A silhouette of the statue Hands Across the Divide is pictured in Londonderry, Northern Ireland. The bronze was unveiled in 1992, 20 years after Bloody Sunday, when British troops killed 14 Catholic demonstrators. (CNS/Reuters/Clodagh Kilcoyne)

Sitting beside his dad as he raced a train in his silver Jaguar is a highlight of Stanislaus Carberry's childhood – before his father was shot dead by British soldiers.

Now 49 years on, Carberry hopes to win another race, to reach the truth of what happened to his "best friend" before the U.K. government enacts a controversial ban on prosecutions, inquests, court proceedings, criminal and ombudsman investigations connected to Northern Ireland's sectarian conflict.

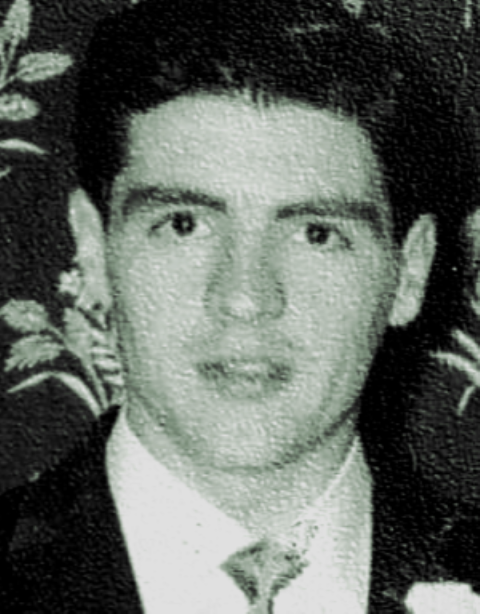

Stanislaus Carberry Sr., a 34-year-old Irish Republican Army volunteer, was shot three times in the back after he hijacked a car in Belfast on Nov. 13, 1972. His son, who was 8 at the time, wants the truth about his death. (Courtesy of Stanislaus Carberry Jr.)

More than 3,500 people were killed in the 30 years before the 1998 Good Friday Agreement brought peace to the United Kingdom territory.

Of these, 363 have been officially acknowledged as a result of security force action, but some nonprofits in the sector believe that the state could be involved in as many as a third of conflict-related deaths.

Christened Stanislaus after his aunt, a Catholic sister, Carberry Senior, 34, was shot three times in the back after he hijacked a car in Belfast on Nov. 13, 1972. The inquest into his death, which did not solve the killing but concluded it was suspicious, heard that he had fired a weapon from the passenger seat of a blue Vauxhall vehicle.

But witnesses in the civil suit, brought by Carberry's eldest son and namesake against the U.K. minister of defense, testified that Carberry, an Irish Republican Army volunteer, was shot while driving.

An eyewitness, Rosetta McGlinchy, then 16, testified via Zoom from Canada for the suit that Carberry collapsed after getting out of the car. No weapons were found at the scene.

A number of shots came from some of the 16 soldiers in the vicinity at the time, according to McGlinchy's lawyer, Gary Duffy.

This is one of a number of legal cases being heard, or currently under consideration in Northern Ireland. It is unknown how many would be finalized if the U.K. government enacts a law to end them. The government has claimed that replacing prosecutions and civil actions with an "information recovery body" would help reconciliation in the territory. But critics say it is being done to protect military veterans from prosecution.

"It's little wonder that the government wants to shut down these cases. Without control of the courts it cannot control the narrative on the past," said Kevin Winters, whose firm KRW Law represents several victims.

The Catholic Church joined all political parties in this traditionally divided society to condemn the proposals, which Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis hopes to begin legislating before the end of the year. Several U.K. military veterans groups have applauded the proposals, saying they offer an effective amnesty against prosecution to police and soldiers active in Northern Ireland.

Calling it "a betrayal of trust," Archbishop Eamon Martin of Armagh criticized Prime Minister Boris Johnson's statement in July that the proposals would "draw a line under the Troubles."

Bishop Donal McKeown took aim at the proposals during Mass at St. Eugene's Cathedral in Derry in July, saying they would "prevent too much prying into dark corners of a dirty war."

He told NCR in a telephone interview that he was "not confident" that the plans would be withdrawn. "It suits the majority across in England," he said. "So if it suits them it'll go through."

He said the government "seems set on ensuring that it doesn't ruffle the feathers of the establishment or cast any aspersions on their wonderful military."

"The last thing they would want would be a story coming out about young men who were sent in to do dirty jobs as members of the armed forces and being involved in all sorts of things that did not reflect on the glory of the state," McKeown said.

Advertisement

In October, the trial of a former British soldier charged with attempted murder in the 1974 death of John Patrick Cunningham was halted when the accused died. The 27-year-old, who had learning difficulties, was shot in the back as he ran from an army patrol on June 15, 1974.

Dennis Hutchings, 80, who commanded the British platoon in County Tyrone that day, died with COVID-19 in Belfast, where he was to appear in court. He had already pleaded not guilty. He was buried in a military funeral in Plymouth, England, on Nov. 11.

The civil case against the British army for unjustified use of force against Carberry is expected to hear the testimony of at least two former British soldiers when it resumes in the Belfast High Court on Jan. 22. Former soldiers known as 'B' and 'C' will likely testify remotely. 'Soldier A' died in the summer.

Carberry, 8 when his father was killed, spent most of his adult life pursuing the truth. With the help of the organization Relatives for Justice, which also provided him with psychological therapy, he was directed to lawyers who have acted for him in claims, including the failure of the state to properly investigate his father's death.

"This is a tactic from the British government and the minister of defense," Carberry told NCR in an interview, "to delay, delay, delay until people have passed away."

He believes U.S. President Joe Biden could have some influence in persuading the U.K. government to drop these proposals.

"America has spent a lot of money on peace in this island and you can't have peace without justice," he said.

A seagull flies in front of a mural which shows a group of men, led by then-Fr. Edward Daly, right, carrying the body of shooting victim Jackie Duddy during 1972's Bloody Sunday in Londonderry, Northern Ireland. In 2010, then-British Prime Minister David Cameron apologized for British troops killing 14 Catholic demonstrators that day. Daly, bishop of Derry 1974 to 1993, died in 2016. (CNS/Reuters/Cathal McNaughton)

Brendan Boyle and Brian Fitzpatrick, both Catholic U.S. representatives from Pennsylvania, led a letter to Johnson in September, calling the proposals "a serious mistake" and asking him to reverse them.

Carberry, who promised his 90-year-old mother, Gemma, he would not rest until he gets the truth, believes the proposals violate his human rights.

"If they do this, what country is going to trust them ever again?" he asked.

By January, Northern Ireland's Public Prosecution Service had decided to prosecute nine individuals for Troubles-era crimes and was due to consider another 46 files, which included 17 murders and 12 abductions, Queen's University Belfast Law professor Louise Mallinder told NCR.

"All of these pending prosecutorial decisions would be closed by the amnesty," she said.

Some 200 other cases under review by the independent Operation Kenova could lead to further referrals for prosecution, and Northern Ireland's police Legacy Investigations Branch has 929 cases involving 1,184 victims, although only 33 are being actively investigated.

"The ban on civil proceedings would bring an immediate and permanent end to victims' access to civil remedies," Mallinder said. "This would undermine the rule of law and the U.K.'s obligations to provide victims of human rights violations with access to justice."

She helped draft a response to the proposals, finding that they "go further" than the 1978 amnesty proposals of Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet, which excluded civil cases, sexual violence cases and those already before the courts. They also applied only to five of the 17 years of his dictatorship.

Constable Harry Beckett, 47, died after being shot in the face by an IRA gunman on June 30, 1990. His wife Isobel, who stopped eating after his death, died five months later. Beckett's daughter Kathryn Johnston wants the truth about his death. (Courtesy of Kathryn Johnston)

"I'm sure there are dictators and despots around the world rubbing their hands with glee about this," said Kathryn Johnston, who lost her father in the conflict. "They are probably thinking if the mother of all parliaments can pass this, we can get away with it," she told NCR.

Johnston's police officer father, Constable Harry Beckett, 47, died after being shot in the face by an IRA gunman on June 30, 1990. Her mother Isobel, who stopped eating after his death, died five months later.

Beckett and his colleague Constable Gary Meyer, 35, were killed with a Browning pistol, which Johnston believes came from a weapons dump where it was returned after ballistics testing.

"More effort should have been put into trying to get a conviction," she said, particularly since her father, a former British soldier, was a police officer at the time.

On the contrary, various items at the scene went missing and even the police uniform he had been wearing was disposed of.

Johnston is suing the police service for negligence for its "failure to conduct an investigation into the murder of the Deceased in compliance with Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)."

"I want to look them in the eye," she said of those who contributed to the circumstances of Beckett's death and its investigation. "I want to tell them that my father was not an expendable piece in their sick game."

"In this country you have to fight tooth and nail for any answer or any truth, and that's wrong," said Johnston who, like Carberry, has spent decades looking for answers.

A member of the Commission for Victims and Survivors, she has learned how other families are also struggling for answers, like a mother of five the British army shot dead 50 years ago while she was bringing in laundry.

Johnson was not surprised, but "angry" by the government's proposals. "Not just for my sake, but for the sake of everybody that this is going to affect."