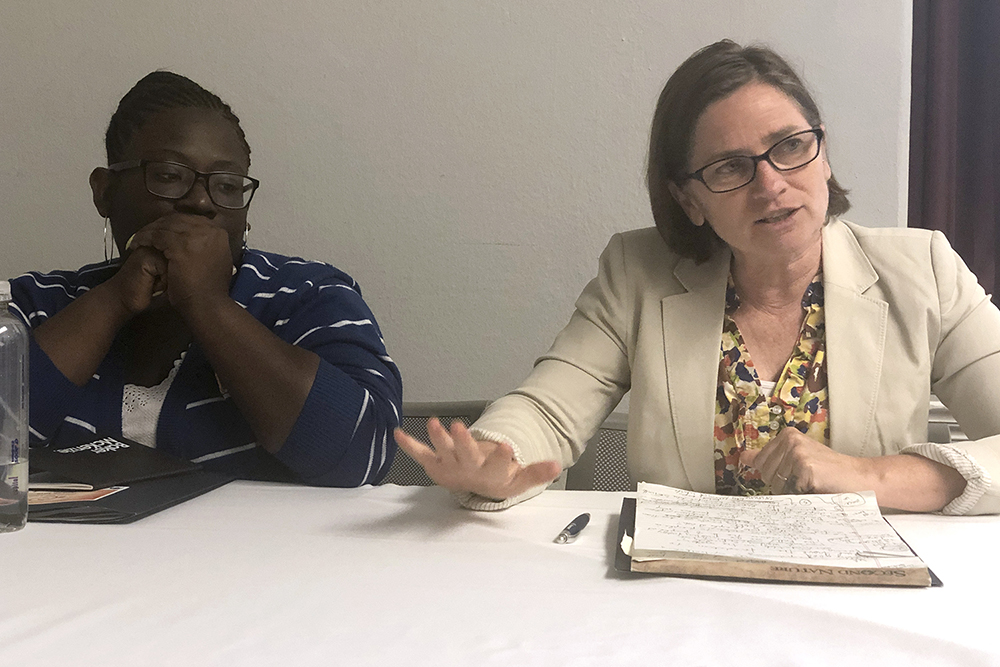

Evelyn Chumbow, left, a survivor of child labor trafficking, and Hilary Chester, right, associate director for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Anti-Trafficking Program, address an audience June 26, at a conference on Capitol Hill about human trafficking. (CNS/Rhina Guidos)

The U.S. Capitol is seen in Washington July 3. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

At age 9, growing up in Cameroon, Evelyn Chumbow had dreams of coming to the United States, thinking she'd live like the characters in TV shows such as "The Cosbys" and "The Fresh Prince of Bel Air," which she believed depicted life here.

When a relative offered her the opportunity to come to the U.S. through an arrangement with a family in her hometown, she was ready to embark on that life.

"I was just excited," she said. "I could never think that I'd come to the U.S. and become a victim of modern-day slavery or end up in foster care."

But that's exactly what happened and that's the experience she talked about June 26 to participants of a daylong human trafficking conference hosted on Capitol Hill by the National Advocacy Center of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the District of Columbia Baptist Convention.

Participants, who lobbied U.S. lawmakers after the conference for tougher legislation to combat the problem, learned about its complexities and its global dimensions:

- An estimated 40.3 million people are enslaved.

- Of those, 24.9 million are in forced labor (including sex trafficking).

- 15.4 million are in a forced marriage.

Chumbow, who was 11 when she became a victim of forced labor, fit many of the characteristics of trafficking victims: 25% of those trafficked are children and over 70% of those trafficked are women and girls. Chumbow thought she was coming to the United States to be adopted by a family.

Instead, she was in a group of girls brought in under one passport and then sent off to become a domestic worker in a house in Maryland, where, at age 11, she cooked and cleaned and took care of other children, receiving no salary. The relative who had made the arrangement, she later found out, had sold her for $1,000 to the household where she suffered a variety of abuses.

Unknowingly, she had been brought to the country illegally and didn't know where to go and what to do about her situation. Eventually, she escaped, helped law enforcement convict her abuser and embarked on a long journey of healing, which now involves educating the public about human trafficking.

There's a lot of "separation" of different aspects of human trafficking, but to address the problem holistically, those working to eradicate it need to look at forced labor along with issues of immigration and sex trafficking, the topic which commands much of the attention in human trafficking advocacy, she said.

"I'm a survivor of labor trafficking," Chumbow said, but there were different abuses taking place and she also was dealing with an immigration situation.

Human trafficking can affect any number of vulnerable individuals, such as incoming immigrants from the so-called "Northern Triangle" countries of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, but also vulnerable people inside the United States, including those in tribal communities, said panelist Hilary Chester, associate director for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Anti-Trafficking Program. She said legislation to combat the problem must take those and other factors into consideration. But enforcement, which would go a long way in solving the problem, is often lagging.

"Because there aren't good opportunities in their home communities or because there's a lot of criminality, there's a lot of impunity for the perpetrators in these communities," Chester said. "People are leaving, searching for other opportunities, which then puts them in front of exploitation."

Even those already living in the U.S. can face similar situations when they leave their support networks, their communities, which is exactly the situation that makes them more vulnerable, Chester said.

The U.S. Capitol is seen in Washington July 3. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Conference organizers offered a wide range of human trafficking examples, which they said can involve modern-day slavery, as well as the exploitation of a person through force, fraud or coercion, which can include sex trafficking, forced labor, domestic servitude and any person under 18 involved in a commercial sex act.

Neha Misra, of the Washington-based Solidarity Center, said that even the popular image most people have about human trafficking can prove complicated.

"When people think about human trafficking, often they first think about sex, but they also think about criminal gangs and syndicates and that it's all underground, and it's not," she said. "It's all about the way we have set up our world economy, the greed that we can see, about how corporations run their businesses and how governments do not respect human rights and worker rights, and that is what makes people vulnerable. It's not just about criminal syndicates."

Most human trafficking around the world involves forced labor, said Misra, to produce items consumers buy on a regular basis.

For example, she said, a trafficker used a group of eight boys who had entered the U.S. as unaccompanied minors in 2014 to clean cages and do other tasks for a poultry farm, one of the largest egg producers in the country. The boys had been living in squalid conditions outside Columbus, Ohio, and paid $2 a day for their work, which included debeaking hens. The company said it was unaware that the subcontractor who brought in the workers was a human trafficker, and the company was never prosecuted for the crime.

"The company said, 'Well, we didn't know,' " Misra said. "Those workers are in your workplace every day. How can you not know that? You didn't know that there was abuse in your supply chain? If they don't know, it's because they don't want to know."

Citizens can demand that government hold those companies accountable, Misra said, and consumers can go online to look for information about violations.

In "hubs" of human trafficking such as Detroit, faith-based groups such Sisters of the Good Shepherd have tackled part of the problem by offering services to female victims of human trafficking, including counseling, housing, career training, prevention programs and even educating the community about human trafficking through its Vista Maria center, formerly the House of the Good Shepherd.

Advertisement

Bailey, a 20-year-old who participated in one its programs, attended the conference and credited the help she received at the Vista Maria center with giving her a new outlook on life and now counts herself among one of the lucky survivors of human trafficking. The young woman, who did not give her last name, shared her story of abuse at a young age, her parents' addictions, which led to a struggle of her own with drugs.

For years, she was involved in a cycle of addiction, sexual exploitation and depression. Vista Maria helped her with housing, counseling and toward a career path as a welder, which has helped her financially stand on her own.

"I am here today to educate all of you that there isn't one kind of story for sex trafficking," she said. "Without long-term treatment, I would not be where I am today. It wasn't that long ago that I didn't want to live because of my depression. Today, my future is very promising. Please help us pass laws that support girls and women who have experienced sexual exploitation and help them have a future beyond trafficking."