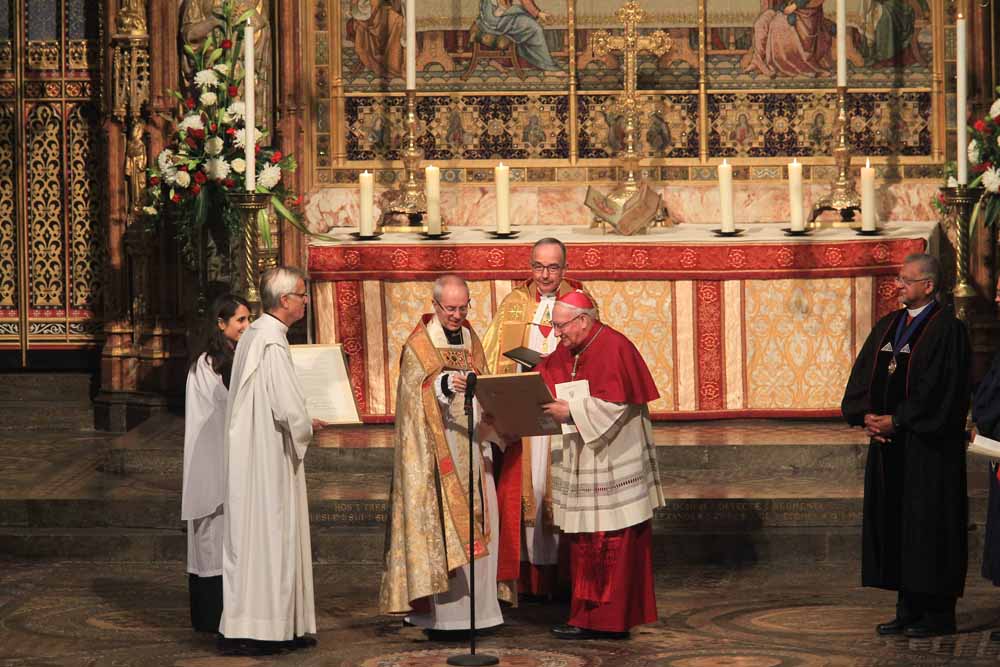

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby (center) formally presents the Anglican Communion's affirmation of the 1999 Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification. To Welby's right is Bishop Brian Farrell. (Andrew Dunsmore/Westminster Abbey)

Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran leaders in England united to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, pledging to work for a deeper unity between the divided denominations.

"We recall, with sadness, the cruelty and the deaths that blighted the ensuing decades," Dean of Westminster John Hall said at a service in London's Westminster Abbey Oct. 31. "Today we stand together, reconciled in Christ walking side by side, praying that we may be ever more united in our diversity."

The hour-long service in Westminster Abbey marked the high-point of events in England 500 years after Martin Luther's historic nailing of his 95 Theses to the door of Wittenberg Castle Church. Luther's public protest against the practice of selling indulgences, sparked the process that became known as the Reformation, which in turn divided Europe.

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby formally presented the Anglican Communion's affirmation of the landmark 1999 Catholic-Lutheran declaration on justification, which, he said, "resolved the underlying theological issues of 1517."

In response, Bishop Brian Farrell, the secretary for the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, said: "Let us be confident then that He who began this good work will carry it on to completion."

At the start of the service Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the Catholic archbishop of Westminster, processed in alongside Welby, who has said they are "the closest of friends."

The event combined the Anglican prayers of confession and absolution with Lutheran hymns and anthems.

In his sermon, Welby urged the Christian churches to further unite so they can more effectively address issues such as inequality, refugees, human trafficking, materialism and "the use of technology as a savior, rather than as a gift."

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby, Oct. 31 at Westminster Abbey in London (Andrew Dunsmore/Westminster Abbey)

In his sermon, Welby urged the Christian churches to further unite so they can more effectively address issues such as inequality, refugees, human trafficking, materialism and "the use of technology as a savior, rather than as a gift."

In Luther's day, the Gospel spoke prophetically "to human pride and sinfulness, of popes and archbishops and emperors," Welby told a congregation that included Lutherans from Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Estonia, Iceland, Finland, Latvia, China and East Africa.

He cited advances brought about through the Reformation.

"The church found again a love for the Scriptures, and seizing the opportunity of printing, gave them afresh to the world [and] confidence grew amongst the poor and oppressed that they too were the recipients of the promise of God of freedom and hope," he said.

To these he added the Counter-Reformation, which he said "renewed the places that the Reformation had not reached" and provoked "a competitive drive in missionary endeavor."

However, he added that each of these advances had a "dark side," listing conflict, individualism, division and military conquest.

He quoted the preacher to the papal household, Capuchin Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, who said that Luther would today oppose the notion of "self-justification" — "the claim of people today that they can save themselves thanks to their science, technology or their man-made spirituality."

The churches must keep setting aside their differences, Welby said, to witness effectively amid "difference of self-identity formation, of politics, of language, of our history as both oppressors and oppressed." These, he said, "all drive us, today, into self-reinforcing bubbles of mutual indignation and antagonism."

Advertisement

Nichols took part in the intercessions alongside representatives of various Lutheran churches. He prayed for greater ecumenical unity and "that the household of faith may be preserved from all that would further divide us." A Danish Lutheran pastor, the Rev. Susanne Freddin Skovhus, prayed for Pope Francis.

Nichols was one of more than a dozen Catholic clergy at the service, including six members of the Bishops' Conference of England and Wales.

A spokesperson for the bishops' conference said: "The desire for reconciliation is such that mistakes can be recognized, injuries can be forgiven and wounds healed.

"We also give thanks for the joy of the Gospel we share as Christians, express repentance for the sadness of our divisions and renew our commitment to common witness and service to the world."

Skovhus told NCR after the event that the service's Lutheran organizers had not described the service as a "celebration" of the Reformation, as such events have been termed in Lutheran-majority Denmark, because Lutherans in England "are quite sensitive" to the ecumenical diversity there.

Asked which Jewish representatives had been invited, she said none had been able to attend the service, which made no mention of Luther's anti-Semitism.

At a symposium following the service, scholars evaluated Luther's ongoing impact and Nichols and Farrell were spotted among the audience. University of Cambridge historian Eamon Duffy, who is a Catholic, argued that until the last 50 years' ecumenical engagement, the "age-old Catholic default mode" towards Luther was one of "rabid denunciation."

Duffy said a German historian, Fr. Joseph Lortz, "more or less singlehandedly brought about a revolution in Catholic thinking about Luther's Reformation," portraying the Catholic Church in Germany on the eve of the Reformation "as dominated by a corrupt hierarchy, promoting a mechanical and materialistic popular piety remote from the Gospels, and adrift from the patristic and medieval theological synthesis created by giants like [Thomas] Aquinas." He said that for Lortz the Reformation was "a tragic necessity." Nonetheless the priest believed Luther's views on sin and the doctrinal and sacramental system of the church led him into heresy.

Theologian Fr. Hans Küng provided a "key work," Duffy argued, in asserting that there was fundamental agreement between Catholics and Protestants on the issue of justification in his book Justification: The Doctrine of Karl Barth and a Catholic Reflection, which Barth endorsed.

Duffy noted that the future Pope Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger, in 1984 spoke of "two Luthers: an earnest and Christ-centered devotional genius on the one hand, and a radical theologian whose personality and intellectual radicalism led him into heresy on the other." This view "was prognostic" of the so-called "ecumenical winter."

By contrast, the 1999 Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification was a "real advance," Duffy said, and called for "a more hopeful Catholic reengagement with one of the giants of the Christian tradition."

Asked how the various sides of a religious dispute that at times was violent and political become the subject of academic gatherings, another University of Cambridge professor, Alexandra Walsham, told NCR that Luther had set out to provoke an academic debate "but confessional identities and boundaries hardened so they often became a mechanism for reinforcing difference rather than resolving it."

In a paper titled "Remembering the Reformation," Walsham argued that a Luther-centric view of the Reformation risked "overshadowing other agents, actors and aspects of the multiple and competing movements for religious reform that germinated, sprouted and grew over the course of the 16th and 17th centuries."

Luther's agendas, she said, left their mark on plans for liturgical and ecclesiastical reform in England and added legitimacy to the dissolution of the monasteries and to King Henry VIII's claim to supremacy over the church. But in the reign of his young son, King Edward VI, the nascent Church of England increasingly took its bearings from Swiss reformers such as Ulrich Zwingli and Heinrich Bullinger in Zurich, from exiled Reformers Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli, and later from John Calvin in Geneva.

English historian John Foxe's influential Book of Martyrs, published in 1563, created "an empowering patriotic narrative" that further reduced Luther's role and increased that of Queen Elizabeth I. In the two centuries after 1517, there was a systematic "forgetting of Luther," along with a distancing of the Church of England from continental Lutheran churches, Walsham said.

Nonetheless, another scholar argued that Luther had a "hidden influence on English readers" in the 16th century. Professor David Crankshaw of King's College, London, listed works by Luther that were translated into English and attributed to others such as the scholar Erasmus or the Bible translator William Tyndale.

"Similar discoveries are still being made," he added.

[Abigail Frymann Rouch is a freelance journalist in London specializing in religious affairs and was formerly online editor of the British Catholic publication The Tablet.]