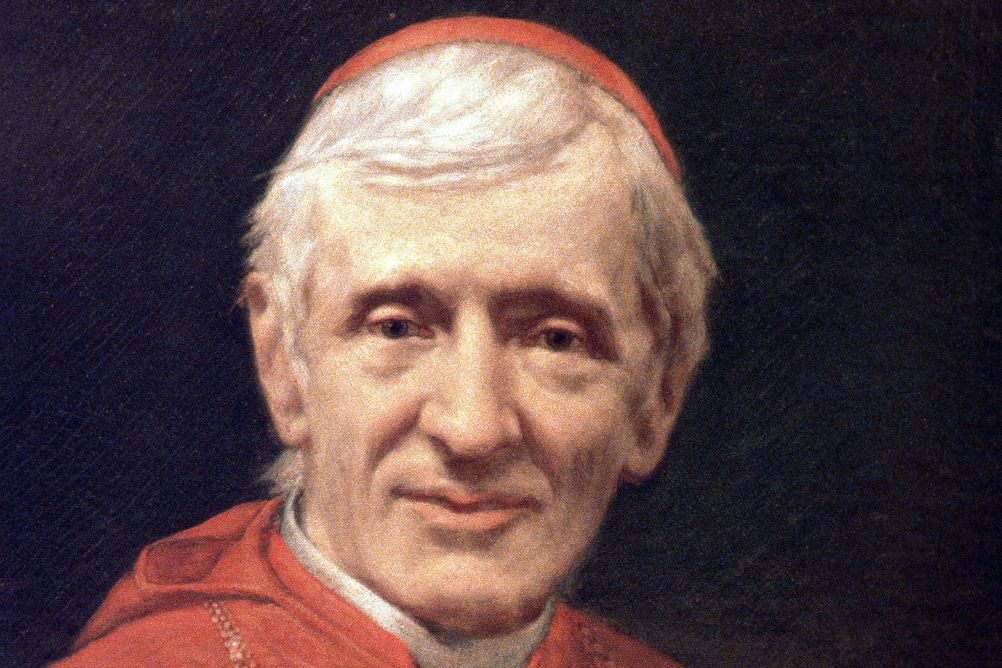

Detail of a portrait of St. John Henry Newman on view at a church in Rome (CNS/Crosiers)

Yesterday, John Henry Newman was raised to the dignity of the altar, as his contemporaries would have described his canonization. The event was almost as unlikely as his being raised to the sacred purple, as his being named cardinal in 1879 was described at the time.

I recall these ancient formularies because to the men and women of our time, Newman seems somewhat antique, his prose deliciously pre-modern, the span of his intellectual and spiritual development marked by a kind of rigor and depth not often found in this the Age of Twitter. For example, can anyone imagine themselves today writing this arresting description of the birth of his religious doubt in 1839 as he studied the Monophysite controversy:

My stronghold was Antiquity: now here, in the middle of the fifth century, I found, as it seemed to me, Christendom of the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries reflected. I saw my face in that mirror, and I was a Monophysite. The Church of the Via Media was in the position of the Oriental communion, Rome was, where she is now; and the Protestants were the Eutychians.

I speak of Newman's canonization being something of a surprise because we think of saints as patient and gentle people, but Newman could be churlish. Everyone has read his Apologia Pro Vita Sua, but I wonder how many skip over the correspondence between himself and Charles Kingsley that provoked it. Newman is searing, brutal even, taking no prisoners. And hilarious. It was reading that correspondence and the battle of pamphlets that followed, that made me see in Newman a kindred spirit: He was, both as a Protestant and as a Catholic, a controversialist of the highest order.

Advertisement

There the similarity between myself and Newman ends, for his mind and, even more, his learning exceed my own by the kind of measure usually reserved to calculations of galaxies. He had genius, too, which is a different gift altogether from intelligence and learning. An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine was not the work of a man who is merely intelligent, but of a genius, which is why that text, more than any other, is seen as the precursor of the Second Vatican Council. Who can speak responsibly or honestly about the right of conscience today without confronting the arguments contained in A Letter Addressed to His Grace The Duke of Norfolk on Occasion of Mr. Gladstone's Recent Expostulation? Is there a preacher alive today who comes close to achieving the erudition, both intellectual and emotional, found in Newman's Meditations and Devotions, Parochial and Plain Sermons?

How large is Newman in the landscape of Catholicism? I recall my great mentor, Msgr. John Tracy Ellis, speaking of Newman with a remarkable degree of veneration. "After the Lord Jesus and his mother, no single person has had a greater effect on my thinking and on my faith," he told our class one day, "than John Henry Newman." What the monsignor said of himself could be said of the universal church: The return to the sources in mid-20th-century theology could have happened in any one of a dozen different ways, but one of the principal ways that it did occur was through Newman's pen. We are, all of us, toiling in his shadow.

His being named a cardinal was certainly a shock. After his celebrated conversion, Newman found himself in an English Catholic Church that was increasingly at odds with his own ideas. Henry Edward Manning became a Catholic six years after Newman and a cardinal four years before him. Manning's ultramontane views, and dismissive attitude to the laity, to say nothing of their different temperaments and training, made a long lasting friendship or ecclesial comradeship unlikely. Newman's cautious and careful mind, given to second thoughts, made Manning suspect he was still an Anglican at heart. And it was Manning who became Archbishop of Westminster in 1865. Newman's career seemed consigned to the Oratory in Birmingham — until Leo XIII intervened and named him cardinal deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro. Fittingly, the church is not one of the baroque wonders that are so common in Rome but a seventh-century edifice in a simple basilican plan. The 13th-century portico and bell tower are decidedly medieval.

San Giorgio in Velabro church, Rome, 2005 (Wikimedia Commons/ William Domenichini)

Fr. Ian Ker, whose biography of Newman is the best there is, and whom I was pleased to meet and celebrate Holy Mass with some years back when he visited Washington, captures some of Newman's on-going relevance when he told NCR's Jonathan Luxmoore:

Newman was a complex and subtle thinker, who refused to see issues in black and white, and was both radical and conservative in his attitudes. He would have backed the reformers at Vatican II but would also have anticipated how they would later divide into moderate and extreme factions. Although he certainly believed in objective truth, he also saw how people saw proofs differently, in a way which remains relevant to current debates on atheism, scientific reductionism and post-modernism.

If the church in our own time is looking for a way to get past its ideological divisions, we could all start by reading Newman honestly, not looking to cherry-pick the parts that cohere with our own views, but allowing the parts that do not cohere to challenge us, as he allowed himself to be challenged. Newman defies, indeed his entire career is a rebuke to, the facile left-versus-right categories with which we are stuck. Certainly one group that has no right to claim his mantle as their own is the Cardinal Newman Society, the rightwing witch hunt group that monitors Catholic schools for whiffs of heterodoxy. He would be embarrassed by them to be sure.

Newman never came to the United States, but here are words of his from an 1839 article in the British Critic that Newman himself described as "flippant." His subject was the "American Church," for he was still a member of the Church of England in 1839 and recognized the U.S. Episcopal church as a daughter. His comments about U.S. society and religion are still astute:

Not to the poor, the forlorn, the dejected, the afflicted, can the Unitarian doctrine be alluring, but to those who are rich and have need of nothing… . Those who have nothing of this world to rely upon need a firm hold of the next, they need a deep religion … .

Such is the benefit of poverty; as to wealth, its providential corrective is the relative duties which it involves, as in the case of a landlord; but these do not fall on the trader. He has rank without tangible responsibilities; he has made himself what he is, and becomes self-dependent. … If he thinks of religion at all, he will not like from being a great man to become a little one; he bargains for some or other compensation to his self-importance, some little power of judging or managing, some small permission to have his own way. Commerce is free as air; it knows no distinctions; mutual intercourse is its medium of operation. Exclusiveness, separations, rules of life, observance of days, nice scruples of conscience are odious to it. …

A religion which neither irritates their reason nor interferes with their comfort, will be all in all in such a society. Severity whether of creed or precept, high mysteries, corrective practices, subjection of whatever kind, whether to a doctrine or to a priest, will be offensive to them. They need nothing to fill the heart, to feed upon, or to live in; they despise enthusiasm, they abhor fanaticism, they prosecute bigotry. They want only so much religion as will satisfy their natural perception of the propriety of being religious. Reason teaches them that utter disregard of their Maker is unbecoming, and they determine to be religious, not from love and fear, but from good sense.

God save us all — and by "all" I mean all, because this crimped sense of faith is found on both left and right, from "a religion which neither irritates [our] reason nor interferes with [our] comfort."

I shall finish with links to two of the hymns that the great man wrote. We sang "Lead Kindly Light" as the recessional at the Mass for my 34th birthday. "Praise to the Holiest in the Height" (sung to the tune "Billing," not "Gerontius") is slated to be the recessional at my funeral. Both hymns, in different ways, capture the thickness of Catholic faith, a thickness that no English-speaking man or woman has done more than Newman to elucidate. It is a beautiful, wonderful thing that the universal church now recognizes him as a saint. St. John Henry Newman, pray for us.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]