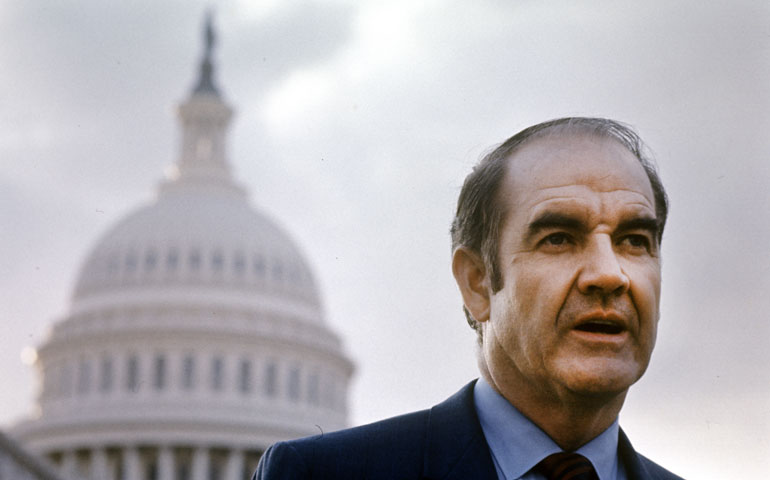

Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota in 1972 (Newscom/ZUMA Press/Photoshot)

On the Wednesday afternoon in early November 1972 after his defeat the day before by Richard Nixon for the presidency, George McGovern and his wife, Eleanor, arrived at Washington's National Airport. The loss had been nearly total, with McGovern, a liberal populist Democrat from South Dakota, winning only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

By chance, his running mate, Sargent Shriver, was arriving at the same time from another plane. They came upon each other in the main concourse. Seeing a dejected McGovern, with his wife in tears about losing even their home state, Shriver offered a powerful consoling line: "George, we may have lost the election, but we certainly didn't lose our soul."

Within three years, Nixon, a scheming and deceitful politician who spared nothing in his depiction of McGovern as an unpatriotic ultraliberal, would resign in disgrace over the Watergate scandal.

At his death in late October, McGovern remained in full possession of the soul-force that marked a political career that began in the House of Representatives in 1956 and ended in the Senate in 1980. I recall a conversation once when he laughed about Republicans' portrait of him as a wild leftist, wondering how he managed to win House and Senate races in South Dakota, one of the country's most conservative states. His liberalism knew a boundary or two. He had little regard for the showmen of the 1960s anti-war movement -- from Abbie Hoffman to Jerry Rubin -- and saw them as ineffectual clowns.

McGovern's passions ranged from opposition to the Vietnam War to advocating for nutrition programs for the hungry in this country and abroad. He advocated for small farmers as they saw their lands swallowed by corporate agribusiness. He stood with the tribal nations, a stance so firm that the Oglala Sioux of South Dakota called him "the Great White Eagle."

McGovern first visited South Vietnam in late 1965, a visit that confirmed his hunch that the war was doomed. The year before, he voted in favor of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave a pass to President Lyndon Johnson to escalate the war after an attack by North Vietnam on an American patrol boat -- an attack that never happened. It was a vote McGovern would eventually be ashamed of, missing the chance to join Wayne Morse and Ernest Gruening as the only two members of the Senate to say no.

Perhaps to compensate for the lapse, McGovern became the strongest anti-war voice in the Senate. His military record of personal bravery -- he flew more than 30 high-risk bombing missions in the Second World War -- gave him credibility. In a Sept. 1, 1970, floor debate on his amendment, co-sponsored with Mark Hatfield, to end the war, McGovern said:

Every senator in this chamber is partly responsible for sending 50,000 young Americans to an early grave. This chamber reeks of blood. Every senator here is partly responsible for that human wreckage at Walter Reed and Bethesda Naval [hospitals] and all across our land -- young men without legs, or arms, or genitals, or faces, or hopes. There are not very many of these blasted and broken boys who think this war is a glorious adventure. Do not talk to them about bugging out, or national honor, or courage. It does not take any courage at all for a congressman, or a senator, or a president to wrap himself in the flag and say we are staying in Vietnam, because it is not our blood that is being shed. But we are responsible for those young men and their lives and their hopes.

The grandson of Irish immigrants and the son of a Methodist pastor, McGovern suffered tragedy in his personal life. The story is told in Terry: My Daughter's Life-and-Death Struggle With Alcoholism. Published in 1996, two years after Teresa McGovern, 45, froze to death in a snowbank in Madison, Wis., after a night of drinking, it is the most soulful of his half-dozen books: a lovingly written work blended with self-therapy and spirituality.

My last visit with McGovern came a few years ago when he spoke on a Sunday afternoon to a small gathering at a civic center in the Friendship Heights neighborhood of Chevy Chase, Md. I brought Shriver to the talk. It was a touching reunion of the two former running mates. Shriver, sinking slowly into Alzheimer's disease, had no memory of McGovern, much less of their campaigning decades ago. But the two, both giants of service and goodness, embraced each other with deep affection, leaving me and other onlookers to wonder what kind of country we might have become if the election of 1972 had gone the other way. A more humane country? A country at peace with the world? A country loved globally for its generosity, not hated or feared for its belligerence?

Little time was needed for wondering about the obvious answers to those questions.

[Colman McCarthy directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington and teaches courses on nonviolence at four universities and two high schools.]