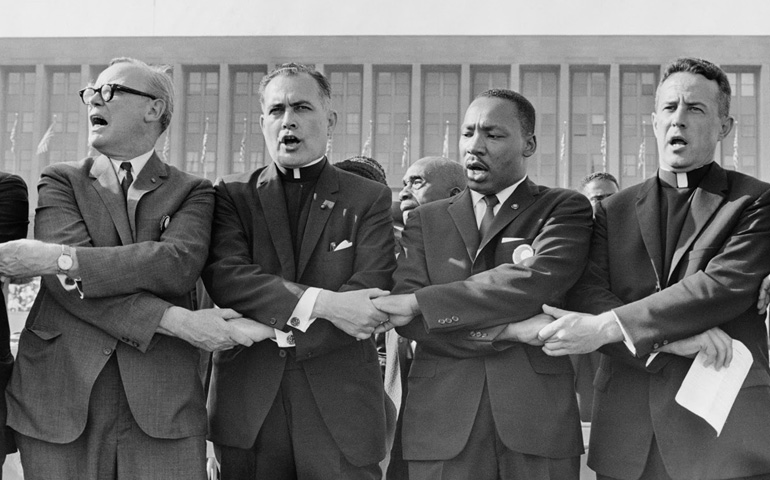

Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh, second from left, joins hands with the Rev. Edgar Chandler, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and Msgr. Robert Hagarty of Chicago in 1964 at the Illinois Rally for Civil Rights in Chicago's Soldier Field. (CNS/courtesy University of Notre Dame)

Retired U.S. Sen. Harris Wofford (D-Pa.), who will turn 89 on April 9, met Holy Cross Fr. Ted Hesburgh in 1957 at the birth of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in Washington, D.C. The White House brought Wofford's name to Hesburgh's attention. Wofford was a young attorney in private practice, and Hesburgh recruited him to serve as legal counsel at the commission. They quickly became kindred spirits, global citizens and two public servants dedicated to the plight of African-Americans, to the poor, the young, to public service and to the common good.

After four years at the commission, Wofford left to become a law professor at Notre Dame.

Wofford was an early believer in, and friend of, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Later, both Hesburgh and Wofford participated in the civil rights movement.

Wofford moved on to the Kennedy presidential campaign and personally encouraged John F. Kennedy to call Coretta Scott King after her husband was imprisoned shortly before the 1960 election. News got out that Kennedy made the call. King then switched his endorsement to Kennedy from Nixon. Kennedy went on to beat Nixon by a small margin that has been attributed to the African-American vote. Wofford was appointed special assistant to the president on civil rights.

Hesburgh's work at the Commission on Civil Rights laid the foundation for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Later, both Hesburgh and Wofford played major roles in the creation of the Peace Corps. Wofford wrote the book Of Kennedys and Kings: Making Sense of the Sixties, which describes his work in the civil rights movement and the creation of the Peace Corps.

Wofford went on to become president of State University of New York at Old Westbury and later at Bryn Mawr College.

In the early 1990s, Wofford was appointed by Pennsylvania Gov. Bob Casey, a Democrat, to fill the vacant U.S. Senate seat after John Heinz died in a plane crash. Six months later, Wofford beat former Pennsylvania Gov. Dick Thornburgh for the seat. Four years later, Rick Santorum defeated Wofford, who has dedicated his subsequent years to promoting public service.

In 2011, the Peace Corps created the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award. In 2012, President Barack Obama awarded Wofford the Presidential Citizens Medal, which recognizes "exemplary deeds or services for his or her country or fellow citizens."

This week, Wofford traveled to South Bend, Ind., to attend the wake service and funeral Mass for his good friend Hesburgh. Just prior to the funeral service, Wofford spoke with NCR by telephone and shared a wide-ranging perspective of him. The interview was edited for space and organization.

On the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

Father Hesburgh was a major factor in my life and in the life of the country. I was a young lawyer in Washington, D.C., at Covington & Burling LLP, and [Dwight D.] Eisenhower was president. I wrote a memo about the creation of the civil rights commission, which the White House had. The first commission had three Southern members and three Northern members. Each commissioner was to have his own legal counsel.

Father Hesburgh came out of a White House meeting and called me at the law firm on the telephone out of the blue. He said he had read my memo and liked it, and he offered me a job working as his counsel at the commission. He said that I'd be making less money, but I would be making an important contribution to the country. So I signed on.

The commission met with President Eisenhower, who didn't think this diverse group of commissioners would ever be able to agree on anything. Any yet the commission was unified, very bold and comprehensive in its fact-finding and recommendations.

Eisenhower was surprised how the commission worked so well together. Father Hesburgh explained to Eisenhower "that we [commissioners] are fishermen." Eisenhower replied, "If that's what it takes, then find fishermen for the rest of my administration." Eisenhower accepted the votes and work of the commission.

Father Hesburgh had a major role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The work of the commission provided the essential ingredients.

On leadership

Father Hesburgh was the wisest, most effective person I had the great luck to meet and work with for some 58 years and right to the end. Father Hesburgh could take any problem and find a just solution. He was the most effective person in public life and skilled at all the vital issues of the day. He always gave good advice and in finding ways to solve problems.

Understanding President John F. Kennedy

I became aware of Kennedy and like[d] him because of his foreign policy speeches while in the U.S. Senate. The key to understanding Kennedy was understanding that he was interested in world affairs and peace. His inaugural speech was all about human rights around the world, and we convinced him to add something about human rights at home.

Father Hesburgh believed deeply in peace. He had the ability to be deeply involved in a problem and solve the problem. He could work with Republicans and exchange humor, and both would be determined to advance the common good.

Hesbugh's example

We had Mass every morning, countless Masses, in hotel rooms, everywhere we went. [Hesburgh's] goodness spilled over readily. Over time, Father Hesburgh's example prompted me to convert to Catholicism from being an Episcopalian.

Father Hesburgh had well over 100 honorary degrees that reflect his dedication to God, country and Notre Dame.

Today, Pope Francis conveys a real magnetism. Yet Father Hesburgh had the same magnetism. I wish the church realized what it had with Father Hesburgh. Father Hesburgh could have been pope.

Fr. Hesburgh and the Soviet nuclear scientist

We shared many beliefs, like the need for world peace and to avoid nuclear war. Father Hesburgh was the pope's representative on the International Atomic [Energy] Agency, which reminds me of a story. Father Hesburgh became friends with a Soviet scientist, and when they met, Father Hesburgh warmly greeted the scientist. At that point, a fellow from the U.S. State Department whispered in Father Hesburgh's ear, saying that we don't take pictures with the Russians. Father Hesburgh said, "We get instructions from different authorities" [and took the pictures].

On public service

Father Hesburgh also believed that the academic institution should involve itself in civil duties and encouraged the engagement by faculty and students [in public life], that higher education should be on the front lines [of major issues of the day].

On the Peace Corps

Sargent Shriver wanted Father Hesburgh to be a part of the early planning session for the Peace Corps. As a result, Notre Dame was the first university associated with the Peace Corps program. Shriver permitted Notre Dame to administer the Peace Corps program in Chile, which was the only country that Shriver ever allowed another organization to administer.

On leading a university

When I was at Bryn Mawr [as president from 1970-78], I had Father Hesburgh come to be the commencement speaker. I'd like to think that I did follow Father Hesburgh's example of a university president. I think he recognized that I was on his trail.

On impacting the lives of young people

No one has impacted the lives of young people like Father Hesburgh. He took seriously every person who came to him, who needed help and light, at any hour of the day or night. That's thousands of Notre Dame students over the years. That's Notre Dame. And he did this all over the world.

On staying in touch

Father Hesburgh not only listened to people and especially to their problems, but he kept track of them. About nine months ago, he called me and said, "We haven't talked in a while, what are you up to?" We had a good talk. I told him that I'm working on a way that every student would have a right to serve [the poor] around the world. He immediately asked, "What can we do about it?" I said, "I would love it if you would write an op-ed about it." He said he would love to do so.

Most people avoid adding something to the schedule, to their responsibilities. Not Father Hesburgh. He was ready to immediately help.

Father Hesburgh was a fisher of men, a fisher of women, a fisher of the young and of the old. He was courageous, compassionate and creative. He was a giver of life.

[Tom Gallagher is a regular contributor to NCR. He can be reached at tom@tomgallagheronline.com.]