Mercifully, author Daniel Hornsby gives us no road-trip romance about being "out there" or any lofty passages on the grandeur of the American West. (Unsplash/Diego Jimenez)

I've occasionally been grateful not to have been a fisherman in Galilee 2,000-plus years ago. I worry I would have been asked to follow and wouldn't have been able to. I'm afraid I would've just kept on fishing.

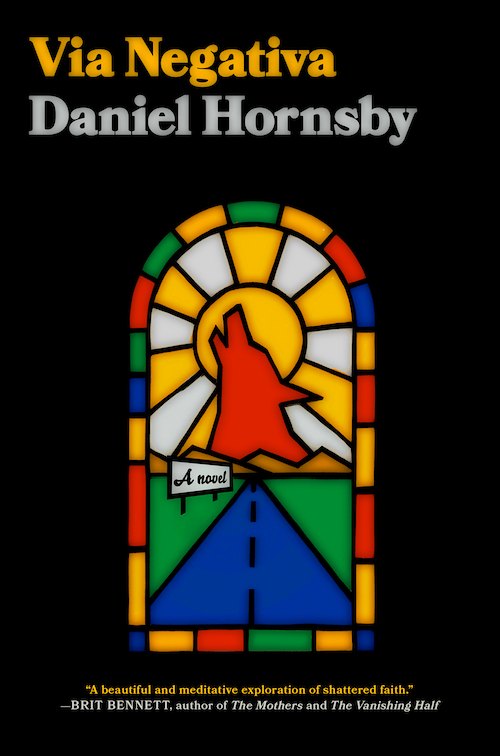

In Via Negativa, Daniel Hornsby's funny debut novel about guilt, we meet our protagonist, Father Dan, as he's driving west through Kansas. He finds an injured coyote, who we come to know as Bede, on the side of the road. He nurses Bede back to health and keeps him sedated with painkillers for much of the journey west. It's an act of goodwill, but more importantly, it's a way for Father Dan to prove to himself what a good Franciscan he still is. He's 70 and newly homeless, expelled from his Indiana diocese and on his way to meet some old friends.

The circumstances of his expulsion are eventually explained but aren't very important, since it's as much a figurative excommunication as it is a literal one. Father Dan is an anachronism, and a little bit of a liar. An aloof, artsy, left-leaning oddball, he could so easily have been a caricature, but his voice is what draws you in and wins you over. It's the heart and the motor of the book.

Oversized crosses and billboards of "singer-songwriter Jesus in his white karate robes" follow Father Dan like specters as he drives west through Kansas, headed toward Seattle. We spend most of the drive in his head, looking back on his life; from his childhood spent in a junior seminary up through his tenure in the priesthood with regrets wrapped in jokes.

Vignettes that feel like little parables play out as Dan makes stops along the way. They include a dog named Reese Witherspoon, a teenage pyromaniac, and a waiter with an unforgettable story about a supernatural encounter with Carrie Underwood. Mercifully, Hornsby gives us no road-trip romance about being out there or any lofty passages on the grandeur of the American West. I did roughly the same drive as Father Dan quite a few times while shuttling back and forth between college in California and my parents' house in Kansas City — it's a slog of a drive and one I have very little nostalgia for. Like real road trips, Via Negativa does drag a bit in the middle. But overall, Hornsby keeps us alongside him with plain, understated prose and a conversational tone.

There's a sure debt to Charles Portis' road novels here; Portis' dry humor and the spirit of his eccentric and endearing idiot-protagonists feel very much alive in Father Dan. There's also the occasional passage that feels ripped right out of a Cormac McCarthy Western, such as Father Dan's thoughts on highways.

A road is a stripe of death, it requires a streamlined apocalypse to be born: hacking down forests, leveling the ground, blasting through layers of rock. Then, once the road is there it becomes a trail marked by white crosses and piles of deer … patches of mashed, illegible gore. All killed by machines that run on the black rot of microscopic creatures, the dead that power death. A road is a long absence, a black line crossing things out.

The title takes its name from the ancient practice of Christian mystics who defined God only by what it is not, or "by way of denial." Or as he puts it in the end of the first chapter,

I hate the billboards. I hate that giant white cross in Effingham. I don't like holy cards all that much. Even crucifixes bother me sometimes. If anything, all my vision-seeking has only confirmed the paradox of God hiding, perfectly, in plain sight. If we want to see God in the world, all we have to do is see the world. If we want to see God in human form, look at people. Look around. Turn around. Billboards should be outlawed, not just the Jesus ones. They block the sky and my view of the trees.

This concept is the linchpin that holds together the rest of the complex spiritual framework Father Dan has built for himself over the course of a lifetime as a hermit in the middle of a community. Obscure movements from the early centuries of Christianity, geodesic domes and the music of Prince all play roles in this tapestry as well. It's an engrossing place.

Advertisement

As the curtain gets drawn back and we begin to get a clearer, messier portrait of Father Dan, the line between enlightened theology and elaborate coping mechanism blurs. Watching Dan move through the world as it is, outside the safety of the rectory, what we see isn't a current day Thomas Merton committed to study and contemplation, which is how he sees himself, but rather a lonely and damaged old man who has spent a life in hiding, confronting the fact that he may have played a role in covering up clerical sex abuse. His behavior is erratic, and he's all over the place emotionally and physically, grappling with the weight of that, and with the very real possibility of taking revenge.

Has he seen glimpses of the divine, or was that just wishful thinking? This is a question Hornsby comes back to throughout the journey, particularly in the memorable final scene.

Father Dan is dumb in a way that only a smart person can be. He's singular and totally familiar. NCR readers will appreciate his little asides on minor saints, obscure Christian communities and some deep-cut theological history.

Hornsby doesn't make any firm judgments, and gives us ample time and space to arrive at our own conclusions. Is he someone who tried to do the right thing, in his own dense way, or is he a man that just kept on fishing?