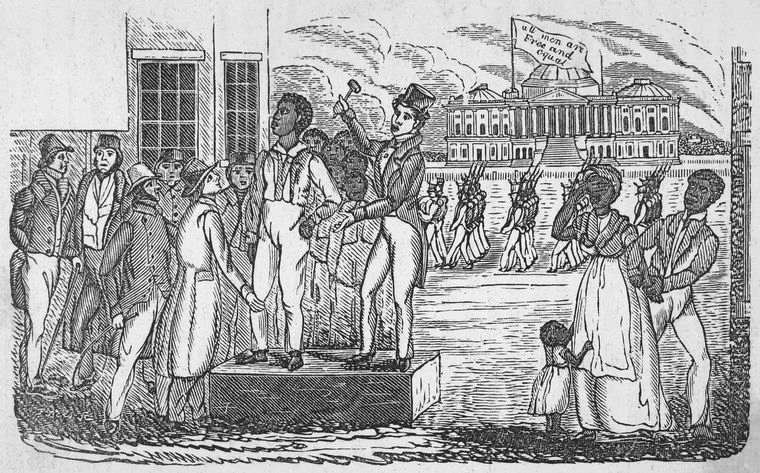

A slave auction is illustrated in the 1862 book Slavery in South Carolina and the Ex-Slaves by A.M. French. (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Part 2 of 2. Read Part 1 here: Historian confronts complexities of early America's self-evident truths

On Wednesday, I began my review of the splendid book Self-Evident Truths: Contesting Equal Rights from the Revolution to the Civil War by Richard Brown. I had timed this review to coincide with consideration of Brett Kavanaugh's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, because the sloppy invocation of "the intent of the founders" is too often mouthed by dullards who know little about the founders and their intentions. In any event, the confirmation issue has shifted to different issues, with one exception that I will mention in due course, and the issue of natural equality is one that must be faced by each generation anyway.

Wednesday, we discussed how natural equality emerged in the lexicon of the generation of American patriots who led the Revolution, and looked specifically at how the aspirational promises of the Declaration of Independence applied to religious freedom. Today, we look at Brown's treatment of the interplay between ideas about equality with people of color, women and children and, finally, property and aristocracy.

If the principle of religious equality had largely taken root by the time of the Civil War, with all the states disestablishing the religion of their founders and extending the franchise to Catholics and Jews, the promise of equality contained in the Declaration of Independence had been thoroughly betrayed as it pertained to black and Native Americans. Brown's account makes for grim and necessary reading.

The founding generation was beset by ambivalence. Patrick Henry, the firebrand who had early on set the terms of the imperial conflict in the starkest terms — "Give me liberty, or give me death!" — recognized as early as 1772 that slavery was "a species of violence and tyranny ... .destructive to liberty." He believed that "every thinking, honest man rejects it [slavery] in speculation, how few [do so] in practice." Brown argues that Henry was distressed by his own moral culpability but unable to overcome his situation, a slave owner in a slave-owning economy, sitting in the House of Burgesses with other slave owners. "I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living here without them. I will not, I cannot justify it."

The problem was not only slavery, although that was obviously a problem. Racism affected the treatment of free blacks as well as slaves and did so in both South and North. Indeed, the treatment of, and understanding of, both slaves and free blacks was a constant source of contention in the period between the Revolution and the Civil War.

Massachusetts had never been home to a significant slave population. As a colony, the legislature voted to ban the additional importation of slaves in 1771, but the governor vetoed it. Yet, one of the most consequential founding fathers, John Adams, "exploited common negrophobic prejudices in his 'Humphrey Ploughjogger' essays against British imperialism," Brown writes.

In addition to common prejudice, Adams and others Massachusetts rebels celebrated the right to property. During the revolutionary ferment on either side of the start of war in 1775, "a consensus was emerging that slavery was contrary to Christianity and natural rights. But these nascent abolition beliefs were offset by a profound commitment to property rights coupled with widespread antagonism toward blacks — people whose different appearance, customs and behavior, and poverty made them more likely than whites to become tax liabilities requiring public assistance." You might say the founders were opposed to royalty but were already trafficking in the myth of the welfare queen.

William Byrd was a prominent Virginian and slave owner who, two generations before the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, wrote, "All nations of men have the same natural dignity, and we all know that very bright talents may lodged under a very dark skin. The principal difference* between one people and another proceeds only from the different opportunities of improvement." After the Revolution and before the century closed, this argument from natural equality became widespread.

The "Plan for Liberating the Negroes within the United States" was published by Ferdinando Fairfax, heir of one of the Commonwealth's great families, in 1790. He called for voluntary manumission and African colonization. He suggested Congress finance a slave "buyout" if manumission did not entirely free the slave population. But his scheme would founder if it violated property rights: "To deprive a man, at once, of all his right in the property of his negroes, would be the height of injustice, and such as, in this country, would never be submitted to," Fairfax said.

The slave burial ground and Slave Memorial at Mount Vernon, Virginia, the home of George Washington (Wikimedia Commons/Tim Evanson)

I had long recognized that to credit any moral superiority to George Washington over his decision to free his slaves upon his death, over against Thomas Jefferson's failure to do so, overlooked a key historical fact: In 1794, Eli Whitney received a patent for his cotton gin. At the end of the 18th century, with the decline of the tobacco industry, slaves were becoming more of a burden than an asset. As the use of the cotton gin became widespread, the value of slaves needed to harvest cotton restored their value. Washington did not realize how valuable his slaves were when he wrote his will. Jefferson did when he wrote his.

Brown explains that this change in the economic value of slaves was not the only dynamic in play. "By the first decade of the nineteenth century, even before the cotton boom revitalized slavery and slave prices, the doctrine of natural equality was losing its appeal," he writes. "When African American citizenship moved from a theoretical future to become present reality, many whites embraced a different natural law, one that reinforced old prejudices. They came to justify unequal policies by invoking inherent natural characteristics ranging from physiognomy and skin color to mental aptitudes — a science of race. As with the ideal of natural equality, Thomas Jefferson stood in the vanguard." Thus was born on American soil the first full-fledged ideology of white superiority.

The North Carolina Constitution of 1776 afforded free people of color some measure of equality, including the franchise, which was remarkable for its time. It was not until 1835 that the constitution of the Tar Heel state was amended to bar "any free negro, free mulatto, or free person of mixed blood," from voting. In two states along the Mason-Dixon Line, Maryland and Pennsylvania, a practical concern seemed to prevail: In areas where there were sufficient numbers of free blacks that they might tip an election, they were barred from voting, but in areas where they were few, they were granted the franchise.

The final triumph of the science of race — which, I might note, would have been considered at the time as "being on the right side of history" — over the ideological commitment to natural equality came with the infamous Supreme Court decision in Scott v. Sandford in 1857. Chief Justice Roger Taney, arguably the most prominent Catholic in the country, wrote for the court, "The legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither ... slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument."

Brown deftly catalogs the shift in thinking that gave rise to white supremacist views in the first half of the 19th century. Especially interesting is his examination of court proceedings. In one case, "Susanna" was a black woman in Schenectady, New York, charged with murdering "her infant male bastard child." Her own attorney, Theodore Sedgwick Jr., employed racial stereotypes to earn her acquittal, essentially making the case that the morals of blacks were so lax, no consequential shame was attached to having a child out of wedlock, and so the prosecution lacked a credible motive in the case. It worked: She was acquitted.

Brown also examines the trials of Prudence Crandall, a white woman who opened a school for both white and black girls in Canterbury, Connecticut, in 1831. She eventually won in the courts, and the arguments by the attorneys on both sides fascinate, but vigilantes shut her school down. I am fortunate enough to drive by the Prudence Crandall school whenever I go to the pharmacy.

I shall not examine Brown's treatment of the unequal status accorded to women and children, nor how class realities persisted even when the young nation was celebrating the equality of opportunity it afforded its people. For this, and it is all fascinating, you must purchase the book. I think the issue of how reformers changed laws pertaining to debt was especially important and really could have been penned in 2008 during the economic meltdown: Then, as two centuries prior, it was the rich debtor who benefited from reforms, not the poor one.

But, in light of the accusations against Kavanaugh, it is important to consider the degree to which women were considered second-class citizens, when they were considered citizens at all, in the 19th century. Strangely, and uncharacteristically, for a decade, from 1797 until 1807, women enjoyed the franchise throughout the state of New Jersey, a fact completely unknown to me before reading this book. But that was an outlier and it was quickly forgotten.

Advertisement

Brown examines the wide reach of the law of coverture, which made all of a woman's rights and property subject to her husband's will. Indeed, it is almost foolish to speak of women's rights after you read the lengths to which some women had to go to escape from vicious and violent husbands.

In most states, as in England, a divorce required an act of the legislature, and they were rarely granted. Brown notes that in Virginia, between 1786 and 1851, an average of 2.4 divorces were granted annually and there were plenty of petitions that demonstrated outrageous, even life-threatening, treatment of wives by their husbands.

What is inescapably clear is that during this period, with very few exceptions, women "from all classes accepted the conventional wisdom of natural difference and that subordination to men was proper."

Just as race has persisted to haunt the American imagination, and a strong commitment to private property has enshrined economic inequality, the assumptions that guide male behavior toward and thoughts about women are appallingly resistant to change. I do not know if Kavanaugh did what he has been accused of, but only a fool would think it is impossible, and that such a thing would have impeded Kavanaugh's rise to influence in his chosen profession and social universe. Jurist Zephaniah Swift published a treatise in 1795 that stated:

The common opinion of mankind declares, that it is a very different and much more heinous crime for a woman that is married, to have criminal conversation with a single man, than for a married man with a single woman. ... A married woman that submits to the embraces of any man but her husband, does by that act, alienate her affections, deprave her sentiments, and expose him to the greatest of all misfortune, an uncertainty with respect to his offspring. ... A married man may be concerned in an intrigue with a girl, without impairing his conjugal affection ... nor does that act produce such total depravity of moral character in a man, as in a woman; for when a female once breaks over the bounds of decency and virtue, and become abandoned, she is capable of going all lengths in iniquity.

The Declaration of Independence also spoke of the "opinions of mankind," and the belief that women were naturally inferior to men, and properly subjugated to them, was one of those opinions. It clashed then and clashes still, albeit in a severely diminished form, with the aspirational words about natural equality that followed it.

We Americans are still wrestling with the founding, but if reading Brown's splendid, careful, well-documented text proves anything, it is that the GOP senators who breathlessly invoke the need for an originalist on the Supreme Court are more than a little clueless about the historical origins of the texts they so venerate.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.

* This column has been edited to correct a quote.