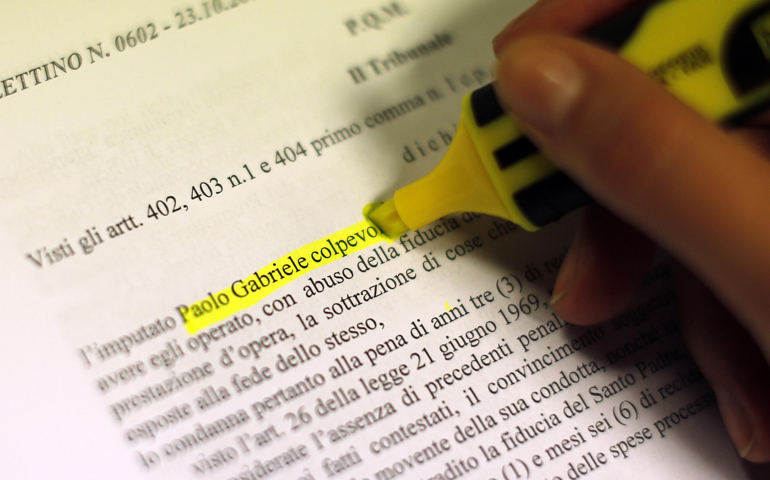

A journalist highlights the sentence "Paolo Gabriele guilty" as the Vatican spokesman, Jesuit Fr. Federico Lombardi, talks to reporters about the sentence of Pope Benedict XVI's former butler, Paolo Gabriele, on Tuesday at the Vatican. (CNS/Reuters/Alessandro Bianchi)

Claudio Sciarpelletti, the Vatican Secretariat of State computer technician accused of aiding and abetting the pope's butler in stealing confidential Vatican correspondence, will go on trial at the Vatican on Nov. 5.

The Vatican announced the trial date Tuesday. Jesuit Fr. Federico Lombardi, Vatican spokesman, told reporters Sciarpelletti's trial on the "minor charges" of aiding and abetting was expected to be brief.

Also on Tuesday, the Vatican released a 15-page document from the three-judge panel that found the butler, Paolo Gabriele, guilty Oct. 6 and sentenced him to 18 months in jail.

After criminal trials in Italy and at the Vatican, the judges publish a detailed explanation of how they arrived at their verdict and how they determined the sentence. Lombardi said a Vatican prosecutor will study the document and has 40 days to decide whether he will file an appeal, something usually done to request a harsher sentence.

Gabriele, who also had a chance to appeal his conviction, declined to do so; he remains under house arrest until the prosecution decides about its appeal, Lombardi said. Pope Benedict XVI also could pardon his former butler.

Lombardi said if the pope does not pardon the 46-year-old Gabriele, Vatican judicial officials plan to have him serve his sentence in a 12-foot-by-12-foot cell in the Vatican police barracks and not in an Italian prison.

The report included the fact that the judges denied a request by Gabriele's lawyer to have retired Cardinals Ivan Dias, former prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, and Georges Cottier, former theologian of the papal household, testify before a papally appointed commission of cardinals conducting a separate investigation of the leaking of Vatican documents.

The judges said it was beyond their powers to do so; there was no explanation of what kind of information the defense thought the two cardinals could provide.

In the judges' report, they said while Gabriele consistently maintained he acted out of love for the pope and the church, the judges felt an obligation "to observe how the action undertaken by Gabriele in reality was harmful" to "the pontiff, the laws of the Holy See, the whole Catholic Church and Vatican City State."

Much of the material simply summarized information collected during the initial investigation of Gabriele and the testimony given during his trial Sept. 29-Oct. 6.

But the judges' reactions to several points raised by Cristiana Arru, Gabriele's lawyer, were explained in detail, particularly regarding Arru's contention that since the material found in Gabriele's apartment consisted of photocopies, not originals, the former butler didn't actually steal anything.

First, the judges said testimony from Msgr. Georg Ganswein, the pope's personal secretary, and from Vatican police officers who searched Gabriele's Vatican apartment proved to them that a few originals were among the photocopies.

Second, they said, Gabriele removed the originals without permission in order to photocopy them, but even more, they said, while he might not have stolen many original documents, by photocopying them he took the information written on them without consent.

"The paper document is nothing other than the support material for an immaterial content," the judges said.

During the trial, Arru repeatedly raised questions about the Vatican prosecutor's assertion that police found in Gabriele's Vatican apartment three items given to Pope Benedict as gifts: a check for 100,000 euros ($123,000); a gold nugget from the director of a mining company in Peru; and a 16th-century edition of a translation of the "Aeneid."

The judges' explanation of their verdict basically said they made their judgment based on the theft of confidential papal and Vatican documents, not on the three gifts.

A separate area of the report concerned whether or not Gabriele was capable of understanding his actions, which the judges answered affirmatively.

The judges cited several statements made by Gabriele, both during the investigation and at the trial, to the effect that he knew what he was doing was wrong, he took extra precautions to avoid being caught and he went to confession when it became clear he was about to be arrested.

The judges also discussed the points that, in their view, made Gabriele's actions a case of "aggravated theft" and not simple theft.

The main aggravating factor, they said, was the fact that Gabriele abused his position of trust: "In effect, Gabriele was able to commit the crime he's accused of because of his work relationship with the Holy Father, which necessarily was based on a bond of trust."

Gabriele's job brought him into the very private life of Pope Benedict, and the butler violated the "absolute reserve" such a position required, the judges said.

"He used this unique position to perpetrate his criminal actions," they said.

While recognizing that Gabriele was not paid for leaking the documents to an Italian journalist (who, in turn, published them in an instantly best-selling book), the judges said he still committed the crime with the intent to profit from it "intellectually and morally."

The judges quoted him as telling investigators, "Even if the possession of those documents was illicit, I felt I had to do it for various reasons, including my own personal interests." Gabriele, they said, felt having the documents would help him better understand the inner workings of the Vatican, and leaking them to a journalist would help him provide the "shock" that could lead to change in the Vatican, which he felt was becoming filled with corruption and careerism.

In the verdict, the judges ordered Gabriele to pay the Vatican's court costs, which Lombardi said amounted to the equivalent of about $1,300.