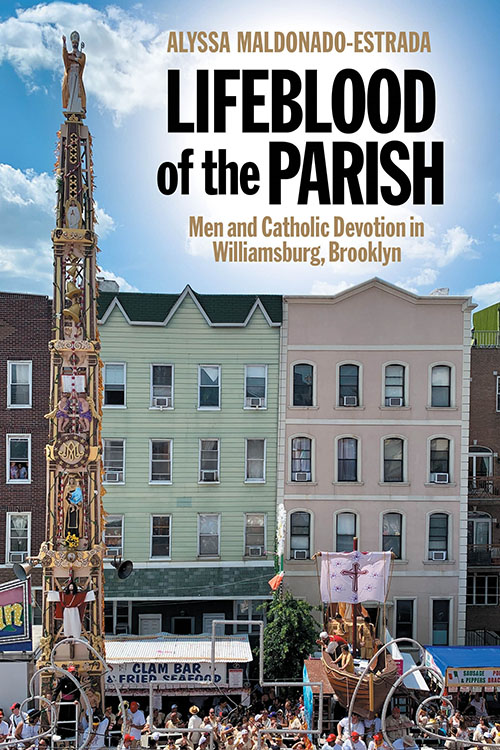

Men carry the 1-ton steel tower during the 2015 giglio parade in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York. (Dreamstime/Rebekah Burgess)

Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada paints a portrait of Williamsburg tradition and devotion that predates $30 brunches. Lifeblood of the Parish is a detailed ethnographic account of Italian American Catholicism and masculinity at the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, called OLMC. Maldonado-Estrada, focusing on the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and the Dance of the Giglio, gives readers a window into the world of male Catholic devotion in Brooklyn.

Through incredibly detailed imagery, accounts and reflections, we enter a community not just through a public-facing feast but also via planning committee meetings, church basements, money rooms, over-the-top costumes, tattoos and male kinships.

The feast and dance take place over 12 days in July, culminating on Our Lady of Mount Carmel's feast day on the 16th. It has been celebrated in Williamsburg since 1887 and 1903, respectively. The Dance of the Giglio can be traced back to Nola, Italy, almost a thousand years ago — many of the families of this parish are direct descendants of the Nolani immigrants who settled in Brooklyn in the 1880s.

On the first day of each year, planning for the almost two feasts begins. The men plan everything from processional routes to T-shirt colors. Every detail is meticulously mapped out over the course of seven months.

Maldonado-Estrada describes how much scholarship has been focused on women's devotion and "created a binary that codes devotionalism as an especially female domain of practice." Lifeblood of the Parish questions this binary and asks for a more extensive definition of devotion — which the rest of the book seeks to answer by showing its readers how the OLMC men "enact their Catholicism together" — a devotion not usually seen up on the altar during Mass.

We are given backstage access to an intimate tradition that fleshes out how "masculine Catholic bodies are not born but made." The author describes how these men's devotion to the parish is "about service ... time, training, and giving," generating a piety that is intergenerational and enduring.

This devotion shows itself in the form of molding and painting saint statues, woodworking, wearing costumes, directing the 65-foot-tall giglio ("lily" in Italian), carrying it on their backs and keeping count of the money raised during the feast. But the most important devotional job of all: to pass down these same practices to future generations of OLMC men.

Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada (Provided photo)

The book expertly weaves in Maldonado-Estrada's relationship to these men. Over years, she gains access and their trust, eventually becoming an "observant participant." She gains access to these traditionally homosocial spaces by putting in the work toward the feast.

When Maldonado-Estrada entered the church basement, which doubles as the giglio workshop, she couldn't maintain the idle ethnographic gaze — especially not after the men found out she had taken some art classes and could be put to painting panels of the tower. "That embodied engagement in the form of painting was a type of ethnographic apprenticeship and that without it spaces of masculine practice would have remained closed to" her.

She also kept specific accounts of the money generated from raffles, ride tickets, Mass collections and beer sales. She also worked the shrine, carrying boxes of candles out of storage, sold rosaries and prayer cards and "tossed dollar bills into plastic yellow boxes and watched as people lit candles and kneeled before the statue of Our Lady of Mount Carmel nestled in the back of the outdoor space."

Maldonado-Estrada also writes about the devotional tattoos these men decorate their bodies with. Even as they struggle with parish attendance in a neighborhood seemingly more concerned with craft cocktails than crafted Virgin Marys, "these men tattoo themselves into a narrative ... they write themselves into feast history as makers of the giglio." The history of the shrine and the feast is etched onto their skin, "a love of saints, tradition, parish, and other men — is written and worn on their bodies."

The tattoos are a medium for sharing stories, a way to record memories of what the feast has meant to them and their community over the years. With these tattoos they are able to display publicly the bonds they have to the saints and to each other.

In a particularly poignant anecdote, Joe Mascia, the social media manager of the church and a lifelong attendee of the feast (in his own words, since he was in his baby carriage), speaks about how his devotion is connected to his lifting work. "Throughout our interview, Joe told me at least seven times that he could not put into words his experience in Nola. He privileged body over meaning. What he did do was mime how he moved his body under the poles."

The memory of lifting the giglio was not something that just remains in photos or through his stories, but instead is imprinted onto him — creating an experience of the feast that is only archived through the male bodies. He extends the OLMC space and traditions to thousands, using social media. For Mascia, these skills allow him to serve the parish and the saints.

For these men, who have grown up in the church across multiple generations, it becomes their life's mission to keep the parish afloat, particularly through soliciting money and increasing Mass attendance. Maldonado-Estrada writes that money is "intertwined with intergenerational bonds between men, loyalties to the church, and ideas about survival and community longevity."

Advertisement

OLMC encourages this work because the bottom line is about life and death for this parish. Soliciting money, the author points out, is religious work.

The book also highlights the "urban exodus" or white flight that has occurred over the last few decades, especially among descendants of Polish, Irish, German and Italian immigrants. Throughout the book, we learn that even many of the men who organize the feast don't live in Brooklyn anymore.

"The success of the feast is in part contingent on Haitian devotees who visit from other parts of Brooklyn," writes Maldonado-Estrada.

Despite this, many Italian Americans "construct Haitian devotion as different from their own: admirably emotional but also excessive, superstitious, and foreign, revealing the logics of gender and productivity that undergird their definitions of devotion." The Italian American Catholics create boundaries with Haitian Catholics "by mobilizing discourses that once set them and their devotional practices outside the bounds of 'good' American Catholicism."

This becomes a point of contention between both communities when speaking about who is "doing devotion correctly." As these men see their life's work reflected onto the feast and the construction of the giglio, therefore the parish, the racist propriety judgments are based on an alleged fear of the "other" encroaching on their territory, sentiments many of OLMC's parishioners have heard echoed nationally from President Donald Trump.

Lifeblood of the Parish — the name former OLMC pastor Msgr. Joseph Calise gave the feast — offers readers a look into a complicated history between various cultures and communities, one collectively built up over decades and, quite literally, on the shoulders of men. Maldonado-Estrada complicates what masculinity looks like in the Catholic Church, marking it as a process that occurs over years of piety, devotion, but above all work.