for a G-7 meeting of international business leaders. By then, Focus: HOPE was operating several programs in five former factories on a large campus taking up three city blocks.

"Instead of saying 'if,' this is a place that says 'when,' " Clinton said of Focus: HOPE. "This model here could be seen sweeping across America if we had the kind of local leadership that is manifest here by the stunning examples of Cunningham and Eleanor Josaitis. I have never been in a place as advanced, as upbeat, as hopeful as this place."

People contemplate the altar at Christ the King Catholic Church on July 23, 2017, to mark the anniversary of the Detroit riots that killed more than 40 people. (Don Hanchon)

Cunningham was the most high-profile Catholic cleric in Detroit working to overcome the sins of white racism. But hundreds of priests, nuns, seminarians and lay people also responded to the disaster of 1967.

"What I saw was the Catholic Church out in the community," said Isaiah McKinnon who was one of the few black police officers in Detroit during the rioting. "They sent seminarians out into the community to treat people to heal the wounds and despair throughout the years," said McKinnon, a Catholic who served as the city's chief of police from 1994 to 1998 and deputy mayor from 2013 to 2016.

Clore said that the 1967 "insurrection exploded from decades of institutional racism and segregation. The 'white flight' that was already underway in Detroit was whipped into a frenzied stampede." Although Dearden and succeeding prelates in Detroit continued devoting resources to help the poor, the archdiocese over the decades would also close dozens of parishes and schools as congregations dwindled.

"Church is about more than praying, paying and obeying," Clore said. "It is also about organizing communities."

Cunningham died of complications from diabetes and cancer in 1997 and Josaitis became executive director. She died of cancer in 2011. Focus: HOPE lives on.

[A former reporter for the Detroit Free Press, Jack Kresnak is the author of Hope for the City: A Catholic priest, a suburban housewife and their desperate effort to save Detroit.]