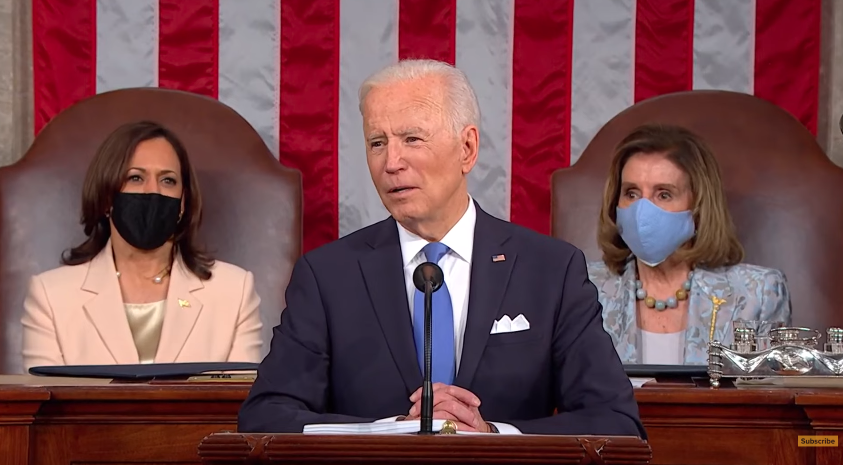

President Joseph Biden speaks to a joint session of Congress April 28. Seated behind him are Vice President Kamala Harris and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. (NCR screenshot).

President Joe Biden delivered his first address to Congress last night. It is hard to know how many people watched it, or if they watched it, if they did so free of partisan commentary. Biden remembers the time when a State of the Union address was an opportunity for the president to address the nation as well as Congress, but now everything comes through Instagram and Twitter, and filtered through various ideological lenses.

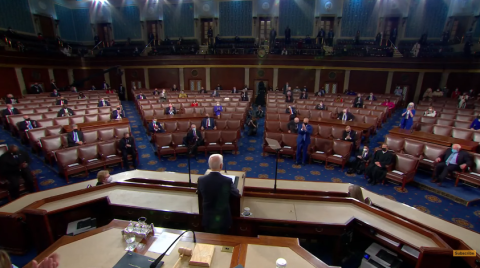

Like everything else this year, the setting was abnormal. The chamber of the House of Representatives normally can hold all 435 members of the House, the 100 senators, the members of the Cabinet, some Supreme Court justices and diplomats. The gallery would normally be packed with guests. This year, due to the pandemic, only 200 people attended.

What is more, the last time the entire nation watched this room for a prolonged period of time was during the attack on the Capitol — and on our democracy — on Jan. 6. Biden stood at a podium where only a few months ago, domestic terrorists tried to arrest the counting of the Electoral College ballots and chanted their desire to murder Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and then-Vice President Mike Pence.

Speaking of Pelosi, one abnormality this year would be welcome in future years: For the first time in our nation's history, two women, Pelosi and Vice President Kamala Harris, sat behind Biden while he spoke. "Madam Speaker. Madam Vice President," Biden began. "No president has ever said those words from this podium, and it’s about time." May that be the first of many times, although I think we can also look forward to the day when two men sit behind a woman president delivering a State of the Union address.

Only about 200 guests were allowed to attend President Joseph Biden's first speech to a joint session of Congress April 28, due to continuing coronavirus precautions. (NCR screenshot).

The most abnormal thing about Biden’s speech, however, was how normal it was. After four years of Donald Trump spewing his particular brand of dyspeptic, self-absorbed oratory, it felt a bit unfamiliar, and a bit exhilarating, watching Biden calmly discuss the challenges and the opportunities facing the nation, and discuss how he proposed to confront the one and exploit the other. A sense of déjà vu does not usually mix with the emotions kindled by promise, but when they do, the experience is centering. The speech felt like the country was getting back to normal.

The United States, in normal, pre-Trump times, believed democracy worked. Regrettably, Ronald Reagan pitted democracy against government, and set the terms of public policy for 40 years. The pandemic brought into sharp relief what had long been obvious to those of us schooled in Catholic social doctrine: Reaganism hollowed out the government’s ability to achieve its foremost objective, the common good.

But, the will of the people continued to voice skepticism about government overreach and the most memorable line from a State of the Union speech by the first Democratic president after Reagan, Bill Clinton, had the flavor of capitulation: "The era of big government is over."

Biden announced that government focused on the common good was back and that the democratically expressed will of the people insisted on a more activist government. He was explicit about the connection:

We have to prove democracy still works. That our government still works — and we can deliver for our people. In our first 100 days together, we have acted to restore the people’s faith in our democracy to deliver. We’re vaccinating the nation. We’re creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs. We’re delivering real results to people, they can see it and feel it in their own lives. Opening the doors of opportunity. Guaranteeing some more fairness and justice.

Biden’s speech also included some rhetoric that suggested the Democratic Party was getting back to normal. Discussing the infrastructure bill that is in front of Congress now, the president said:

Now, I know some of you at home are wondering whether these jobs are for you. So many of you, so many of the folks I grew up with, feel left behind, forgotten, in an economy that's so rapidly changing — it’s frightening. I want to speak directly to you, because if you think about it, that’s what people are most worried about. Can I fit in? Independent experts estimate the American Jobs Plan will add millions of jobs and trillions of dollars to economic growth in the years to come. It is an eight-year program. These are good-paying jobs that can’t be outsourced. Nearly 90% of the infrastructure jobs created in the American Jobs Plan don’t require a college degree. 75% don’t require an associate's degree.

There are several ways political strategists characterize voters who do not have a college degree — "former Democrats" and "Trump voters" being the most common — but the results of last year's election show that Biden won because enough working-class voters in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin voted for him. For the first hour, he spoke almost exclusively about the pandemic and the economy, most of it directed at the voters of Pittsburgh and Grand Rapids and Green Bay.

Advertisement

The president delivered a short laundry list of social issues towards the end of his speech. His comments on gun reform were sensible but likely not to have effect. He misfired in discussing immigration, first touting comprehensive reform and then offering the legislative equivalent of a plea deal: "Now, look, if you don't like my plan — let’s at least pass what we agree on." He urged Congress to at least extend protection for the Dreamers and farm workers, undercutting the pressure to come to agreement on a comprehensive bill.

It was remarkable that when the president spoke about protecting the right to vote — ("And if we are to truly restore the soul of America — we need to protect the sacred right to vote.") — the camera showed Sen. Lindsey Graham unwilling to applaud.

Throughout the speech, Biden inserted ad libs in which he spoke familiarly with the audience, and even complimented the assembled politicians at several points, both Democrats and Republicans. Biden, though president, is still a man of the Senate. Trump was an outsider to politics. Barack Obama served in the Senate, but only for four years, before being elected president. (Two of his four years, he was campaigning for the White House.)

Presidents George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter were all governors, not members of Congress, when they were elected to the presidency. It would be wonderful if Biden can conjure up the legislative record assembled by the last man of the Senate, Lyndon Baines Johnson, to become president. It is doubtful given the polarization in the country.

I do not know if young people who are preparing to register and vote for the first time were watching. It is hard to imagine to what they might have objected in Biden’s speech. I suspect that some of the culture warriors on both the left and the right will be distressed that Biden mostly ignored the neuralgic issues that fill the coffers at their special interest organizations.

But the voters who decided the last election — working-class voters who voted for Obama, then for Trump, and then for Biden — this was a speech for them. They are the people who will decide next year's midterms too. Joe Biden is not the greatest orator, but he connected with average Joes last night. It was not the best speech we have heard. It was some of the best politics we have heard in a long time.