A mural of hip-hop artists J Dilla and MF Doom (Wikimedia Commons/Athenz Iluz)

Toward the end of American record producer and rapper J Dilla's life, when he wasn't producing or receiving ongoing treatments for his combination of lupus and the blood disorder TTP, he was particularly interested in interpreting God's word. During Bible study led by his mother, Maureen Yancey, Dilla, born James Dewitt Yancey, grew fond of the Book of Job, relating to Job's strength in the face of adversity. In the biography Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm, author, educator and journalist Dan Charnas decodes Job 38:4 in plain meaning, a semblance with Dilla's transient life: "Where were you when I created everything? You cannot even begin to comprehend where you fit in my plan."

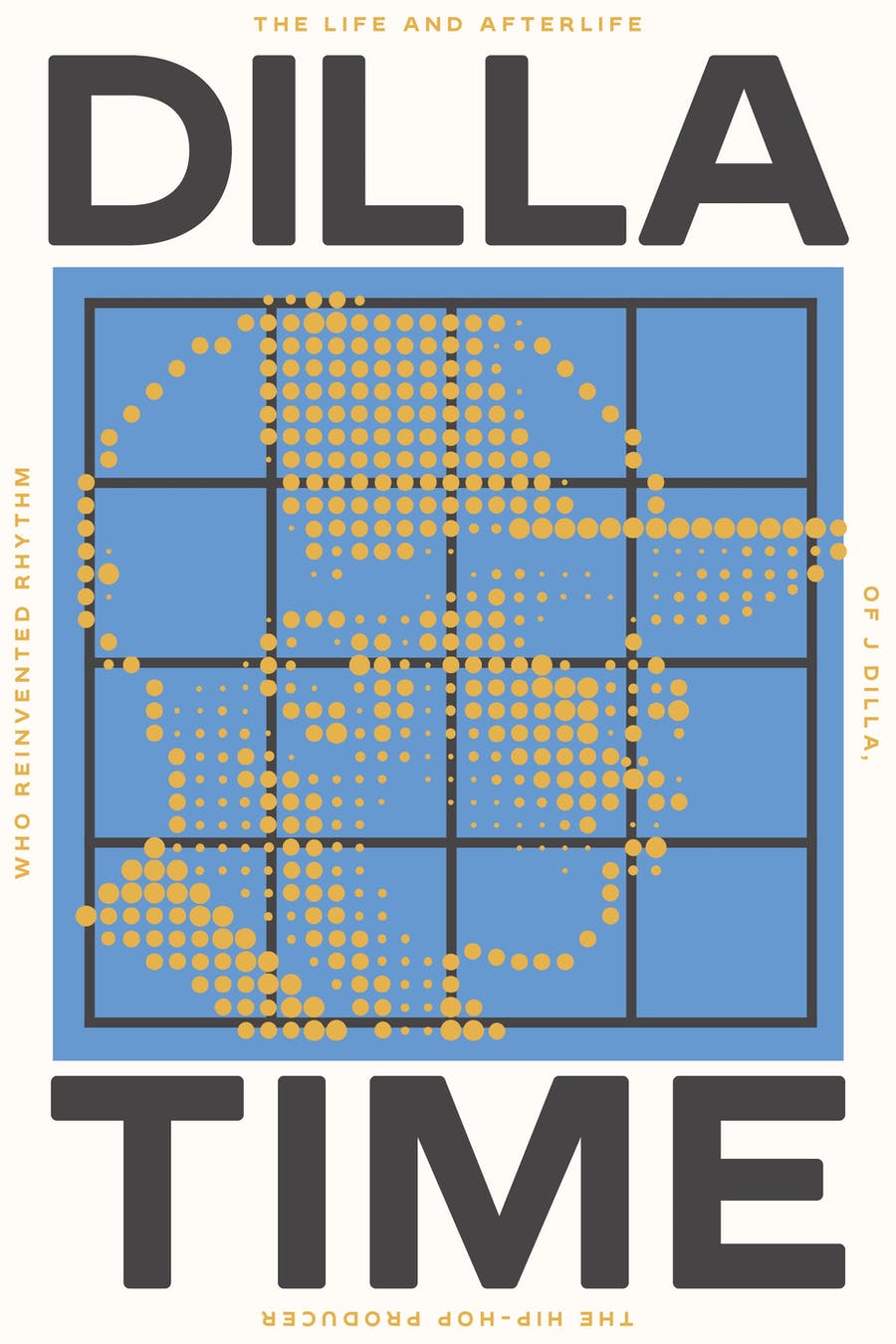

In Dilla Time, the progressive beatmaker's plan has been immortalized. Largely based on Dilla repaving traditional music by creating a third path of rhythm, Charnas had the immeasurable concept of Dilla Time in mind. Teaching New York University's Clive Davis Institute course "Topics in Recorded Music: J Dilla," The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop author partnered with fellow educator and musicologist Jeff Peretz to set a visual language to illustrate Dilla's rhythmic concepts. In tune with the book's time feel, segments also pace between Dilla's interpersonal relationships and career. Dilla Time was released Feb. 1 — just six days shy of Dilla's 48th birthday — and in 16 chapters, Charnas demystifies how the producer, who died in 2006 at 32, redefined Detroit's sound, crafting an intergenerational influence on hip-hop.

Dilla Time opens with a lesson on syncopation, a disruption in rhythm that didn't adhere to the tonal system of traditional European music during the colonial enterprise. Defying the precise European standard and going one step further with polyrhythm, Afro-diasporic regions placed musical events where listeners wouldn't expect to hear them. Charnas gives readers a lesson on 20th century syncopation in Black American music, from disjointed ragtime to the southern emergence of blues. With framework illustrations to guide readers through polyrhythmic and "swung" movements, Charnas lands on the manifestation of Black Detroit culture, where Conant Gardens was the city's first Black middle class district during World War II. Also the foundation of Dilla's familial roots, the Motor City became the cornerstone of Motown Records, the apex of Black music through doo-wop and soul during the 1960s.

Advertisement

It was in Detroit's Harmonie Park where a 2-year-old Dilla would play turntables with his father, Dewitt Yancy. The nascent prodigy was born from Maureen and Dewitt who aligned through their shared love of music — Maureen studying classical voice in high school and Dewitt being a songwriter and music producer. In 1976, it had been just four years since Motown Records departed for Los Angeles, but the Black music canon had grown, with 1970s funk transforming into a new genre: hip-hop. By the 1980s, hip-hop culture had swelled and Dilla's turntables were turned in for a digital sampler and beat machine, both integral to him becoming a pantheon of the genre.

While briefly attending John J. Pershing High School in the early 1990s, Dilla met his future members of rap group Slum Village as they originally formed as Ssenepod — dopeness spelled backwards. Considered a "mad scientist" for his organic technique of deconstructing samples into a prenatural form, Dilla received training from local soul musician Amp Fiddler, who also gave Dilla his first in-studio experience. Fiddler believed in the young virtuoso who intentionally created "error" in his production, a subtle nuance that Charnas notes "turned the beatmaker into an alchemist." After heading to Lollapalooza in 1994, Fiddler introduced Dilla to Q-Tip, the frontman of pioneering alt-rap group A Tribe Called Quest, and Dilla got his first taste of veneration after Q-Tip heard his beat tape.

The two became partners in production as Q-Tip threw Dilla — then known as Jay Dee — into the music business vortex. Although Dilla introduced Q-Tip to Slum Village, the rapper-producer was only interested in Dilla as a singular force, advising established hip-hop acts like The Pharcyde to work with him. In 1995, The Pharcyde released their sophomore album "Labcabincalifornia," where Dilla received credits for producing six tracks, including "Runnin," the samba-driven track that became the group's signature.

It was with Q-Tip and fellow A Tribe Called Quest member Ali Shaheed Muhammad that Dilla became a part of production collective The Ummah, with occasional appearances from D'Angelo and Raphael Saddiq. Although the Arabic "ummah" translates to "brotherhood" or "community," Dilla felt isolated, growing disillusioned with not being fairly credited for his "simple-complex" technique that made him perceive many relationships, even business ones, as merely transactional.

While regarding Dilla as a genre-shifting exemplar, Dilla Time also captures the producer's flaws, including anger issues, infidelity and violence against women. Once when his attorney Micheline Levine was in Paris attending her sister's funeral, Dilla called her in a temper and cursed her out. His mother, Maureen, stepped in to calm him.

In fact, Maureen, affectionately called "Ma Dukes," nearly takes over her son's narrative through legal disputes following his untimely death, replicating Dilla's short temperament to ensure that the industry didn't exploit his legacy. An encapsulating and wide-ranging 480-page epic, Dilla Time is mainly ingrained in the development of the artist's sound and music eras, but the latter half of the book awkwardly tries to fit Dilla's illness, family and legal drama with the producer's monolithic purpose. Still, Dilla Time examines and humanizes how man became the machine, breaking Detroit's grid and changing the way the generations of hip-hop enthusiasts consider the genre.