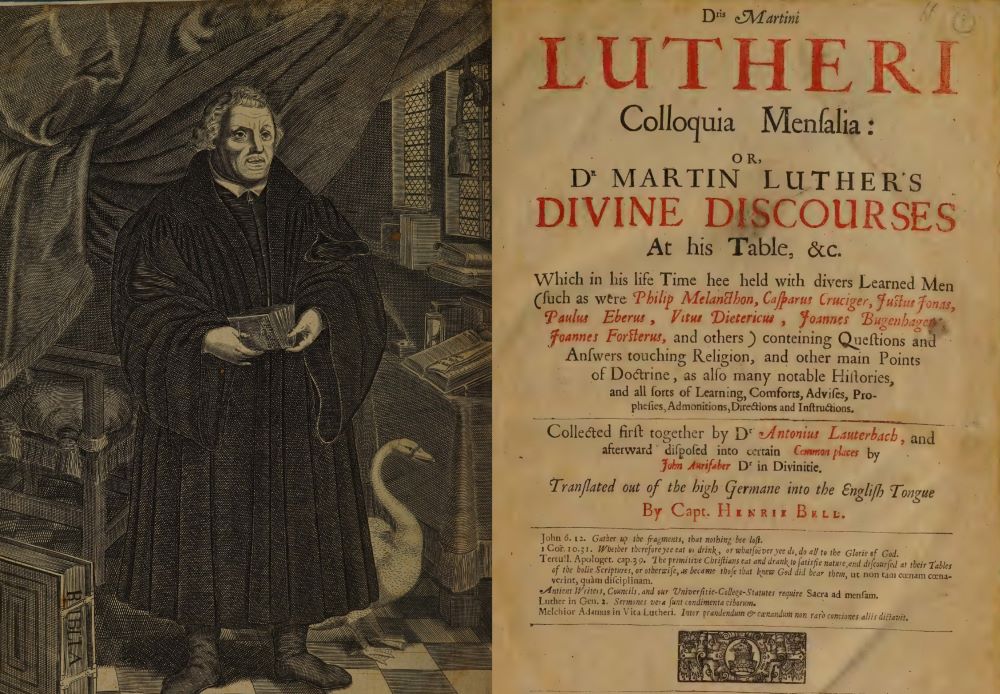

Martin Luther used the medium of print to distribute and popularize his ideas after 1517. Pictured here is a portion of the frontispiece of the first English translation of his "Table Talk," edited by Captain Henry Bell and published in London in 1652. (Wikimedia Commons/Internet Archive)

When Martin Luther chose the medium of print to distribute and popularize his ideas after 1517, the Lutheran message spread like wildfire through Europe. It has been estimated that the total print run of pamphlets in the first years of the Protestant Reformation went into the millions of copies. The Reformation can therefore be regarded as the first large-scale media campaign in the West.

What is less well known is that the Roman Catholic Church too made smart use of print both before and after the Reformation. It adopted the new technology early after its invention in the 1450s. In Papal Bull: Print, Politics, and Propaganda in Renaissance Rome, Margaret Meserve, professor of history at Notre Dame University, writes that the papacy had a "greater command of print and its possibilities than previously realized." The church first used printing for "operational" purposes such as the printing of indulgences, which helped to produce income. Papal decrees or bulls, traditionally written on parchment and authenticated by a lead seal (bulla) that was appended to them, were now also issued in print. Still, however, the manuscript bulls had to be publicly affixed in certain places, such as church doors in Rome, in order for them to be valid.

In contrast to its quick adoption of the press for "operational" reasons, the papacy was relatively slow to adopt print for political purposes. Only Pope Sixtus IV, in the late 1470s, began to use print for his propaganda wars.

Beginning in the late 1470s, the papacy used print to foster the cult of saints and to encourage pilgrimages to Rome. Above is a print (circa 1540-66) by French artist Nicolas Beatrizet that depicts Veronica with the veil said to have touched Jesus' face during the Passion. (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953)

An example described by Meserve is the battle of pamphlets between Rome and Florence after the 1478 Pazzi conspiracy, in which a member of Florence's ruling family, Giuliano de' Medici, was assassinated during Easter Mass in the cathedral. Pope Sixtus had been in contact with some of the conspirators, and there was a backlash against some members of the Tuscan clergy who were directly involved in the conspiracy. Archbishop Francesco Salviati was hanged from the windows of the Palazzo della Signoria. In a heated exchange of accusation and counteraccusation that Meserve dubs a "war of words," both the pope and the Medici drew attention to their respective positions through printed pamphlets.

Meserve also shows that the papacy used print to foster the cult of saints and to encourage pilgrimages to the Eternal City. A striking example of this is the Veronica, the veil said to have touched Jesus' face during the Passion. Devotion to the Veronica is attested to in Rome from the 12th century, and it had been used specifically to attract pilgrims to the city on the occasion of jubilees since 1300.

In the 15th century, numerous pamphlets with woodcuts popularized the Veronica more widely throughout Europe. Meserve gives a rich and fascinating array of examples of these early depictions of the relic. In a similar fashion, the legend of the Holy House of Mary in Loreto, which was believed to have been flown by angels across the Mediterranean, was the object of large-scale attention in early printed pamphlets. Under the "warrior pope" Julius II (1503-1513), papal print production became decidedly political again. Julius used print to garner public support for his wars and to assert his authority.

Despite the papacy's adoption of the revolutionary technology of print, the printed message that it transported remained conservative. As Meserve argues, "constraints of papal ecclesiology restricted the pope's use of new technology to broadcasting a remarkably retrograde vision of his office and the Church." This in itself is probably not very surprising. What is striking is the variety of different uses to which print was put in the service of the papacy. In printed works, theological points such as papal primacy and salvation by good works were defended, heretics and enemies of the papacy were condemned, and support was raised for future Crusades against the Turks.

Meserve concludes pithily that "the medium could not, by itself, modernize the institution." Her narrative ends just before Luther burst onto the European scene, and she implies that it was only the Council of Trent (1545-1563) that reformed, in addition to the medium, also the message conveyed by the Catholic Church.

Advertisement

Another aspect of this story that might have been worth discussing is the papacy's engagement with print privileges and press censorship. Since the late 15th century, the popes issued a number of regulations that sought to control the book market, prohibiting unwelcome publications and granting the imprimatur for those that were deemed fit to print. This process of control and suppression could perhaps be seen as the flipside of the coin of papal print production.

Meserve's Papal Bull is an expert guide to the world of printing in Renaissance Rome, and it offers many relevant suggestions for further reading. Her book, based on impeccable research, is as careful and thorough as anything that has been written on Rome in the pre-Reformation period.