Bishop Raymond Hunthausen walks in St. Peter's Square after having attended the Sept. 27, 1965, working session of the Second Vatican Council. (AP/Gianni Foggia)

Raymond Hunthausen, then the doughty, little-known archbishop of Seattle, suddenly rose to national attention in the 1980s when he condemned nuclear weapons on the grounds of the Trident submarine base that stored scores of them.

The startling specter of a robust, genial prelate staring down the monstrous might of the U.S. submarine strike force, which he alarmingly called the "Auschwitz of Puget Sound," sparked huge debate, especially as he plied his steady vigil, backing up that protest by refusing to pay a portion of his federal income tax, thereby committing civil disobedience. Though he was branded a "communist" and a heretic by foes, his stance was that of a Christian pacifist, ringing with theological, biblical and humanitarian appeals.

Hunthausen's emergence as a new face and new voice in the broader rally against nuclear arms awakened many to that threat. His passion and courage won him a large following of admirers and defenders in the aftermath of the Vatican backlash that soon mounted against him. The punishment wore down his resistance, eventually driving him to resign.

In the span of his 96 years, which ended in August 2018, that brief slice of activism, marching with the core of resisters at the site of the most lethal submarine ever made — each of the 14 vessels capable of bearing 20 nuclear missiles — became the most dramatic and purposeful period of his life as it's portrayed in Frank Fromherz's A Disarming Spirit: The Life of Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen.

Franciscan Sr. Katarina Schuth talks to NCR about meeting younger people where they are.

The biography traces his momentous and unanticipated plunge into political dissent to an accumulation of tugs toward activism. As a young man, he was horrified by the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. Later, he was inspired by the peace advocacy of Thomas Merton and the tireless anti-war protests and repeated jailing of Jim Douglass. His broad ethical scope saw all other justice causes threatened by nuclear annihilation, the weapons themselves a strategy by which the rich and powerful retained power and privileges. The advent of the mammoth Trident installation in his archdiocese provided Hunthausen the occasion for coalescing those anti-war and pacifist instincts. He spoke eloquently and acted dauntlessly in support of those ends.

The rest of his long life story is only partially told, however, owing to a shortage of fresh reporting on the long-term aftermath of that confrontation and his blunt demotion by the Vatican. He spent his last 27 years in retirement, virtually sequestered in a Montana cabin, declining interviews concerning that ordeal.

A retrospective appraisal of that highly publicized traumatic period, during which he was widely viewed sympathetically as a victim of Vatican retaliation, is therefore missing. The central dramas of his years as a bishop are therefore incomplete.

Among those issues ripe for update were: the initial shock when an auxiliary bishop of Pittsburgh, Donald Wuerl, was suddenly imposed on him, ordered to take over five main areas of his authority despite his vehement objections; the stunning withdrawal of support from fellow American bishops when Rome retaliated; accusations that a style of lax leadership allowed violations of official church teachings and practices to gain traction in the archdiocese; continuing speculation that Vatican attacks on his integrity and dignity had driven him to early retirement and seclusion (at age 70) thereby achieving the pope's objective.

Hunthausen thus left the public stage as a pointman for a rising Catholic peace movement to dwell in the shadows as if he had been ostracized for disobedience. Fromherz argues persuasively that he did not feel that judgment, but solid evidence one way or the other from the archbishop does not appear further in these pages. His withdrawal from the field and basic silence, however, leave the story of that incandescent, extraordinary witness incomplete. Missing elements are sometimes unavoidable, and Fromherz apparently never challenges Hunthausen's prohibition on further exploring that ground.

The gaps stem significantly from the author's approach. From the outset, his adulation of Hunthausen is unstinting even as he vows to withhold his own opinions from the controversies. But the pledge collapses in a steady stream of tributes that effectively promote a heroic portrait of a besieged bishop mistreated by church officials and rules out consideration of his culpability and personal flaws. His brief for Hunthausen is passionate and deeply researched, but by effectively omitting the final third of his life, that profile is largely impervious to certain public challenges that did arise during that decadeslong blackout that Fromherz does report. The most telling are charges that he had overlooked serious sex abuse by some priests. He conceded in court that he had paid too little attention to them. Not discussed and still puzzling is why he stepped down from his highly visible leadership in the Catholic peace movement.

The biography therefore largely keeps the archbishop encased in superlatives drawn from highlights and heroism from three decades or more ago. Even at that, Hunthausen felt it necessary to control the narrative by getting Fromherz to withhold publication while he was still alive.

Advertisement

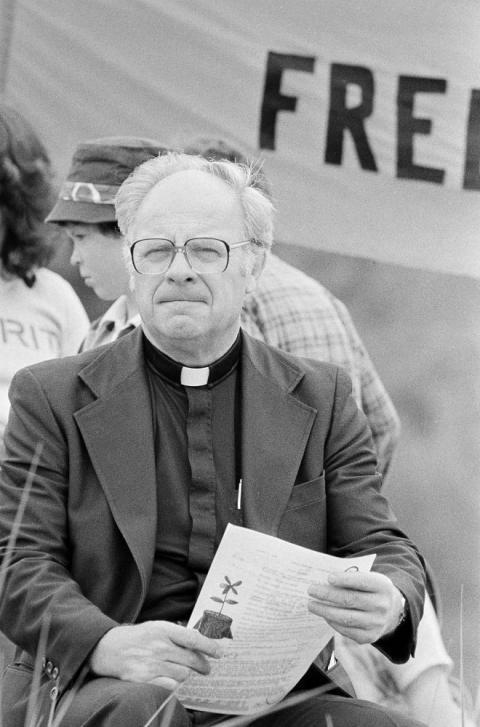

Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen sits among several thousand anti-nuclear protesters at a peace rally on the Kitsap Peninsula about 10 miles north of the Trident Navy Base at Bangor, Washington, Aug. 8, 1982. (AP/Barry Sweet)

Fromherz's handful of cited interviews with Hunthausen may have probed the archbishop's retrospective views of the controversy, but there is no evidence of that in the book. He does, however, meticulously trace Hunthausen's background, drawing on news articles from his hometown, Anaconda, talks with fellow seminarians, records and testimonies from his years as professor, coach and president of Carroll College, highlights of his first appointment as a bishop in the Diocese of Helena, Montana, finally the documents from his spirited, anguished clash with church authorities. The detail is rich and well-woven, though much is familiar.

Fairly or not, Fromherz generally acquits Hunthausen from a criticism on the basis that he functioned on motives generated by authorized Vatican II renewal. He is, accordingly, placed in the vanguard of the council's vision, a reliable interpreter of its implications. As such, his putting those values into practice risked charges by conservatives that he was out of step. But Fromherz believes his motives were honorable, not those of a maverick but as a beacon for a church aborning.

Arguably, Hunthausen had both a loner/maverick side that coincided with a conformist side. He rattled cages by relaxing top-down authority in favor of collaboration and by his anti-establishment protests and refusal to pay income tax, but he also adhered assiduously to hierarchical direction. He signaled approval of some bending of canon law, such as allowing some remarried Catholics to receive Communion without benefit of annulments but didn't openly campaign to alter church teachings. He welcomed women into diocesan leadership and policy-making councils, but stopped short of endorsing the ordination of women or full equality. He permitted gay and lesbian Catholics to meet in the cathedral, for which he suffered reprimand, but didn't lobby for full acceptance of homosexuality.

None of that complexity diminishes his exemplary standing as a spiritual and moral exemplar; it only expands his portrait beyond the tighter boundaries of character that are obtained in this biography. He took a stand on an issue he felt paramount and was true to it.

Fromherz promulgates a very human figure, both virtuoso and facilitator, a loveable man who displays the trailblazer resolve of his native Northwest and the egalitarian leanings of Vatican II's "people of God"; a man who believes in consensus rather than hierarchical rule, yet bears the impulse to go his own way when he deems it necessary; a man of complexity who comports himself with graciousness and deceptive simplicity.

On the national front, his collaborative impulses either failed or were stymied beyond his ability to be a rallying point for anti-nuclear brother bishops. He did his own thing — and well — but not in the service of bringing divided minds together in conciliar fashion. He bore witness without winning many colleagues to his reform-mindedness. His potential for that may have been damaged beyond repair if he felt fellow bishops had failed him in his time of greatest need. In any event, he showed little ability or desire to coordinate larger causes.

As Fromherz abundantly documents, Hunthausen braved the brickbats of crusaders against his anti-war activism and his variances from church orthodoxy. Within the church, he fought the sanctions imposed on him, and achieved a partial settlement, but never coalesced with other Catholics to urge doctrinal or clerical reform. He left the field in apparent defeat.

Fromherz's prodigious energy and insight memorializes an inspiring, noble man whose depth of alarm over nuclear annihilation gave him an honored, even revered, place in America's faith history. I'm grateful for that while also wishing I had learned more about who he really was.

[Ken Briggs reported on religion for Newsday and The New York Times, has contributed articles to many publications, written four books and is an instructor at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania.]