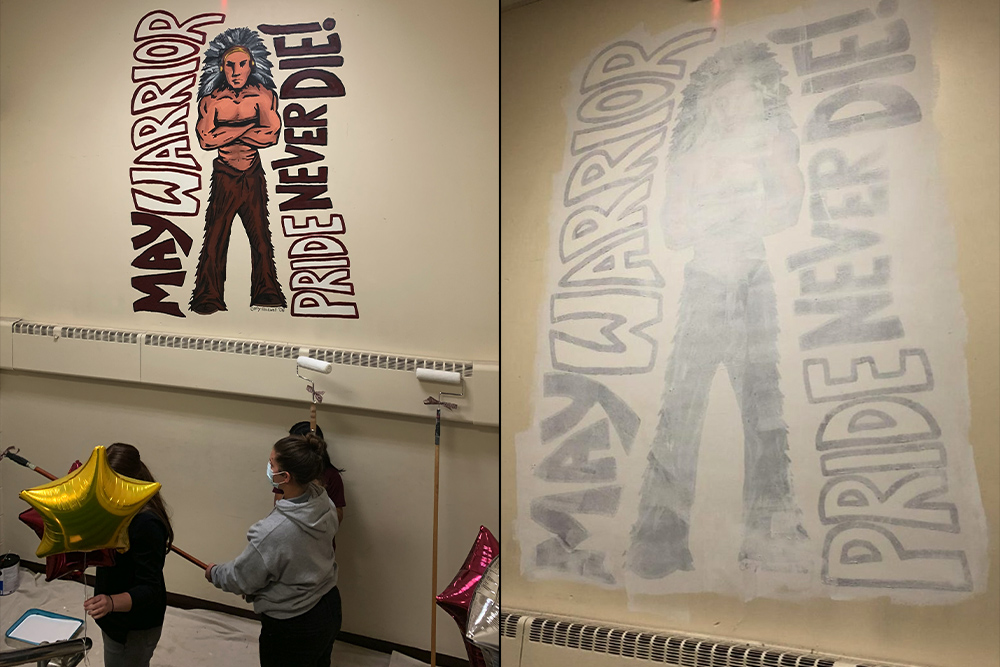

Walsh Jesuit High school in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, remains the "Warriors" but has severed its mascot's association with Native Americans. With the backing of the original artist, murals on campus were painted over in 2021. (Photos courtesy of Walsh Jesuit High School)

"Home of the Indians" is spelled out in large light blue letters across the gym wall at St. Joseph High School in South Bend, Indiana. This past February, Miriam Rios, a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, stood beneath the words to share what had long been on her heart: The school's nickname was hurtful.

"I am not a mascot or a stereotype, I am a person," the high school senior told NCR, recalling her testimony. "People have said, 'This is our tradition,' but it is a painful tradition for an Indigenous person."

St. Joseph recently conducted a monthslong process to consider a nickname change, and Rios had articulated her feelings during one of several town-hall-style meetings organized by the school. On May 2, the 70-year-old Catholic institution announced its decision. It will retire "Indians" as a mascot at the end of the current academic year.

"I was extraordinarily happy about the choice; I just wish I'd been younger so I could be at the school without the mascot," said Rios, who will attend Michigan State University in the fall.

Located a mile from the University of Notre Dame, St. Joseph is the latest non-Native Catholic high school in the United States to relinquish an Indigenous-themed nickname — part of a larger trend that's gained momentum over the past several years.

Native American Catholics, tribal leaders and educators praised the recent changes, though some noted they come decades after Native groups first brought attention to the issue. Since 1969, the National Congress of American Indians has worked for the eradication of such mascots at non-Native institutions, calling the images derogatory and harmful.

Meanwhile, at least eight Catholic secondary schools in the country continue to use Indigenous nicknames or mascots, including Antonian College Preparatory in San Antonio, known as the "Apache," and Cardinal Gibbons High School in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with the moniker the "Chiefs."

Advertisement

Percentage-wise, Catholic high schools have fewer schools with Native nicknames than their public counterparts. "But if human beings are asking us to stop doing this and saying it hurts them, and the church wants to uphold the basic dignity of all people, then change is an easy decision," said Brian Collier, a professor at Notre Dame and former senior adviser to the American Indian Catholic Schools Network.*

"It seems this should have happened a long time ago, but I'm grateful that in my own community the school has had such a good process," Collier said. "It's never too late to change."

Maka Black Elk is a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation and executive director for truth and healing at Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota**, a former boarding school. As the Catholic Church confronts new details about its role in the Native American boarding school system, said Black Elk, changing mascots also is "the bare minimum" needed to begin conversations around healing tied to such history.

'Really mixed feelings'

Fifty years ago, Native-themed mascots and logos "were ubiquitous" in U.S. schools, including Catholic ones, said Collier, whose academic work focuses on Native education. The numbers have been dropping, but according to the National Congress of American Indians, which advocates for Indigenous rights, more than 1,900 U.S. public schools still have Native-themed mascots.

Recent discussions about racism and professional sports teams' name changes likely have pushed private and public schools alike to more readily reconsider their nicknames.

In 2020, after years of advocacy and litigation from Native American groups, as well as pressure from the team's corporate sponsors, the Washington, D.C., professional football franchise announced it would drop the "Redskins" name and logo.

The pronouncement came amid protests over the killing of George Floyd and nationwide soul-searching around anti-Black racism and other forms of racial injustice. Later that same year, the Cleveland Indians baseball franchise decided to change its name.

At least 21 states have taken or are considering action to address Native-themed mascots used in K-12 public schools.

Josh Dolnia pitches during a game this season, the last St. Joseph High School in South Bend, Indiana, will be known as the "Indians." (Courtesy of St. Joseph High School/Bryant Barca)

In April, New York state education officials voted to prohibit public schools from using or displaying Indigenous team names or mascots; they included an exception for districts that obtain permission from a federally recognized tribal nation in the state.

Laws in Washington, Oregon and Connecticut have similar provisions.

State mascot bans "so far don't impact Catholic schools, but they may provide the cover for Catholic schools to make a change," said Tim Uhl, a Catholic superintendent in New York who has written about Native mascots. There have been contentious debates about nickname and logo changes, and administrators feel pressure from some alumni and others in their school communities to preserve longtime monikers.

A number of years ago, St. Joseph removed Native American images and symbols from use at the school. "There were really mixed feelings" about getting rid of the nickname entirely, John Kennedy, the school's principal, told NCR. "Many were ready for change but others found it very difficult."

Holy Cross Fr. Geoffrey Mooney is chaplain at St. Joseph and was a member of a committee charged with considering the mascot's future. "I was grateful there was not much nastiness in our process, though there were sternly worded emails here and there," said the priest.

It's not inexpensive to change out images on gym floors, locker room walls, and on uniforms and playing fields, said Collier, and some schools may resist change for that reason. St. Joseph staff will look into grants and possibly donations from the broader community to cover expenses.

In 2015, at least 15 U.S. Catholic high schools had Native-themed mascots; today there are about half that. These figures are based on a list first compiled by Notre Dame students and updated at different times by Uhl and the American Indian Catholic Schools Network, an organization housed at Notre Dame that supports Catholic schools on reservations.

Northwest Catholic High School in West Hartford, Connecticut, ended its 50-year association with the name "Indians" in 2015.

Last year, after Washington state banned the use of Native American names, symbols and images in most public schools, the former Braves of Blanchet High School in Seattle became the "Bears."

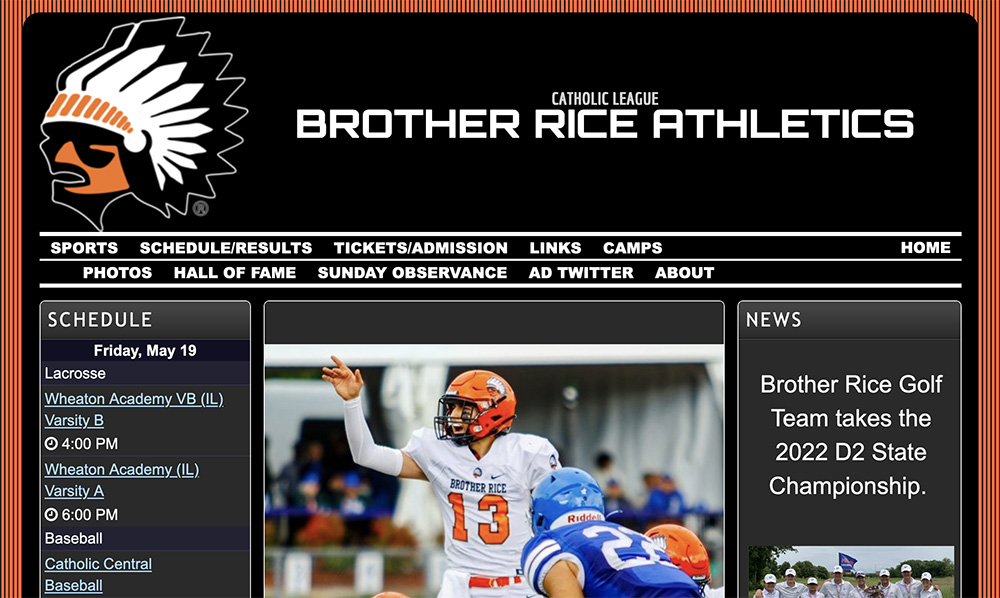

The athletics page of Brother Rice High School in Township, Michigan, includes an image of its orange-colored "Warriors" mascot. (NCR screenshot)

Yet Catholic school "Warriors," "Braves" and "Indians" persist. Brother Rice High School in Township, Michigan, has a mascot depicting an orange-skinned Indian wearing a headdress, while the athletics page of Holy Cross District High School in Covington, Kentucky, says, "Welcome to the TRIBE, the home of the Holy Cross Indians." Holy Cross school spirit gear is sold at "the Indian Hut."

Administrators at those two high schools did not respond to NCR requests for comment.

A decade ago, Brother Rice school publicly reaffirmed its use of the Warriors name and logo after the Michigan Department of Civil Rights urged a ban on Native American names and imagery in high schools.

School leaders said at the time that the Brother Rice community associated the Warrior mascot with images of strength, character and honor and did not find it racist, reported the Patch news website.

Native American groups, however, have for years contested the notion that Indigenous mascots are ultimately positive.

"Although some view Native American-themed mascots and nicknames with reverence, Native-American-themed imagery and references perpetuate harmful stereotypes," reads a statement from the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi tribal council in response to St. Joseph's decision this month. "Generations of Indigenous people have faced oppression, genocide and erasure for hundreds of years and the impacts of which can still be felt throughout our communities to this day."

Mascots with Indigenous themes, it reads, "make it hard to build meaningful and accurate relationships within the communities in which we reside."

In 2005, the American Psychological Association recommended the "immediate retirement" of such mascots based on studies that found the symbols harm Native students by negatively influencing their social identity and self-esteem.

"To have a mascot or someone dressed up in a headdress who's not Native American — they are wearing them as a costume, and they are not a costume, they are sacred regalia used in traditional dancing," Rebecca Richards, tribal chairwoman of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, said in a recent interview with NCR.

Rios, the senior at St. Joseph, said mascots are often animals, and "it's belittling to be put in the same category as animals."

The mascot at Mahpíya Lúta-Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota**, features Lakota Sioux chief Mahpíya Lúta, who led several victories against the U.S. military. (Courtesy of Mahpíya Lúta-Red Cloud Indian School)

Mascots at non-Native Catholic schools "implicitly tell non-Indigenous kids that these communities are not real, they are disposable, cartoonish," said Black Elk, of Red Cloud Indian School (more recently called by the Lakota term for Red Cloud, "Mahpíya Lúta"). "They hurt their ability to have relationships that are healthy and meaningful with Indigenous people."

Richards added that Native American boarding schools in the United States — more than 20% of them run by Catholic institutions — "caused historic trauma" that many Indigenous people still grapple with.

"Moving away from mascots can be a step in a healing process," she said.

A question of Catholic identity

Several Catholic high schools that have had Native-themed mascots told NCR they opted to keep their nickname but reduced or cut its association with Native Americans. In Hammond, Indiana, for example, Bishop Noll High School abandoned its headdress logo but remains the "Warriors" in a general sense of the term.

"Being called the Warriors doesn't necessarily mean an entity is Native-themed," said Paul Mullaney, Bishop Noll president. He said the school hopes graduates are "warriors for peace, warriors for social justice, warriors for the sanctity of life."

In 2011, Justin-Siena High School in Napa, California, longtime home of the "Braves," received support from the Mishewal-Wappo Tribe to create a new mascot and logo depicting a Native person in a headdress. The school has since stopped using the image and now only utilizes the school seal and shield for branding, though it's kept the Braves nickname.

Calvin Hedrick, a community organizer and member of the Mountain Maidu in California's Sierra Nevadas, said many tribal people were "very, very upset" when Justin-Siena adopted the now-abandoned mascot image. He said he's observed other instances when non-tribal communities hope for approval from a tribe about a specific matter and "will keep asking until they find someone who signs off."

The new mascot for Walsh Jesuit features a superhero-style warrior rather than a rendering of a Native American warrior. (Courtesy of Walsh Jesuit High School)

Walsh Jesuit High school in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, recently changed its mascot from a Native American warrior to a superhero-type image that looks akin to a medieval soldier. The artist who originally painted images of Native Americans around the campus supported the change, and the school held a ceremony to paint over the former images at her request.

The changes "were not political correctness but Jesuit justice," said Karl Ertle, president of the Midwest school.

At St. Joseph, a nickname evaluation committee read studies, held town-hall-model gatherings, conducted a survey and consulted with the local Pokagon Band of Potawatomi. Speaking with members of the band, they learned it had issued a resolution in 2021 condemning the use of Native themed imagery, symbolism and nicknames by non-Native institutions, stating they have "a detrimental effect on Native Americans."

"The testimony and opinion of the tribe — that was key to the whole process," said Bishop Kevin Rhoades of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Indiana. Rhoades said he felt the school's approach was commendable and he was "very happy with the outcome."

"It was what I'd hoped for," he said.

"At the end of the day, the most important thing was alignment with the mission and core values and our Catholic identity," said Kennedy, the principal. "If this was harmful to one human being then it does not align with that identity."

Many Native Americans say Native-themed mascots at schools serving predominantly Indigenous children are not typically problematic.

The three Native Catholic high schools in the United States, all located on reservations, are St. Michael Indian School in St. Michaels, Arizona; Red Cloud-Mahpíya Lúta; and St. Labre High School in Ashland, Montana.

Mascots at non-Native schools are one dimensional, said Curtis Yarlott, executive director of the St. Labre Indian School. "Here at St. Labre, where more than 90% of students are Indigenous, saying, 'We are the Braves' actually represents our student body." And the concept of what a brave is has depth.

"A brave is someone who is a protector and defender of people, who puts the community before himself and has a particular creed of honesty and integrity," Yarlott said.

While most advocacy groups and many Native people oppose mascots at non-Native schools, Yarlott said he does not feel they are wrong in every instance.

He believes it's important for a non-Indigenous school to help students, staff and the broader community "understand the qualities embodied by the mascot." He said it's also critical to listen to local Native voices and take concerns they have to heart.

After listening to personal accounts of Native people, Mooney, the chaplain at St. Joseph, said he feels "a sense of conversion in my own heart that this is the direction we need to go in Catholic schools."

He said he "shudders in regret and horror" as he recalls being at other schools with Indian-themed days or playing teams with Native mascots who said or did inappropriate things.

"During this process we've heard, 'My people are not logos, we are individuals, we are human beings,' " said Mooney. "At a Catholic school, we must be sure we are recognizing that every person is created in the image and likeness of God and we must be sure every person is treated with dignity."

*This article has been edited to correct Collier's current status with the network.

**The article and caption have been edited to correct the state where Pine Ridge is located.