Detail of "Wolf and Fox Hunt" painting by Peter Paul Rubens, circa 1616 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1910)

Francis has recently proclaimed this "The Year of Saint Joseph." Now is as good a time as ever to look at art from the perspective of labor. We can turn to Marxist theory to help inform our visual imagination — rooting it in the charism of the working class. John Molyneux's new book The Dialectics of Art offers a solid Marxist framework for the discerning viewer.

Molyneux is a British socialist, activist and writer, writing from outside of the academy without a specific art historical specialization. This brings with it certain self identified limitations — namely the credibility that comes along with expertise — but frees him to create a compelling, wide-reaching story of art in the age of capitalism, roughly from the Italian Renaissance to today.

He structures his book "like a sandwich." First he asks the age-old question: "What is art?" before considering how we judge art. The meat of his sandwich is a collection of long and short reviews from his career as a critic in socialist publications: looking at the likes of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rembrandt van Rijn, Pablo Picasso, the Young British Artists (especially Tracey Emin) and Yasser Alwan at length, while briefly considering the work of Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon and Peter Paul Rubens. He concludes with two chapters on "How Art Develops" and "The Dialectics of Modernism."

For Molyneux, art is "is a kind of spiritual health food which contributes to the development of the human personality, especially among working-class people" when they can freely access it. Art arises out of a definite historical and social context, creating a human response to that specific moment in the history of class struggle. What makes something art is the nature of the labor of its production. Molyneux's central thesis is that "art is work produced by unalienated labor." His understanding of art is process oriented: "it is the unalienated, self-directed labor of the artist or artists that determines the character of the work as art."

He outlines a number of things to look at when judging art: mimesis, skill, beauty, the sublime, ethics, emotional power and expression, social and psychological realism, innovation and, finally, critique of the context from which it comes. Only in the final analysis should the work be assessed by political criteria — for Marxists "politics is about the survival and liberation of humanity."

Advertisement

In his application of this methodology, Molyneux brings us on a journey of art through the ages. A welcome journey for those of us who have not been able to travel for the past many months, let alone visit a museum. From the Italian peninsula, through the Netherlands, Spain, the British Isles, America and Egypt, we watch capitalism, art and labor morph themselves across time and space.

Where Molyneux fails is with his reliance on a hegemonic canon of Western art. He does little to challenge the canon's lack of diversity in the roster of artists he puts forward. Of the nine individuals he discusses, eight are men and eight are of white European descent — leaving the two chapters not focusing on white men to feel tokenized. The exploration of Emin's work was interesting, but following a review of the 1997 Young British Artist Sensation exhibit she appeared in felt repetitive. He would have been better off editing the two reviews into one, making room for another chapter. Another chapter could have easily explored the work of Jacob Lawerence or the Mexican muralists he quickly mentions in passing.

His lone chapter not to focus primarily on an artist of white European descent is also his only chapter not to feature a household name. He introduces Alwan as a Nigerian born, Iraqi descended, American raised photographer working in Cairo, Egypt. Alwan's way as a photographer is to "show that working people, despite poverty and toil, remain complex and dignified human beings, damaged but not utterly defeated, with their own take on life and the world."

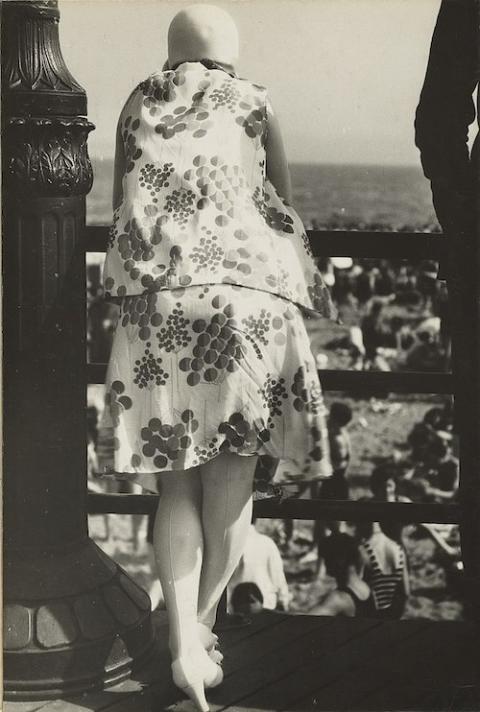

He places this in the historical context of the medium, evolving out of the sympathetic photography of Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and August Sander, in conscious opposition to the exploitative objectification of Diane Arbus, Joel-Peter Witkin, Robert Mapplethorpe and Martin Parr. Molyneux presents Alwan's specific artistic interest in working class people as a "rarity." Reading with the hindsight of the Arab spring, we are lead to make the leap to understanding Alwan's practice as revolutionary.

"Coney Island Boardwalk, 1929," gelatin silver print by Walker Evans (Wikimedia Commons/Getty Open Content Program, http://www.getty.edu/about/opencontentfaq.html)

Molyneux's apparent lack of expertise in photography undermines the point he is making. A reader with even a passing interest in fine art photography can easily think of a number of photographers that work in a similar way as Alwan. Some of the first images that jump to the forefront of my mind are Carrie Mae Weems' womanist "Kitchen Table Series" from 1990 looking at Black domestic life; Jess T. Dugan's intimate portraits of transgender and gender nonconforming people aging in the 2018 portfolio "To Survive on this Shore;" or Janet Delaney's photographs of working class people in her "South of Market 1978-1986" series.

Unsurprisingly, when we look beyond a canon of white men, we can easily find images that present working class and oppressed people with dignity. Women, LGBTQ and BIPOC photographers have been making these images since the dawn of photography. Presenting Yasser Alwan as a rarity or revolutionary tokenizes him, marginalizing the tradition he emerges out of.

Molyneux's inability to fruitfully present a challenge to the canon of Western art — especially when it comes to race — is the central failure of The Dialectics of Art. Don't throw the baby out with the bath water, however. The methodology he presents for looking at art from a Marxist perspective is still sound. His central thesis holds tight and can be used — by viewers, critics and art historians without his particular blindspots — to widen our understanding of art "as a potential model for freedom."

In his apostolic letter proclaiming this the year of St. Joseph, Pope Francis writes: "The crisis of our time, which is economic, social, cultural and spiritual, can serve as a summons for all of us to rediscover the value, the importance and necessity of work for bringing about a new 'normal' from which no one is excluded." This is a call to action for us as consumers of art and culture to expand our canon and to create a more inclusive new normal. In The Dialectics of Art, John Molyneux gives us some tools to do just that.