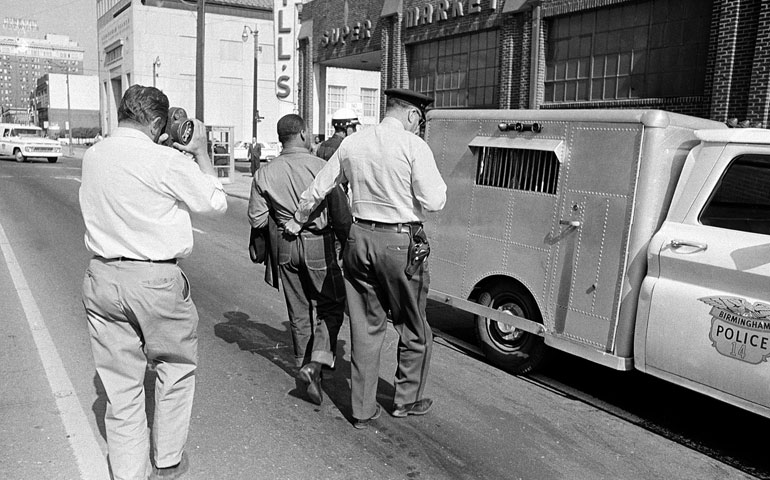

A police officer leads the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. away after his arrest in Birmingham, Ala., on April 13, 1963. (AP)

"We must become troublemakers for the beloved community." So Congressman John L. Lewis (D-Ga.) invited members of the ecumenical group Christian Churches Together to enact a new response to Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail."

Acting on their declaration to become "extremists for love, justice, and peace in Christ" will be no easy task for Christian Churches Together members, who gathered April 14-15 in Birmingham, Ala., to commemorate the 50th anniversary of King's letter. It will be no easy task because white norms and culture still dominate many churches. Or, to rephrase Jesus in Mark 10:25, it may be easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for white people to enter the kingdom of God. One of the crises of our day is that predominantly white churches may not recognize this moral and spiritual peril.

Recall that King wrote his letter in April 1963 in response to a statement signed by two Episcopal bishops, two Methodist bishops, one Presbyterian minister, one Baptist pastor, one rabbi and one Roman Catholic bishop.

In their statement, these eight white clergymen appealed to "law and order," called the nonviolent protests against Jim Crow laws "extreme measures" and demanded an end to demonstrations. They asserted that outside agitators had come to Birmingham to create racial disorder.

In his response, King expressed full respect to the clergymen and immediately conveyed how "injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny."

The Birmingham struggle was far from being created by extremists outside the city, King explained. Local leaders had issued to King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference a "Macedonian call for aid" (Acts 16), he wrote.

He expressed sadness that the eight clergymen did not demonstrate similar concern for the injustice that led to the demonstrations, including the use of violence by the police against innocent, nonviolent demonstrators. He elucidated the four basic steps of nonviolent protest: collection of facts to determine if injustice is occurring; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action. The letter details how civil rights activists were faithful to nonviolence through every step.

Citing Sts. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, he proclaimed "an unjust law is no law at all." Recall that the Jim Crow South used lynching, police violence, denial of the right to vote, and denial of educational resources to enforce a culture of injustice.

"It is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily," King stressed, saying that "freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."

The Rev. Bernice King, daughter of Martin and Coretta Scott King, emphasized this point in her speech at Christian Churches Together's conference: The sacrifice for freedom must be waged every day by every generation. While the civil rights movement broke down many barriers, we have yet to engage a deeper transformation of the soul of America.

As I walked the streets of Birmingham for a mile or so between my hotel and the conference site, I was struck by memory of the witnesses who presented their bodies (Romans 12:1) as worship to God and for the transformation of society.

Birmingham is as hallowed as any place upon which the struggle for humanity has been waged. On this ground, half a century ago, thousands sacrificed their bodies and livelihood for freedom, justice and, ultimately, the unity of the human family before God.

I noticed the empty, crumbling stores that were once graced with nonviolent civil rights activists. I felt a humble trembling through my soul as I walked these holy streets. Humility is rooted in the Latin word for earth, humus. This earth echoes their cry for justice. Their witness to the beatitude calls us to walk similarly: "Blessed are the meek, they shall inherit the earth" (Matthew 5:5).

I clearly remember that in his time King and nonviolent activists within the civil rights movement were pejoratively named troublemakers. Except for Maryknoll sisters who told my family about their experience of walking in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery, adults in our lives -- parents, family, teachers and religious leaders -- did not acknowledge the Gospel insight of the civil rights movement.

Dorothy Cotton, who served as director of the Citizenship Education Program for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, reminded conference participants that civil rights activists were far from revered during the height of the struggle for freedom. Conversely, she also expressed concern that we have idolized King in death, creating an idol far removed from the man she knew.

We have forgotten who he really was and the very meaning of the nonviolent civil rights movement. We have effectively sanitized King and the civil rights movement of their prophetic Gospel witness. Denigrating their witness when they lived and worshiping a false idol today, we obfuscate the core spiritual witness of "Letter from Birmingham Jail" and of civil rights activists.

Pastor Virgil Wood, who served the board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference during the last 10 years of King's life, commended the leaders for their statement and, without cynicism, issued a healthy word of warning. The new response is "only a start" that calls leaders to become "doers of the word."

Wood rightly invites us to pause and reflect. White churches have yet to take the core message of "Letter from Birmingham Jail" into prayer and mobilization for justice.

King confessed in his letter that his greatest disappointment was not with the Ku Klux Klan or the White Citizens' Councils but with the "white moderate, who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, 'I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can't agree with your methods of direct action'; who paternalistically believes that he can set the timetable for another man's freedom."

"Shallow understanding from people of good will," King said, "is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will."

White evangelical leaders Ron Sider and Jim Wallis reminded conference participants that white churches got the race question wrong during the civil rights movement and have yet to get it right today.

Catholic Archbishop Joseph Kurtz of Louisville, Ky., expressed sorrow for the way U.S. Catholic bishops originally responded to King's Letter. He stressed the need for building programs of restorative justice within Catholic Charities USA.

Auxiliary Bishop Shelton Fabre of New Orleans called on participants to remember our collective past as a way to overcome historical ignorance and enact good public policy. More importantly, he said, the sacraments call us to "engage conversion of human hearts in racial harmony," so as "to transform attitude and action in ourselves and others."

The Rev. Sharon Watkins, general minister and president of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), reminded us that Jesus' last prayer was for the unity of all people in God. She called us to "pray for unity every day with our feet, hearts and hands."

Watkins lamented, however, that "the sin of racism runs deep in our church" as "the seductive power of white privilege" closes our eyes to the reality of hyper-incarceration of people of color.

Lisa Sharon Harper, Sojourners' director of mobilizing, underscored how our churches have a "separation problem" both in terms of geographical segregation and from the Gospel. The problem of separation creates "fertile ground for White Citizens' Councils" and movements that deny the rights of new immigrants.

The price of freedom, Lewis, Cotton and Wood emphasized, is not only eternal vigilance. More deeply, the price of freedom is ongoing struggle. Nonviolent struggle demands, as these civil rights leaders teach, training and self-purification.

As a form of violence, the work and struggle of undoing internalized white superiority and racism is no different. Many people of color and whites have taught for centuries that ending racism will demand a different kind of training of our bodies, minds and souls.

And, if we are to become "troublemakers for the beloved community," as these diverse churches committed themselves on April 15, then that will demand training people of faith in the way of nonviolence and anti-racism.

No doubt it will demand an intensive struggle for good people who have accepted the benefits of whiteness for too long. Such a struggle would demand relinquishing power and advantages with which we have become too comfortable.

The work of becoming anti-racist demands self-purification of the idols of power, privilege, control and innocence that imprison white Christians from our recognizing our common humanity as children of God. By engaging a struggle to become troublemakers with Jesus, we may yet glimpse the infinite possibilities of his final prayer for unity.

[Alex Mikulich is co-author of The Scandal of White Complicity in U.S. Hyper-incarceration: A Nonviolent Spirituality of White Resistance.]

Conference commemorates 50th anniversary

Leaders from Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox and evangelical traditions gathered April 14-15 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in Birmingham, Ala. Christian Churches Together organized the event not only to commemorate King's historic letter but also to correct the failure of these churches ever since to become collaborators in its Gospel message.

Released through a formal signing ceremony, these leaders committed their churches to live, pray and enact the letter by:

- Realizing our interdependence;

- Addressing the root causes of injustice;

- Engaging the struggle personally;

- Seeking a higher standard for public policy and political participation;

- Becoming extremists for Christ's love, justice and peace;

- Acting now;

- Engaging nonviolent direct action as a strategy for social transformation;

- Challenging injustice by bringing it to light;

- Cherishing the church while holding it to a higher standard;

- Holding fast to the true foundation of the American dream.

The full text of Christian Churches Together's "A Response to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'Letter from Birmingham Jail' " and individual statements from each participating faith tradition are available online.

-- Alex Mikulich