With the headquarters of the ruling party burning in the back, supporters of Niger's ruling junta demonstrate July 27 in Niamey, Niger. Defense chiefs from the West African regional bloc, ECOWAS, were to meet Aug. 17 in Ghana to discuss Niger's crisis after a deadline passed for mutinous soldiers to release and reinstate President Mohamed Bazoum or face military intervention. (AP photo/Fatahoulaye Hassane Midou, file)

When army officers seized power in the West African state of Niger on July 26, overthrowing and detaining President Mohamed Bazoum, there were fears of domestic chaos and foreign intervention.

The coup, headed by Gen. Abdourahmane Tchiani, commander of the presidential guard, makes Niger the latest of several West African states to revert to military rule — in the face of Islamist insurgencies, chronic underdevelopment and the probing influence of Russia.

The dramatic showdown is prompting reflection, not least in the region's small but influential Catholic Church.

"Niger was very poor already — and though its people are accustomed to harsh realities, daily life looks set to become even harder now, with shortages of power, food and medicines," Fr. Mauro Armanino, a priest with the Society of African Missions, told NCR from the capital, Niamey.

"The new self-appointed government has spoken of a transition to new elections, but is still holding the president prisoner," said Armanino. "If foreign powers intervene, many of our own Catholic community, who've come from Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso and elsewhere, could find themselves targeted."

Tchiani and his coup partners set up a National Council for Safeguarding the Homeland, closing Niger's borders and suspending political parties, declaring they had toppled Bazoum because of "bad governance."

Niger's President Mohamed Bazoum smiles before a working lunch with French President Emmanuel Macron, Feb. 16 at the Elysee Palace in Paris. (AP photo/Michel Euler, file)

The charges were adamantly denied by the president, who insisted Niger had made "remarkable progress … under democracy" towards improved security and economic growth through partnerships with the United States and European countries.

Meanwhile, the coup was condemned by the U.S., European Union, United Nations and African Union, as well as by ECOWAS, the Economic Community of West African States, which warned it could deploy military force unless constitutional rule was restored by Aug. 6.

With neighboring military regimes in Burkina Faso and Mali supporting the coup, Tchiani and his officers ignored the deadline and named a provisional government on Aug. 10, confident they could face down sanctions and saber-rattling.

And although ECOWAS still stood ready to send in troops, mostly from Nigeria, Senegal and Ivory Coast, at a second emergency summit the same day, other governments, including those of Guinea, Algeria and Chad, also warned against military intervention.

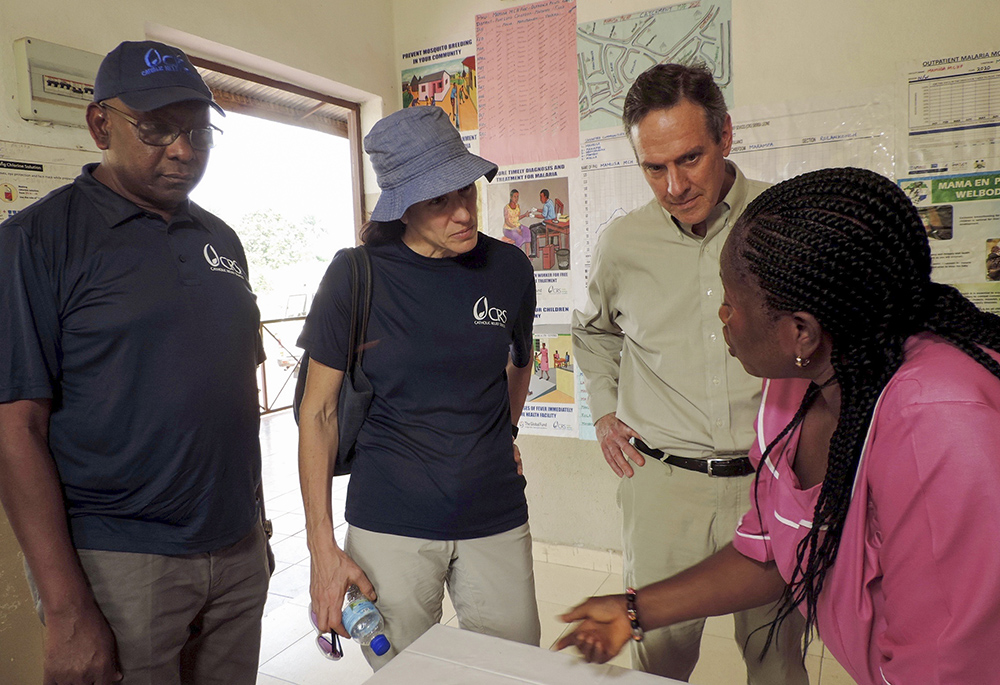

"Whatever happens, the existing fragility and vulnerability of people, especially women and children, must be taken into consideration," Jennifer Overton, West Africa regional director with Catholic Relief Services, told NCR.

"Our programs against food insecurity and malaria are moving ahead, and we're hoping for a diplomatic solution," said Overton. "But if anyone takes action to restore democracy in Niger, they should think carefully about the likely impact on its people."

Jennifer Overton, West Africa regional director with Catholic Relief Services (second from left), stands with CRS president and CEO Sean Callahan during a visit to a health unit supported by CRS in Port Loko District Sierra Leone in 2020. (Courtesy of Catholic Relief Services)

The coup is the fifth since Niger's independence from French rule in 1960, and follows at least two parallel plots against Bazoum since his April 2021 inauguration.

There are fears it could weaken the fight against militants linked to Islamic State and Al-Qaeda, who've swept across the Sahel region since the 2011 civil war in Libya, perpetrating massacres and occupying swathes of territory, despite the presence of some 5,000 French troops.

Tensions had been growing with army leaders, said Armanino, because of Bazoum's offers of clemency to imprisoned jihadi fighters, as well as over the presence of foreign forces.

There are also anxieties, however, about the influence of Russia, which has called officially for a return to "legal order," but is active in the mineral-rich region through the mercenary Wagner Group, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, whose fighters were reported to be flying in after the coup.

Meanwhile, with the U.N. citing over 5.2 million refugees, internally displaced and threatened people across the Sahel, including almost 666,000 in Niger itself, aid organizations are warning of the coup's damaging consequences at a time spiraling poverty, hunger, unemployment and insecurity.

Members of a military council that staged a coup in Niger attend a rally Aug. 6 at a stadium in Niamey, Niger. (OSV News/Reuters/Mahamadou Hamidou)

Religious leaders have been at the forefront of peace efforts.

A Muslim delegation from neighboring Nigeria held talks with the junta on Aug. 12, while the Catholic Regional Episcopal Conference of West Africa, or RECOWA, a grouping of 11 national church hierarchies, said its members were praying for a "peaceful and definitive resolution."

In a stark follow-up appeal a few days later, ahead of the second ECOWAS summit, the bishops warned against outside military intervention and called on West African governments to show "restraint, discernment and responsibility" when lives were at stake.

Terrorism had already left a "macabre toll of widows, orphans, displaced persons, the hungry, the maimed and so on," they added, and lessons should be learned from the "tragic example" of past Western intervention in Libya.

"We, your pastors, are convinced, and the history of peoples teaches us, that violence does not solve any problem, not even the one that triggered it," the West African bishops said.

Bishop Laurent Dabiré of Dori, Burkina Faso, is pictured in a July 8, 2017, photo. (CNS/Courtesy of Aid to the Church in Need)

Similar appeals, highlighting the failure of past military interventions, have been issued by national church leaderships, as well as by the Catholic Church in Burkina Faso, which shares a joint bishops' conference with Niger.

"How can we not be worried when the specter of war appears in the solutions to end the crisis envisaged, suggesting a possible 'second Libya,' even though the fatal and disastrous consequences of the destabilization of this country continue to make the populations of the Sahel suffer terribly," the conference's president, Bishop Laurent Dabiré, said in a message from Burkina Faso's capital, Ouagadougou.

"This is why we do not believe at all in the solution of force, to which we clearly say no," he said.

Niger's some 25,000 Catholics, spread over the Archdiocese of Niamey and Diocese of Maradi, make up a small fraction of the country's mostly Muslim population of some 23 million.

The church was severely affected by January 2015 anti-Christian riots, which left at least 10 dead and dozens of properties destroyed, and has been forced to close parishes and schools in some rural areas because of the Islamist threat.

Men start reconstruction on a church Jan. 23, 2015, in Niamey, Niger, that was destroyed in violent protests against French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo's cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. (CNS/Reuters/Joe Penney)

Its leader, Archbishop Djalwana Laurent Lompo, was caught out by the closure of Niger's borders while abroad, and was still trying to return to Niamey in mid-August.

In an Aug. 10 message, however, he reaffirmed the church's "commitment to peace and justice," and called for days of prayer and fasting to save the country "from war and chaos."

Meanwhile, Fr. Boya Johny, chargé d'affaires at the Vatican's Ouagadougou embassy, which also covers Niger, told NCR that the ambassador, Archbishop Michael Crotty, was also abroad, but confirmed the Holy See was following the situation "with great concern."

Armanino, from the Society of African Missions, told NCR he was "surprised and disappointed" by what he called the Vatican's lackluster response.

Vatican News has covered the coup's aftermath, reporting the warnings against outside intervention, and noting how the Niger junta was "exploiting anti-French feelings" to "shore up its support base," thus creating an opening for Russia's Wagner Group.

But Armanino said he's aggrieved Pope Francis had made no mention of the crisis by mid-August, when local Catholics expected at least "some small word to encourage dialogue and a peaceful solution."

Even if Rome stays silent, Overton at Catholic Relief Services thinks church leaders have a significant influence throughout West Africa, through key figures such as Mali's Cardinal Jean Zerbo and Burkina Faso's Cardinal Philippe Ouédraogo, and is certain their carefully considered calls for calm will be heeded.

Advertisement

Overton focused on the vital humanitarian needs on the ground, and called for efforts to continue by church leaders and Catholic organizations like CRS to raise international awareness.

"There are grave issues here, with young people left disappointed, disenfranchised and disillusioned, and rural communities facing total neglect, as the rich get richer and resources and investments are channeled disproportionately into the cities," the CRS regional director told NCR.

"If the Niger crisis helps address the root causes of these problems, and makes people aware of the sufferings here, just as they are of Ukraine or Syria, the whole region could emerge stronger. But that will require efforts by the entire international community — at a time when many Westerners have never even heard of these countries," she said.

For now, at least, Tchiani and his coup partners seem confident they can hold on to power, announcing on Aug. 14 that they planned to prosecute the deposed Bazoum for "high treason."

And while the force assembled by ECOWAS — grouping 15 countries speaking French, English and Portuguese — stands ready, it's unlikely to be deployed, following church warnings, for fear of major bloodshed.

In Niamey, Armanino says the coup hasn't held back the rain and sandstorms to which the region is prone each summer. Those now citing geopolitical concerns and demanding intervention have probably never suffered power cuts and food shortages themselves, he points out, or learned to listen to the anxieties of those yearning for a better life.

"Although no one should suggest a coup was the only solution, it should be remembered that the military forms part of the political structure here," the priest told NCR.

"And although the international community insists Niger had an democratic system, this isn't really true given the problems we've faced with past elections and the dominance of power interests," he said. "While there was also opportunism on the side of the coup leaders, who feared being sidelined, it's always the poor who lose out from power struggles like this one."