Robert Deeley, left, Bishop of the Diocese of Portland, Maine, accompanied by Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston and president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, speaks during a news conference at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2019 spring meetings in Baltimore, Md., Tues., June 11, 2019. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

In response to recent accusations of episcopal misconduct, the U.S. Catholic bishops have adopted a process for reporting and investigating allegations of sexual misconduct and coverup by bishops.

The directives adopted overwhelmingly by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops at their meeting this week in Baltimore, Md., implement the papal apostolic letter "Vos estis lux mundi" ("You are the light of the world"), issued after the summit on clergy sexual abuse convened by the pope in Rome in February.

The bishops also voted to affirm their commitmentto be covered by the 2002 Dallas Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, which many people complained applied only to priests and not bishops.

Another document laid out the power that a diocesan bishop has for dealing with a retired bishop living in his diocese if he was involved in misconduct. For example, the diocesan bishop can refuse to let him do priestly work in the diocese.

Critics have questioned the new system because it involves bishops investigating bishops, but the bishops have promised to involve lay experts in the process, just as they already involve the laity in the process of investigating priests.

"Lay involvement should be mandatory to make darn sure that we bishops do not harm the church in the way bishops have harmed the church, especially what we have become aware of this past year," said Bishop Shawn McKnight, bishop of Jefferson City, Mo.

Bishop Robert Deeley of Maine, chair of the U.S. bishops' conference Committee on Canonical Affairs, responded that the bishops’ conference could not mandate lay involvement but could strongly encourage it.

In response to a question from Jack Jenkins of Religion News Service, Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark noted that at a meeting of archbishops this week the question was asked, "Does anyone here believe that you can do justice to what the church expects of us or what civil society expects of us without using qualified lay people?" No archbishop believed that, according to Tobin.

Deeley added that, "In every single diocese of the United States you have a review board that is made up predominately of laypeople. So we have already fulfilled that commitment."

The system adopted by the bishops is not a perfect system — no system is — but it represents huge progress over the past, when episcopal misconduct was either ignored or covered up. In the past, only Rome was involved in the investigation of bishops, and the process was surrounded by secrecy.

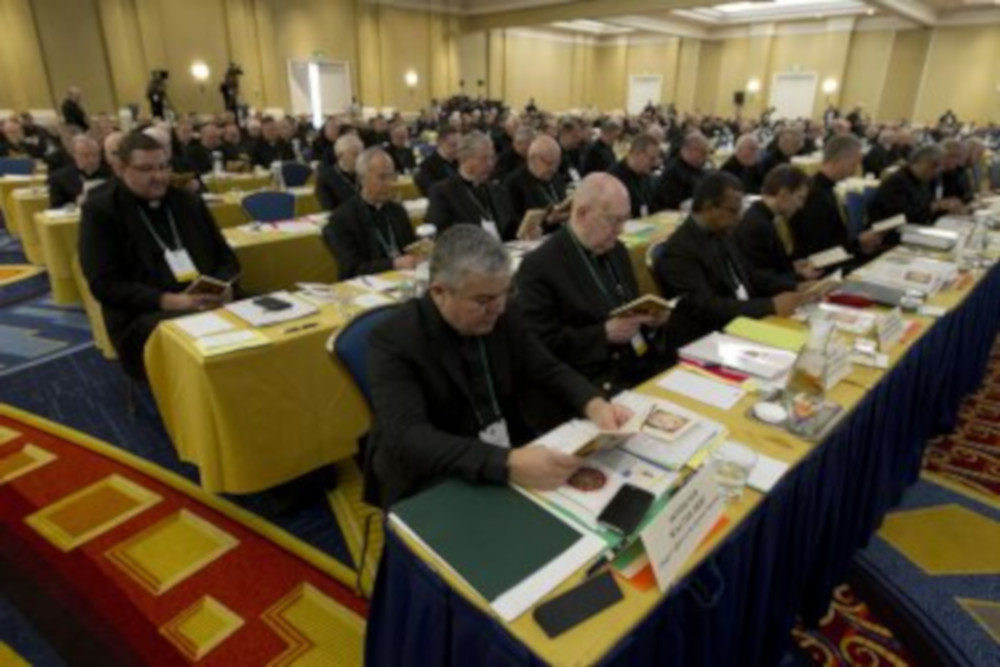

Catholic bishops participate in a morning prayer June 11, 2019, during the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ spring 2019 meetings in Baltimore. (AP/Jose Luis Magana)

The key figures in the new way of doings things will be the United States’ 32 metropolitan archbishops. They will now be responsible for receiving allegations against bishops in their provinces. Also receiving the allegations will be a lay person to help the archbishop. If the allegation is against the archbishop, then the senior bishop in the province will be responsible for dealing with it.

Allegations can come to the metropolitan from any source, including a national hotline and website for reporting allegations against any bishop, which will be run by an independent company the bishops' conference will hire. This system must be in place by June of next year, but the bishops hope it will be up and running earlier.

If the allegation is of sexual abuse of a minor, the archbishop must immediately report it to civil authorities.

The metropolitan will report all allegations to the nuncio, the pope’s representative in the United States, and then wait for Rome to empower him to do an investigation.

Bishops complained that according to “Vos estis,” Rome could take up to 30 days before responding, much longer than people in the United States are willing to wait. Los Angeles Archbishop Jose Gomez, the U.S. bishops' conference vice president, said that from his visit to Rome he is convinced that “the Holy See is aware of the urgency of these matters and obviously they are responding as fast as possible to specific situations in the United States.”

Once he receives authorization from Rome, the archbishop will investigate the allegations using lay experts. Lay experts will also be involved in evaluating the evidence and on the metropolitan’s report to Rome.

Deeley, chair of the bishops' conference committee that developed the directives, said he was confident the process would work. He noted that similar processes were used successfully in investigating four U.S. bishops in the last year, including Theodore McCarrick and West Virginia Bishop Michael Bransfield.

The lay groups that advise the bishops' conference, the National Review Board and the National Advisory Council, argued strongly this week for robust involvement of laity in the process.

Deeley said the directives provide for collaboration with laity in three ways:

- “Through the stable appointment of a layperson to receive reports against bishops and to assist the Metropolitan with the initial assessment of the report.

- “By providing indispensable expertise in the investigative process overseen by the Metropolitan.

- “Through assistance to the Metropolitan in the assessment phase prior to the submission of his votum (opinion) to the Apostolic See that is sent with the acts of the investigation.”

How well this all will work, of course, is still a question. The laity and the media will have to keep watch to make sure the metropolitans and the Holy See responsibly implement the system, which has no provisions providing for transparency.

Transparency is especially important to the review board and the advisory council — and not only on cases going forward. They called for full disclosure of the facts surrounding the scandal involving Theodore McCarrick, the former cardinal who lost his red hat and was removed from the priesthood after being being investigated for abusing an altar boy and sleeping with seminarians.

Advertisement

The National Advisory Council has repeated its call for an independent entity to engage in a thorough investigation into how the allegations, which had been circulating for years, were handled both here in the U.S. and at the Vatican.

The National Review Board also recommended that the audits of dioceses mandated by the Dallas Charter be more thorough and independent.

"Auditors should have the independence to ask the questions that need to be asked, examine the documents they determine need to be examined and probe where they feel they need to probe to answer the questions, resolve the issues and determine compliance," said the board, adding that the audit process should be designed by the outside auditors, not the bishops.

It also said all allegations of sexual abuse of minors should be reported to diocesan review boards, with no prior screening by the bishop or his staff.

The fact that the National Review Board still finds problems with the implementation of the Dallas Charter after 17 years should give us pause about putting full faith in the bishops’ new system for dealing with episcopal misconduct. The Dallas Charter has been well, but not perfectly, implemented. Perfection should be our goal when it comes to the protection of children.

[Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.]

Editor's note: You can sign up to receive an email every time a new Signs of the Times column is posted. Sign up here.