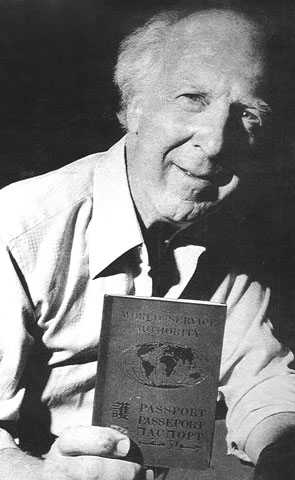

Garry Davis in 1988 holds a passport issued by the World Service Authority. (AP file photo)

Fewer rebels had grander visions for disarmament and world peace than Garry Davis, and fewer still of these dissidents acted as practically, emphatically, spiritually, personally and -- while we're at it -- morally to show the way.

It began on May 25, 1948, when the 26-year-old former Broadway actor and B-17 bomber pilot in World War II walked into the American embassy in Paris to renounce his U.S. citizenship and claim world citizenship. Stateless and believing the planet should be borderless, he became an Earthian.

Garry Davis would keep that for the rest of his long and stellar life, one that ended peacefully at age 91 in late July in South Burlington, Vt.

His conversion from nationalism to globalism, from militarism to pacifism, is traceable to his feelings of profound remorse at the war's end in August 1945. "Ever since my first mission over Brandenburg, I had felt pangs of conscience, and, underneath all the grief, emotionalism and propaganda-nourished hatred, I had begun to question the morality of punishing the German people with our superior firepower," he later wrote. "How many bombs had I dropped? How many men, women and children had I murdered? Wasn't there another way, I kept asking myself."

With no passport and no regard for nation-state borders, Davis became a relentless gatecrasher. By one government or another, he would be arrested and jailed more than 20 times for being undocumented, not to mention unwelcomed. Among those taking notice was Eleanor Roosevelt, easily the most politically progressive of the nation's first ladies. Instead of giving speeches promoting world citizenship, she said in her newspaper column in December 1948, "how very much better it would be if Mr. Davis would set up his own governmental organization and start then and there a worldwide international government."

He did exactly that, creating the World Government of World Citizens. Its administrative office, the World Service Authority, a nonprofit based in Washington and few blocks from the White House, began issuing passports to refugees, deportees and others among the teeming unwanted and unpapered. By last count, nearly 1 million people are registered and more than 500,000 carry WSA passports granted for modest fees well below what governments demand. Printed in seven languages, from Chinese to Esperanto, the passports are accepted in Burkina Faso, Ecuador, Mauritania, Tanzania, Togo and Zambia. On a case-by-case basis, more than 100 countries have honored the passports over the years.

I came to know Davis when he was a neighbor in Washington, welcoming him in my home and classrooms. Despite the gravity of his defiance of governmental power, he was ever cheerfully optimistic that his ideas and ideals on world government would eventually be seen as sane and not, as he quipped, "out of this world." He has credibility on that. His 1948 stand in Paris as a world governmentalist drew praise from Albert Einstein, Buckminster Fuller, John Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, E.B. White and Albert Schweitzer. "I feel compelled to pay my respects to Mr. Davis," Einstein said, "the youthful war veteran, for the sacrifices he has made for the general welfare of mankind."

Art Buchwald, the newspaper columnist who lived in Paris in his student days, said, "I always thought of Garry as Jesus Christ without a tourist visa."

Davis "shall always be remembered by those who were witness to his grand gesture," Buchwald wrote. "His vision of world government was slightly premature, but some of it is actually happening. ... Europeans are no longer required to carry passports to visit one another. I pray that someday the Hôtel des États-Unis will be renamed the Garry Davis Ritz."

Davis' books, which included My Country Is the World: Adventures of a World Citizen, World Government, Ready or Not! and Passport to Freedom: A Guide for World Citizens, are a blend of piquant personal stories, karmic insights, and calls for deliverance from the rut of military violence.

"Patriotism or love for one's country is totally dependent on love for one's planetary community," Davis said. "How can the part survive without the whole?"

Davis ran for U.S. president in 1988. Had he won, he would have become the only president in modern times to end speeches not with the false piety of "God bless America" but with a rousing "God bless the whole world."

[Colman McCarthy directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington and teaches courses on nonviolence at four universities and two high schools.]