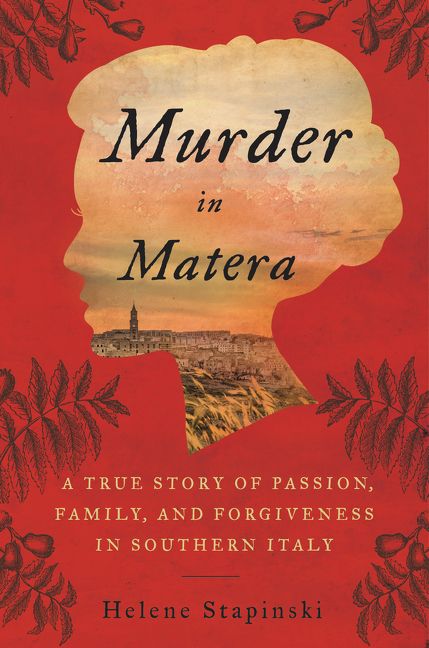

A view of cave churches in Matera, Italy (Wikimedia Commons/Mattis)

"Trinis" do not tell people that the island's name is an historical hoax, Krystal Sital writes. Christopher Columbus intended to "baptize" the next land he discovered, La Trinidad, as in Father, Son and Holy Ghost, in a nod to Ferdinand and Isabella, who had commissioned his voyage, and to the Spanish Catholic Church, under whose auspices he sailed purportedly to convert the savages.

Incidentally, he didn't convert them. He enslaved them. And the three hills, visible as Columbus first spotted the island in 1498, were a coincidence or a miracle, Sital writes. "It depends on how you tell the story."

In her debut memoir, Secrets We Kept: Three Women of Trinidad, Sital tells a tale of racial injustice as it cuts through the fabric of her family. Her story begins as the Spanish, and later the British, enslaved the Amerindians and brought Africans to work the fertile fields of the island. Still later, when people from the British colony of East India came as indentured servants, they gained their freedom, purchased land and continued the pattern of racism.

After her grandfather died, Sital heard conflicting stories about his beating his family without mercy. She interviewed her mother and grandmother to learn the truth. She gathered their remembrances and shares them in the book's early sections. In the last section, she ties everything together with her own recollections.

As Sital teases out a narrative of race relations and gender inequality in Trinidad, Shiva, her grandfather, an elderly Hindu landowner, is the locus of the story. Her mother and grandmother remember him as a monster who beat his wife so severely that she had four miscarriages.

Sital remembers her grandfather's smile as he read to her and bought her ice cream when she was a little girl. He proudly drove her with him in his Jeep while checking on his laborers at the family plantation in Trinidad. She recalls one especially vivid scene when she reached for a banana on a tree. Her grandfather quickly pulled her back by the arm and saved her from a nest of snakes that was hidden in the bananas. He furiously chopped off heads and stabbed snakes to pieces.

The fury with which he attacked those snakes also marked Shiva's treatment of his wife, Rebecca, whom he beat senseless whenever the mood struck him. He also brutalized his eight children as well.

Why? Shiva had the right to vent his anger whenever he wished. He was a light-skinned male with straight black hair, a Hindu from East India. Most importantly, he had no African blood coursing through his veins. And, as Sital explains, Rebecca — like most citizens of Trinidad — was a mix of races. The practice of wife-beating was common among Trinis, especially if one's wife was mixed.

Sital, who holds a master's in fine arts from Hunter College and whose work has appeared in The New Yorker and other publications, suffuses her memoir with irony and poetry. And although the poetic descriptions at times seem heavy, the ironies inherent in this story about an island named for the Blessed Trinity make this account riveting.

From Aug. 3, 2014, to May 15, 2016, the Islamic State group abducted nearly 7,000 Yazidi men, women and children. Only 2,587 have been rescued. The rest are dead or missing.

Dunyah Mikhail shares the stories of approximately 20 female survivors of the Yazidi genocide in her disturbing memoir, The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq.

Mikhail first learned these stories from Abdullah Shrim, also a Yazidi and the beekeeper of the title, who gave up his job farming bees to rescue Yazidi women. First, his cousin, who wanted to escape her abductor, contacted him. Then others heard about her rescue and called him.

Dunyah Mikhail (Robert Akrawi)

Soon Shrim connected with a network of helpers, and, by book's end, he had freed over 300 captives. Yet, as Mikhail reminds us, there are more than 4,000 who are still in captivity.

ISIS' attempts to exterminate the Yazidis began when the terrorist group — also known as Daesh — entered Northern Iraq in the Sinjar Mountain region. Here, Mikhail explains, the Yazidis practiced a pre-Islamic religion, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia, that teaches the importance of hospitality.

Declaring the Yazidis to be pagans, the Daesh tried and mostly failed to convert them to Islam. They shot the men and adolescent boys. They moved the younger boys to camps where they studied the holy texts of the Quran while learning to kill. They kidnapped the women and girls, taught them to make chemical weapons, and forced them to pray before they were repeatedly raped, beaten and sold as sex slaves.

As extremist Sunni Muslims, Daesh applied a jihadist interpretation to the Quran and believed that one was allowed to rape and enslave Yazidi women as part of the spoils of war. Their stories are horrific and almost too painful to read. Unfortunately, they feel somewhat jammed together here, as each one could be expanded to fill an entire book.

Mikhail, who adds her own story to those of the escaped women, was born in Baghdad in 1965 and is an award-winning poet. She worked as an Iraqi journalist until the mid-1990s, when she was forced to leave Baghdad for the United States because of threats from the authorities.

Although Mikhail is not a Yazidi, she was able to learn about their religion and culture during her interviews. She says little about her own religious inclinations but notes that she was especially close to her grandmother and recalls her grandmother's rosary beads and her devotion to the Virgin Mary.

Mikhail also includes a few of her poems, one containing a brief history of Iraq from Sumerian times. She recalls her times with her grandmother and how she would murmur the words to the Lord's Prayer.

The horrifying tale of the Yazidi genocide, however, is the real story behind the book. Mikhail's fairly ordinary remembrances give context to that story, as they accentuate its horrors.

As Helene Stapinski researched stories for The New York Times and other publications, she met fascinating characters and visited interesting places like Hong Kong, Egypt and Thailand.

But no place could compare to Bernalda, an impoverished, out-of-the way town in southern Italy. And no person could equal Vita Gallitelli (1852-1915), Stapinski's great-great-grandmother who grew up in Bernalda.

Vita is the unlikely hero of Stapinski's third book, Murder in Matera: A True Story of Passion, Family, and Forgiveness in Southern Italy. As Stapinski first saw it, Vita and her husband, Francesco, had murdered a 14-year-old boy.

After Francesco went to jail, Vita, in her mid-20s, left Italy to come to America with her children in order to raise them and escape Italian prison. With her long black hair, dark eyes and a come-hither smile, she was also thought to be a loose woman — possibly a prostitute.

Growing up in Jersey City, Stapinski was born into a middle-class, Roman Catholic family. Like her ancestors, she attended a parochial school and worshiped at Mass every Sunday. She, therefore, found it difficult to believe that her great-great-grandmother could murder someone, and she wanted to learn whether the stories about her were true.

Since Vita could neither read nor write, and the family could provide no written records of letters or diaries, Stapinski decided to travel to Italy in order to research records concerning her family's past. She made two trips. The first, in 2004, yielded meager results, but the second, in 2014, was successful and formed the basis for this account. Stapinski's book includes material from her own observations, interviews with the townspeople, and records from a 600-page criminal file of events that occurred more than a century ago.

Advertisement

The memoir is set against a backdrop of Stapinski's love/hate relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. In her first trip to Italy, she, who considered herself a fallen away and angry Catholic, says the rosary and attends daily Mass, but only because she is frustrated with her inability to find any documents about her family.

On her second trip, she has an epiphany in one of Matera's painted caves — dubbed the Sistine Chapel of Matera — and she understands the meaning of forbidden fruit and the way the notion plays out in her family.

Pears, for example, played a significant role in Vita's long ago crime, which leads Stapinski to muse on the book of Genesis with its stories of both forbidden fruit and murder. She also discusses pears in The Odyssey, in St. Augustine's Confessions, and in Wallace Stevens' "A Study of Two Pears."

Stapinski presents her findings in a bright, cheerful tone and often uses a casual, street slang, like when she calls followers of St. Augustine his "buddies." The voice is somewhat jarring, but one becomes accustomed to it, and it keeps the wealth of information from weighing down this deceptively lighthearted story.

[Diane Scharper's most recent book is Reading Lips and Other Ways to Overcome a Disability. She teaches "The Art of Memoir" for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Institute.]