Melanie Rodriguez, a 51-year-old artist and former teacher, stands in her new tiny home at Kenton Women's Village in Portland, Oregon, in fall 2022. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

As it drizzled outside, Melanie Rodriguez methodically organized her few belongings inside a small white house with yellow trim and a front porch. She hung a purse on a hook, arranged paintbrushes on a desk, placed feminine hygiene products inside a cabinet.

"Tiny homes are PTSD salve," said the 51-year-old. "Here there is privacy and quiet and safety."

A native of the Bronx, New York, Rodriguez was an artist and educator before fleeing domestic violence and subsequently experiencing homelessness. She has spent long stretches on the streets and in shelters.

"I've witnessed the sorrows of many women along the way," she said, sliding a pair of shoes onto a shelf and wiping away tears. "I am strong; I come from tough people. But I fall apart for other women."

Rodriguez is one of the newest residents of Kenton Women's Village, a community with tiny homes, or "pods," for homeless women in Portland. Funded by the Joint Office of Homeless Services (a shared venture between the city of Portland and Multnomah County), the transitional shelter is managed by Catholic Charities of Oregon.

A dearth of affordable housing, stagnant wages and the economic aftermath of the pandemic have led to an increase in homelessness, especially in West Coast cities, and tiny dwellings have become increasingly popular as shelters and transitional housing. A number of local Catholic service agencies, including St. Vincent de Paul and Catholic Charities, have started to manage a broad range of tiny home communities.

The micro-residences span from one-room units, like those at Kenton, to miniature houses with a bathroom and kitchen. Shelters often are built with prefabricated components, while a few are individually designed. Most villages have communal elements and include a range of services. Nearly all the Catholic agencies run tiny home villages with electricity.

Kenton has 17 tiny homes, a community center and shared kitchen and laundry facilities. In tiny home villages "there's this combination of being in your own unit where there's some self-sufficiency, while at the same time being part of a community before you're immediately in your own place," said Todd Ferry. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

There are concerns about the concept, but proponents maintain the tiny home villages are relatively fast to build, appeal to people who eschew traditional dorm-style shelters and — most important — simultaneously provide individuals with community and a door that locks.

"It's amazing to see when someone is safe, warm, valued and not worried about their stuff getting stolen," said Gabe Ash, program director with Catholic Community Services of Western Washington, which staffs a tiny home village in Olympia.

"In this village they can begin to heal," Ash said. "And then, slowly, they can start thinking about what comes next."

Crisis and creativity

Blocks away from where Rodriguez settled into her new tiny house was a sight now omnipresent in the city — a long strip of sidewalk filled with tents, tarp-covered cars and other makeshift shelters, all dripping from the rain.

Portland is among the West Coast cities seeing the biggest increase in homelessness (on Nov. 3, city leaders approved a controversial plan to ban unsanctioned camping), yet it's also home to creative approaches to aiding the unhoused.

Todd Ferry is co-founder of the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative at Portland State University. He helped design Kenton Women's Village and has studied tiny home villages.

When Portland first declared a state of emergency on homelessness seven years ago, "people were saying let's get warehouses with cots for people," Ferry recalled. "Homeless folks, though, said, 'No, we want what we've been trying to get for years, another Dignity Village.' "

'In this village they can begin to heal. And then, slowly, they can start thinking about what comes next.'

—Gabe Ash

In 2000, Dignity Village was founded as one of the first pod villages for the unhoused in the country, and it remains the longest running. Like several subsequent Portland villages, it is self-governed.

With elements from Dignity and other villages, Kenton opened in 2017 as the first Portland village funded by the city and county. It has been operated by Catholic Charities of Oregon from the start.

Rose Bak, chief program officer of Catholic Charities, said that homeless individuals, especially women, had been telling the nonprofit for years why they didn't like traditional shelters.

"For what it costs to run 20- or 30-unit villages you could run a giant traditional shelter with 150 beds," said Bak. But the villages can serve those unable to stay in a congregate shelter due to having pets, partners, or intense psychological or emotional issues.

"People also said they didn't feel safe at shelters, people stole their stuff when they went to the bathroom, or people were really loud and that triggered anxiety," Bak said. "It became really apparent to us that a level of privacy with the tiny home model could make a huge difference."

Affordable housing deficit

Although the concept existed for years, the idea of using tiny homes for unhoused people started to gain traction five to 10 years ago, according to Donald Whitehead Jr., executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless.

"We've seen more and more people making homes on the sidewalks of this country, so there's been a sense of desperation to come up with options," he said.

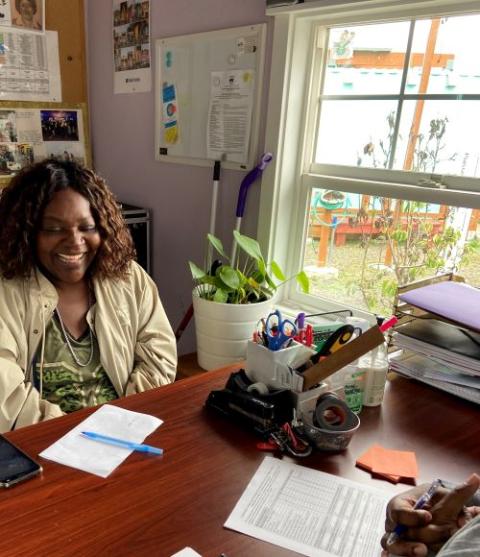

Chiquita Pulliam laughs during a meeting with Courtney Hamilton, manager of homeless services for Catholic Charities of Oregon, at Kenton Women's Village in late October. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

A 2022 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition indicates that every state lacks an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for its lowest-income renters. Likely to exacerbate the problem: Pandemic government relief programs, including anti-eviction measures, are ending.

"I'm supportive of tiny homes as an emergency solution because we have a major homelessness crisis," said Whitehead, adding that long-term solutions are needed, like funding housing vouchers and increasing the quantity of living-wage jobs.

"Tiny homes are a creative, temporary solution to the nationwide crisis of affordable housing, one that cries out for bold policy solutions," added Dominican Sr. Donna Markham, president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA.

Steve Berg, vice president of programs and policy for the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said he thinks the non-congregate model is worth considering but that temporary housing projects, unfortunately, can divert funds from permanent housing initiatives.

"In a lot of places, both models count for spending on the homeless, so they compete against each other for funding," he said. "We need to be doing both but there's not enough money for both."

Los Guilicos Village, operated by St. Vincent de Paul district council of Sonoma County, California, includes communal grills and eating areas. It also has a dog run. (Courtesy of St. Vincent de Paul district council of Sonoma County)

Diverse communities

Tiny home villages and the units themselves vary drastically, and that's reflected in the five Catholic-run initiatives examined by NCR.

At the entrance of Kenton is a small rock garden, where painted stones are covered with words such as "compassion," "perseverance" and "peace." Strands of white lights loop from house to house, and several garden beds, dormant in the fall, stand near the center of the 17-unit community.

Meanwhile at Tampa Hope, run by Catholic Charities of the Diocese of St. Petersburg, Florida, plans call for a total of 300 people living in a mix of tents and tiny homes, with dwellings arranged on a large concrete lot.

In Flint, Michigan, Catholic Charities of Shiawassee and Genesee Counties is planning a 26-house community for veterans, who will reside for five years in 400-square-foot homes, each with a two-burner stove and bathroom.

"I'd love to tell veterans, 'This is yours. Take off your backpack, get settled. This is your home,' " said Vicky Schultz, CEO of Catholic Charities of Shiawassee and Genesee counties.

The goal at Tampa Hope is to secure permanent housing in 60 to 90 days, and homes are 64-square-foot, aluminum-frame Pallet shelters made to withstand a Category 5 hurricane. (The Washington-based company Pallet has boomed during the pandemic.)

Los Guilicos Village, managed by St. Vincent de Paul district council of Sonoma County, California, has 60 Pallet units and the average stay is eight months, while Quince Street Village in Olympia will have some 90 units and no limits on how long people can stay.

The communities run by the Catholic social service providers also share a number of key elements. Often partnering with other agencies, the villages include wraparound services such as counseling, addiction treatment, basic medical care and financial education. And they focus on helping residents secure permanent housing.

Vacant properties are prevalent in Flint, and Schultz hopes to work with neighborhood groups and Habitat for Humanity to rehabilitate homes for the veterans.

Building codes and zoning regulations have been a hurdle for the veterans' village project. "Flint has never had anything like this before, so you are bounced back and forth about ordinances and codes," said Schultz. She hopes to welcome the first residents this spring.

Each of the five communities has shared facilities — restrooms and showers, laundry facilities, and in some cases a community center, dining area or a garden. Los Guilicos Village even has a dog run.

"I've heard anecdotally from folks who've gone straight from the street to affordable housing that it can feel isolating," said Ferry. In tiny home villages "there's this combination of being in your own unit where there's some self-sufficiency, while at the same time being part of a community before you're immediately in your own place."

Lindsay Kendall, village manager, gives a tour of the community center at Kenton Women's Village. Funded by the Joint Office of Homeless Services, the transitional shelter is managed by Catholic Charities of Oregon. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

Dignity for residents

Quince Street Village, like many tiny home communities, emerged from a local crisis. In 2018, 30 tents in the capital city of Olympia grew to more than 300 in a matter of months.

In response, the city established a formal tent encampment on the edge of the downtown historic district and asked Catholic Community Services of Western Washington and other agencies to help care for the population.

"There were days our staff would be brushing snow off the tents so they wouldn’t collapse," recalled Ash, with Catholic Community Services.

The city eventually purchased a new property that's now home to Quince Street Village, and Catholic Community Services manages and staffs the site.

This model was deemed the best option "because we couldn't build permanent supportive housing fast enough to address the need that exploded in our community," Ash said.

Some tiny home villages initially face a NIMBY response from neighbors, but a report earlier this year from the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative concludes that neighbors who live next to these communities grow less concerned over time. At Kenton, members of a nearby Catholic parish regularly bring meals and organize holiday celebrations, and parishioners at St. Michael Church in Olympia intend to support Quince Street Village.

Ash said he's witnessed dramatic turnarounds in village residents. He recalled one woman who'd been living with an untreated mental illness and would shatter glass on the ground. "Recently we helped move her into permanent supportive housing, and now she's involved in trying to help others," said Ash.

"I've been working in this field for a while, and I couldn’t have imagined someone would have a change that big."

He also recalled how after one man moved into his tiny house, he was able to flip on his own light switch for the first time in 20 years.

Residents of Tampa Hope in Florida enjoy a meal donated by a local restaurant. Catholic Charities of the Diocese of St. Petersburg operates the community and will provide a mix of tents and small shelters for residents. (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of the Diocese of St. Petersburg)

The Catholic Church teaches "that we should strive through compassion and the works of mercy to honor the dignity of others," said Jack Tibbetts, executive director of St. Vincent de Paul in Sonoma County. "I think this model really supports that in many ways."

In the recent report on tiny home villages by the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative, villages are defined in part as places where residents have some agency over their environment and there's a sense of community with shared agreements on behavior.

Ferry, the collaborative's co-founder, said he's concerned that some organizations and municipalities have borrowed the look of a tiny home village "and have not brought in other critical pieces that take them from being simply shelters to places where people are engaged in the community and can really thrive."

He said in some cases "the design could use a little more care and thought."

Berg, with the National Alliance to End Homelessness, added that before designing a tiny house community, it's crucial to seek the views of unhoused individuals. "Too often housing and shelters are created without considering the people with a lived experience of homelessness," he said.

Advertisement

Unhoused people were part of the planning process at some, but not all, of the Catholic-run programs, and their residents have — to varying degrees — a voice in how they operate.

Some critics say the new communities of tiny dwellings could become shantytowns, where homeless individuals are relegated to inadequate housing units.

Catholic agency leaders dispute that view when it comes to the villages they manage. "The unsanctioned encampments in our community with no running water, no services and no connection to the broader community already exist and more closely resemble shantytowns," Ash said.

"Bringing people out of those situations and into a dignified shelter that provides warmth, healthy water, a code of conduct, connection to the community and services helps move people out of isolation and poverty and toward connectedness, health, safety and growth."

Bak said that one of the most important things women at Kenton gain is empowerment. "So many have become homeless due to domestic violence or other sorts of trauma, and it's amazing to see them start feeling safer, explore their interests and then see their empowerment," she said.

After Rodriguez finished organizing her belongings in her Kenton tiny home, she stepped outside to her front porch. "I have a house," she said. "Life is good."