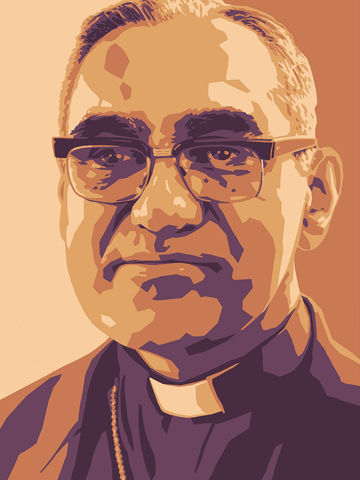

(Julie Lonneman)

The beatification of martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero on May 23 will acknowledge what has been celebrated throughout Latin America since his assassination at the altar on March 24, 1980, in El Salvador. Romero gave his life as a good shepherd for his flock in a time of persecution. He modeled what a bishop looks like in a church committed to justice for the poor. Romero's death and the baptism of blood endured by the people of El Salvador during its 12-year civil war (1980-92) inevitably have larger implications for the universal church, and for us in North America.

Pope Francis' determination to advance Romero's cause for sainthood recognizes this witness. It also reveals the influence Romero is having on Francis' own goal as pope -- to move the global church closer to the kind of church that emerged in El Salvador under Romero, whose story is a road map to such a church.

This article explores some of its characteristics: a church faithful to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, fully engaged in the modern world and its economic and social struggles; a pastoral church reaching out to the suffering and neglected people at the margins of society; a more vocal and prophetic church challenging global systems that oppress and exploit the poor; and an evangelizing church that practices what it preaches and lives what it prays.

A Vatican II church

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, chief advocate for Romero's cause, called him "a martyr of the church of the Second Vatican Council." Romero's choice to "live with the poor and defend them from oppression" flowed from the documents of Vatican II and of the 1968 meeting of Latin American bishops at Medellin, Colombia.

It was at Medellin that the phrase "God's option for the poor" first entered official church language, a major shift at a time when the Catholic hierarchy in Latin America was seen by many as aligned with the rich and powerful.

At the heart of the debate over the nature of the church that ensued during Vatican II was whether God's entry into human history in Jesus was only for eternal life beyond this world, or if salvation also included God's presence in the struggle for social justice, human development and freedom from poverty and oppression in this world.

The "Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World" gave the answer in its opening lines: "The joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially those who are poor or afflicted in any way, are the joy and hope, grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well" (Gaudium et Spes 1).

For Romero, the Incarnation meant that the life, death and resurrection of Jesus are a present reality, the engine of history, active in each generation of the church. As the Good Shepherd lays down his life for his flock, so Romero chose to die with his beloved people rather than flee to safety or compromise the Gospel to accommodate the forces attacking the church. After Medellin, theology had to grapple with history.

A church in history

As popular liberation movements flared up in the developing world in the post-colonial period of the 1960s, the United States saw communist infiltration everywhere and interjected its Cold War interests around the world. This set up the context in which complex geopolitical and economic forces collided in Latin America with tragic consequences. El Salvador came under this template in the 1970s. As the influence of Vatican II led to greater church advocacy for human rights for the poor, entrenched regimes became more repressive, appealing to the United States for support and accusing opponents, even Catholic priests and nuns, of spreading Marxist ideology.

Romero was chosen as archbishop of San Salvador in 1977, because he was regarded as a safe, conservative spiritual leader who would not challenge the status quo in the small Central American nation run by a few wealthy families backed by the military.

But within weeks of Romero's installation, one of his rural pastors and a close friend, Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande, was murdered by government soldiers for supporting the poor campesinos trying to organize for land reform and better wages. Romero emerged from the crisis as a devoted pastor and champion of the people. Six priests and scores of pastoral workers, catechists and faithful church members were killed in the months ahead. When asked by a reporter what he did as archbishop, Romero answered, "I pick up bodies."

He immersed himself in the plight of the victims and their families. He became the voice of the voiceless, using his Sunday homilies, broadcast by radio throughout the country and the region, to tell their stories and to demand that the government account for the hundreds of people arrested, tortured and disappeared as tensions worsened toward civil war.

Romero was accused by critics inside and outside the church of "meddling in politics" and subverting the spiritual mission of the church, which they said was to save souls. Far from abandoning church teaching, Romero was applying the documents of Vatican II and Medellin, and the papal encyclicals of Pope Paul VI to the reality of the people of God in El Salvador.

A church of the poor

Once Romero had decided to challenge El Salvador's wealthy minority backed by the army, his fate was joined to the poor majority. His term as archbishop (1977-1980) became a three-year martyrdom of vilification and constant death threats. Romero and the martyred church of El Salvador revealed the cost of church advocacy for the poor.

The historic complicity of the church with wealth and power was one of the scandals of the pre-Vatican II church. It continues to be a challenge, as evidenced in recent efforts to cleanse the Vatican bank of secret accounts and money laundering. The question is whether the church's silence can still be bought with philanthropy for charitable works from wealth created in unjust ways that exploit the poor and ignore the common good.

Pope Francis has insisted that real solidarity with the poor in their struggle to participate in shaping the future for the entire human family is essential to the church's mission of evangelization.

A pastoral church

Such a church will not happen without good leaders. Romero modeled Pope Francis' image of the pastor "who smells like the sheep," immersing himself in the lives of workers, students and families, especially children and the elderly. Wherever he went, they surrounded and embraced him. As personal attacks from the highest levels of power increased, even emanating from the Vatican, Romero found solace and strength in the people. He discovered in them what John Henry Newman had called the "third magisterium" -- the experience of the laity -- which forms the sensus fidelium on which church doctrine is ultimately grounded.

Pope Francis knows from his own experience in Argentina that this is where bishops encounter the church of the poor and receive their credentials as servant leaders.

A collegial church

Vatican II was synonymous with dialogue toward consensus. The council's four sessions helped the bishops recover their role as apostolic partners with the pope. The process of decision-making is as important as the outcome. Full, active participation by all in discerning and owning pastoral policy is what forms us as church.

Romero led by consensus, consulting his clergy and pastoral staff of religious and laity on his homilies and the four pastoral letters he wrote as archbishop, which addressed every aspect of the life of the church in crisis. He was a "martyr of meetings," something everyone understands, convening and attending endless meetings to listen exhaustively to every point of view before decisions were made.

Conscious of the scrutiny he was under, Romero recorded everything, even his personal reflections, into a tape recorder each day. He left a paper trail that protected him from revisionist critics who called him a Marxist, a dupe to Jesuit influence and a heretic. His meticulous records show how engaged he was with his local church.

Romero valued consultation over top-down, closed-door decision making because he saw how it led to better pastoral solutions. Pope Francis affirmed this same principle when he opened the 2014 Synod of Bishops on the family to broad input from the laity and encouraged debate among the participants. He has also affirmed regional conferences of bishops and subsidiarity at all levels.

A collegial church is messier and riskier than one that prizes continuity over adaptation and enforcement over discernment. Pope Francis wants a living church open to God's surprises. This is what enables us to resolve the apparent paradoxes of joining mercy to justice, love to truth, ideals to reality.

Authentic worship

Romero understood the power of public worship to reveal the deeper mysteries of God. Especially at Sunday Masses, he reminded the faithful of their baptismal identity and communion as members of Christ's body. His homilies made the Scriptures and the liturgical seasons come alive in the experience of the people, uniting their struggles and sufferings with those of Jesus. Even in the most violent times, he reassured them that they were never alone, because God was accompanying them in their pilgrimage through history.

Romero's final days mirrored Lent and the approach to Holy Week. His last homily, delivered the week before Palm Sunday, the day of his funeral, was on the Gospel from John 12:24-26: "Unless the grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies it remains alone. But if it dies it produces much fruit." Moments later, in full vestments, standing at the altar in a small hospital chapel, he was shot and killed by a sniper. The meaning of the Mass was graphically revealed, and the Word of God he had just preached "came true in our hearing" (Luke 4:21).

Romero's death summarized his priesthood and joined him to the priesthood of thousands of martyrs who had already died and were to die in the years that followed his murder.

Worship that is ritually correct but empty of the realities it symbolizes makes religion irrelevant. Only when liturgy does justice and connects the life of Jesus to our lives is it effective as Christian formation. Pope Francis seeks to re-evangelize the church today by making the same connections. He is scripting his papacy from the Lectionary readings he preaches on at his daily Masses. By word and example, the life the church is being proclaimed as the life, death and resurrection of Jesus unfolding within the liturgical year and within history.

Call to conversion

An uncomfortable but inescapable history lesson awaits North American Catholics who want to know about this newest saint and martyr. Romero's beatification will attract global attention to El Salvador and to the questions, "Who was Oscar Romero, who killed him, and why?"

Responsibility for crimes committed in El Salvador continues to elude full adjudication. Yet it is hard to deny that among the many factors that created political and economic instability in the region was the long history of U.S. involvement, including the overthrow of governments not in step with our national interests, and the support of corrupt, repressive governments that served our Cold War agendas.

Within this framework, the United States funded the war in El Salvador that killed over 75,000 people, most of them civilians. Salvadoran soldiers trained and advised by the U.S. military, using U.S. weapons, planes and helicopters, massacred thousands of defenseless people in El Mozote and the Sumpul River. Elite troops who murdered six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter on the campus of the University in San Salvador in 1989 had just returned from training at the U.S. School of the Americas.

The road to sainthood for Romero is a call for us to be aware of the role our country is playing in the world. Romero's message of peace and reconciliation, justice and mercy is meant for us. Even more, Romero now points the way forward in the direction that Pope Francis has said he wants to lead the entire church.

What role American Catholics and our elected government play going forward will depend on whether we experience a profound transformation of mind and heart. Can we question economic systems we benefit from that are built on the backs of the global poor? Our own survival is at stake in an increasingly unstable world. The cost of change is our conversion to greater solidarity with our brothers and sisters around the world. A different world is possible and necessary.

It will take a committed global church to alter the direction of history toward a more just, sustainable future. Romero and the people of El Salvador gave their lives for such a church, and Pope Francis seems determined to invite all of us to be part of it.

Blessed Oscar Romero and the Martyrs of El Salvador, pray for us.

[Pat Marrin is editor of Celebration, NCR's sister publication. This article first appeared in the July 2015 issue of Celebration.]