Migrant farmworkers harvest romaine lettuce April 17, 2017, in King City, California. (CNS/Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

As a child working in the fields in Buckeye, Arizona, David Damian Figueroa remembers the intense heat. Many farmworkers around him suffered heatstroke or fell ill. When he would complain to his mother about the heat, she would tell him to repeat the phrase, "barbas de oro," calling on God to bless the farmworkers with a cool breeze or dust devil.

Today, farmworkers are facing even more extreme heat conditions, with temperatures approaching 120 degrees in some areas.

David Damian Figueroa watches as Dolores Huerta addresses the crowd at the pre-reception for the premiere of the documentary "Dolores." (Courtesy of David Damian Figueroa)

Now director of development at Farmworker Justice, Figueroa works to empower migrant and seasonal farmworkers by improving their living and working conditions, immigration status, health, occupational safety and access to justice.

His Catholic faith, which inspires him in his work, also reaches back to those early years in Arizona, when he recalls images of La Virgen de Guadalupe on his kitchen calendar and his mom praying the rosary. Before heading into the fields every day or before snacking on burritos at lunch, Figureoa remembers his family making the sign of the cross.

In addition to heat, other challenges today's farmworkers face include immigration status, lack of housing, unjust wages, little to no worker protections, intense wildfire seasons and grueling physical labor. For many, their Catholic faith provides hope and comfort during what is otherwise exhaustive and demanding work. At the same time, the church is also involved, through parishes and other institutions, working for justice and building community for farmworkers.

Current working conditions

Figueroa now lives in the Coachella Valley, a place known for agriculture and record-breaking heat. It also is home to many agricultural workers and has a devoted Latino Catholic community in the east valley.

Leydy Rangel, national communications manager for the United Farm Workers and daughter of undocumented farmworkers, said her family also struggled with extreme heat in the Coachella Valley.

"Up until 2015, my family and I didn't have AC," Rangel told NCR, explaining that this is a common experience among migrant families. "For most of the farmworkers who live in the Eastern Coachella Valley, we don't have a way to come home to cool our bodies down."

Migrant farmworkers with H-2A visas harvest romaine lettuce in King City, California, April 17, 2017. (CNS/Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

Rangel remembers summer nights when it was often cooler for her dad to sleep in the bed of his truck than in their home.

The coronavirus pandemic has only made working conditions worse for farmworkers.

Photo from Noé Montes, an artist who comes from a family of migrant farmworkers, taken in Mecca, California, during an annual visit of La Virgen de Zapopan to the United States in 2015. (Courtesy of Noé Montes)

Rangel said that at the beginning of the pandemic many farmworkers were not given masks or their employers attempted to charge them for personal protective equipment. Others reported that workers were required to bring their own toilet paper to the fields.

Because many farmworkers are undocumented, they are less likely to report workplace abuse.

"It's really hard to believe that we're still fighting for shade and water or fair pay, just basic things," said Noé Montes, an artist who comes from a family of migrant farmworkers.

Montes has captured photographs of farmworkers in the Coachella Valley, many of which capture the intersection with Catholicism.

Montes says that he believes that the Catholic faith is particularly strong in more recent immigrant families, especially from Mexico. "I've seen that it is a way for them to maintain a connection to the place that they just left," he said.

In Rangel's small rural community surrounded by predominantly agricultural workers, everyone has a statue or altar to La Virgen in front of their house. Usually when holidays come around, her neighborhood celebrates La Posada, but could not last year because of COVID-19.

"It gives us hope," she said about Catholicism and La Virgen de Guadalupe. "You know, farmworkers are some of the most skilled workers that we have in the U.S. yet, are still some of the lowest paid and most vulnerable workers. It feels good to have a sense of comfort."

"It's really hard to believe that we're still fighting for shade and water or fair pay, just basic things."

—Noé Montes, an artist from a family of migrant farmworkers

Church calls for justice for farmworkers

Just two hours from the Coachella Valley is another community in Southern California with a sizeable farmworker population: North County San Diego.

Many farmworkers from south of the border arrive carrying a rosary and picture of Guadalupe with them, said Appaswamy "Vino" Pajanor, the chief executive officer of the Catholic Charities Diocese of San Diego, which operates a shelter, La Posada de Guadalupe, for homeless men and farmworkers.

"They are strong believers and practitioners of our faith," Pajanor told NCR, noting that many farmworkers attend Mass at their local parish and have formed small prayer groups.

Farmworkers attend Mass at the Centro Sin Fronteras in El Paso, Texas, Sept. 25, 2019. The Mass was part of a pastoral encounter by U.S. bishops with migrants at the border. Two bishops who chair committees for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops applauded the passage of the Farm Workforce Modernization Act of 2019 (H.R. 5038).(CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Pajanor emphasized his admiration and respect for the work of farmworkers.

"The food comes to our plate, we go to the supermarket to buy them [the food], but we don't realize the toil, the sweat and blood sufferings that farmworkers have to undergo in order to get that healthy food, or any of the food that we have on our table," he said.

Many who work for farmworker justice were inspired by their parish priests.

Arturo Rodriguez, current president emeritus of the United Farm Workers, remembers learning about Cesar Chavez when he was 16 from his priest in San Antonio, Texas, who participated in the first strike in Texas. After college, Rodriguez went on to work full time with the United Farm Workers, working closely with Catholic bishops in Detroit, Michigan.

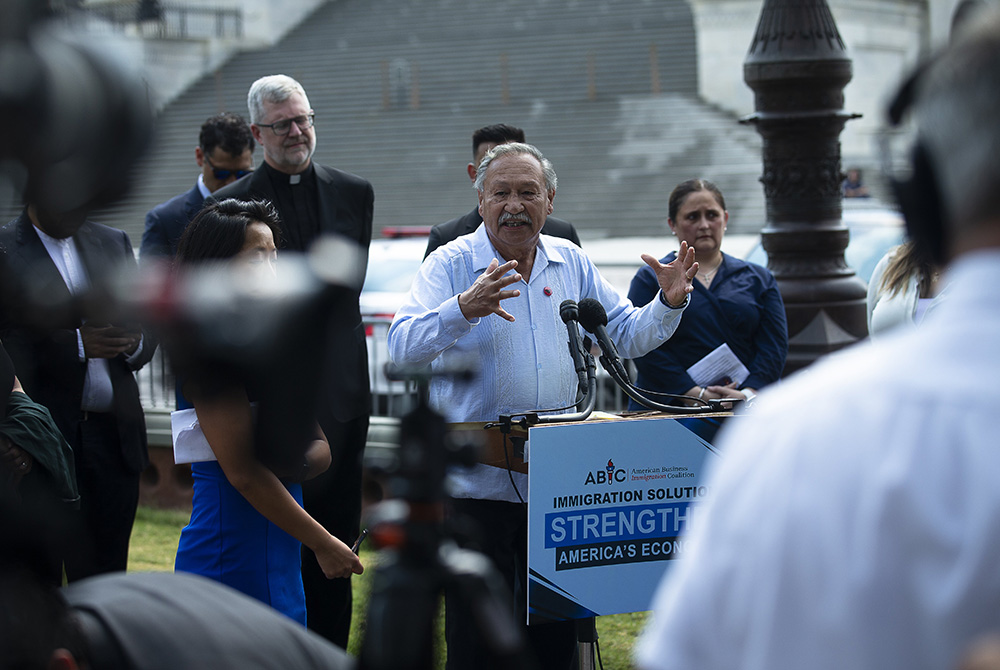

Arturo Rodriguez, retired chairman of United Farm Workers, speaks about immigration solutions near the U.S. Capitol July 21 in Washington. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

In the Coachella Valley, many farmworker advocates Montes talked to had been inspired by their parish priests. "The sense and the drive and the knowledge about how to organize, a lot of people pick it up in church," he explained.

Still a practicing Catholic, Rodriguez says one of the reasons he's stayed in the church is because he knows there are so many in the Catholic Church who believe in social justice and the right for fairness and dignity for all.

"As a result, it's [faith] always been part of the work that I do and my faith has kept me here, and kept me believing and hoping and praying someday that we are going to get immigration reform," he said.

Figueroa also believes that the farmworker movement is one rooted in justice, and that Catholicism has propelled the movement forward.

"Dolores and Cesar would say that, your [God's] hand, is going to protect us in this movement," he said. "Because you know, if God is with us, who can be against us?"

Advertisement