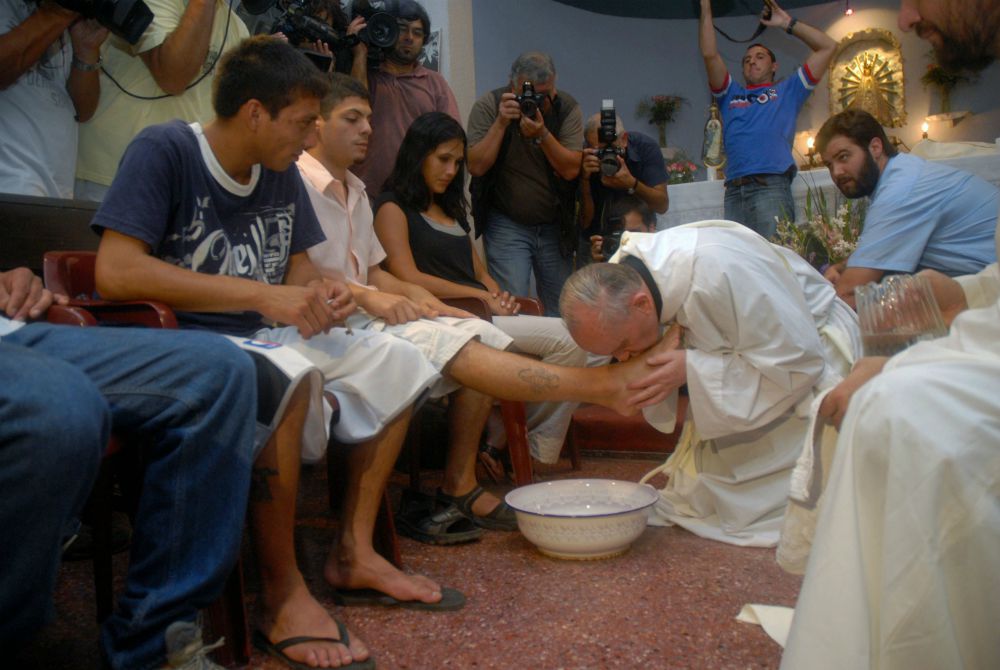

At Holy Thursday Mass in 2008, then-Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio washes and kisses the feet of residents of a shelter for drug users at a church in a poor neighborhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina. The cardinal took the name Francis after being elected pope March 13, 2013. (CNS/Reuters/Enrique Garcia Medina)

I started reading Rafael Luciani's new book, Pope Francis and the Theology of the People, months ago. I had to keep putting the book down and reading something else, not because the book was poorly written or because I found the subject matter uninteresting. Quite the contrary. No, I had to keep setting the book aside because reading it made me realize what a lousy Christian I am.

The theology of the people is not well known here in the United States. A couple years back, I attended a luncheon for Fr. Carlos Maria Galli, one of the leading practitioners of the theology of the people, and the poor, patient man had to cope with the most rudimentary of questions, and not just from the journalists. From the theologians too! Luciani demonstrates how and why the theology of the people had a formative impact on Jorge Maria Bergoglio, and also shows its continuing influence on his writings now that he is Pope Francis. This theology is critical to understanding not just the current pope but the church in Latin America which, increasingly, is not only leading the way at the Holy See but in the U.S. church as well.

This theology emerged in Argentina during and immediately after the Second Vatican Council, which sat from 1962 through 1965. The Argentine bishops, in 1966, issued a pastoral declaration for the post-conciliar period that recognized the paradigm shift Vatican II represented and pointed the Argentine church in a new direction:

Our great task at this time, in order to bring about the post-conciliar stage, must consist of three things: 1) Being imbued by the council, assimilating it by reflecting and internalizing its ideas and its spirit; 2) Consolidating and improving the communal form of the Church and its collegial structures: assembly of bishops, presbyterate, pastoral council, structuring and coordination of the laity; 3) Fostering greater openness to the world on the part of clergy and laity. This entails greater sincerity in fostering the spirit of poverty and service. In order to carry out this program, the Church in Argentina must increase reflection and dialogue in all sectors and on all levels.

So, right out of the box, you see the themes that would ripen in the church in Latin America: poverty, service, collegiality, dialogue, communal form of the church, openness to the world. But, there, unlike so many dioceses in the U.S., the bishops were in the vanguard, not fighting a rearguard action against the implementation of the council.

Advertisement

What was most distinctive about the theology of the people, however, was its understanding of the people as the locus for theological reflection and ecclesial credibility. The Latin American bishops' reading of critical texts of Vatican II, such as Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes, eliminated the possibility of any kind of privatized, pietistic faith, but it did more than that. It demanded that the church adopt the standpoint of the people of God and look at itself and at the world with all its hopes and fears, standing with and amongst the people. Luciani quotes theologian Rafael Tello:

The Argentine church must see itself and its problems from the standpoint of the people. The people would then be the illuminating and unifying element of the problematic of the Church. That means seeing it not in terms of its internal conflicts, its internal difficulties, or its internal issues but in terms of its insertion, as people of God, in the Argentine people. This would lead to a course of action connected to that insertion, namely, the retrieval of the Christian values that are in the people … seeing from the viewpoint of the people and adopting a people-centered approach to pastoral action.

It requires little in the way of imagination to link this reflection on the Argentine bishops' statements in 1966 with the pastoral approach of Pope Francis today. This is why Francis, the first pope not to have been present at the council, nonetheless seems to breathe the conciliar spirit as much as his predecessors, maybe even a little more.

Cover art for 'Pope Francis and the Theology of the People'

It is also not too difficult to see how this theology differs from, even as it takes up some of the same themes and confronts largely the same social reality, as the theology of liberation. Theologian Victor Fernandez is quoted:

It used to be said that the theology of the people opts for the ignorant masses, people lacking in culture and critical thinking. What the theology of the people advocates is something very different. It means regarding the poor not merely as the object of liberation or education, but as individuals capable of thinking in their own categories, capable of living the faith legitimately in their own manner, capable of forging paths based on their popular culture.

I think we are past the point in time when we need to be defensive about liberation theology's shortcomings. It tried to import analysis that could scarcely have been more alien to the people: It made them an "object of liberation." Apart from the fact that too many liberation theologians — not all — overlooked the reality of the lives lived under the precepts they were trying to baptize, the ugly reality that Marxism always turned out to be, liberation theology, for all its good intentions, carried with it a kind of intellectual noblesse oblige to which the Argentine theology was allergic.

Similarly, throughout the book, Luciani makes clear how different the theology of the people is from the kind of reflexive charitable concern that characterizes the church in the U.S. It is not that charity is bad. It is that it is insufficient. "A genuine personal and emotional conversion to the world of the poor — who constitute the majority of humankind — becomes absolutely necessary if we are to grasp the meaning of Christianity today and to respond to this time in which we are called to live," Luciani writes.

This identification with the poor is drenched in traditional Catholic belief. Fr. Lucio Gera writes:

In conversion, things — the world — are reinterpreted, they are re-felt — felt in a new way — they are re-done, somewhat like being recreated in their paschal newness; another starting point is used to reconstruct the meaning of the world. … The world in all its expanse is re-lived, not as a mere remembrance, which would be going back to live the old, but as resurrection, which is not to be understood only as living again, but as living anew, not as a new life, but living differently.

This cannot be confused in any way with a mere secular commitment to social justice.

We also can discern Pope Francis' repeated objections to ideological colonization. As Luciani explains, the point here is not for us informed Catholics to go and evangelize the poor in their barrios, bring to them our values and our visions. "The option for the poor begins from and unfolds in the life-world of the poor themselves," he writes. "It involves respecting their way of being in order to recognize them honestly and with feeling as true subjects of a historical process of development and liberation. When we stop seeing them as objects of study and begin treating the poor personally, that is when we begin to be evangelized by them. … It is in this shared everyday life where the beauty of a humanity that has been touched by the divine mystery is revealed to us." One of the few missteps, or oversteps, Luciani makes is where I have placed the ellipsis in that quote. He writes, "That is the path of conversion, not mediated by the liturgy but by everyday dealing with persons and their life stories." I reject this dichotomy: If you have seen a poor person walk into a beautiful cathedral, or singing a hymn lustily, you know that we need not choose between liturgy and everyday dealings. It is a rare foot put wrong in this otherwise remarkable book.

Luciani traces the development of this theology through the great continent-wide meetings of the Latin American bishops who, at Medellín in 1968*, Puebla in 1979, Santo Domingo in 1992, and, of course, Aparecida in 2007 where then-Cardinal Bergoglio played such a key role in drafting the final document.

I will pick up that history on Wednesday when I conclude this review.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

* An earlier version of this story provided an incorrect year for the meeting.

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.