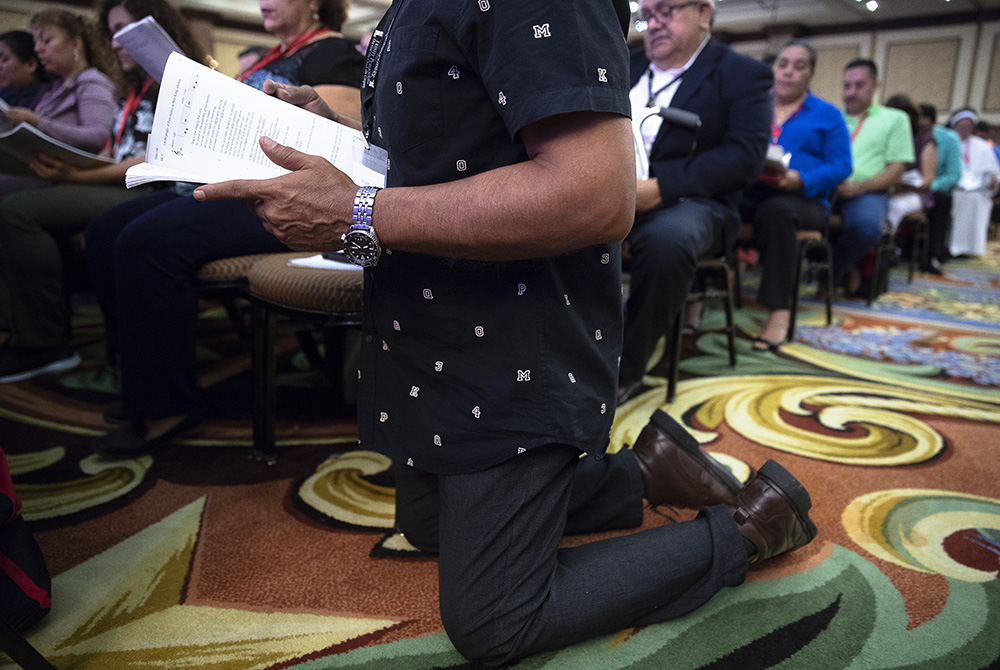

A delegate prays Sept. 23, 2018, during the Fifth National Encuentro in Grapevine, Texas. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

At this year's meeting of the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States, or ACHTUS, Jesuit Fr. Allan Deck of Loyola Marymount University spoke about the decline in church affiliation found throughout the United States, a concern for all of us who love the church. But he was not despondent, and he recognized in the history of Latino Catholicism some of the spiritual perspectives and resources that might guide the rest of the church in the U.S. as, together, we set about reconstructing our ecclesial reality in a post-pandemic world.

"We must remember that the identification of the majority of Latin American Catholics traditionally with the church is within the framework of popular religion rather than the highly standardized Tridentine Euro-American version of Catholicism," Deck said, calling attention to the ways popular Catholicism is about "living the faith domestically more than in the formal institutional structure of parish or diocese."

Deck noted the foundational and formative role of women in the Latino Catholic experience, saying "We also know that this popular Catholicism informally led by women — our mamás and abuelitas — stands in sharp contrast to the middle-class, doctrinal and moralistic Catholicism of the United States."

The professor went on to quote from the first Latin American pope, and his apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium: "Each portion of the people of God, by translating the gift of God into its own life and in accordance with its own genius, bears witness to the faith it has received and enriches it with new and eloquent expressions. … This is an ongoing and developing process, of which the Holy Spirit is the principal agent."

The ACHTUS meeting was no Pollyannish attempt to avoid reality. The presenters, including Deck, acknowledged the suffering that the pandemic had inflicted and the systematic sinfulness it had exposed. But what was missing — blessedly missing — from his talk and from most of the other presentations was the defensiveness that so often characterizes the statements of some of our bishops. These Hispanic theologians, both those who teach in universities and those who work in ministry, were never in a defensive crouch. They were not engaged in a stale apologetics. There were few straw men or women.

There was, instead, a kind of confidence, not only in the cultural history that Latinos bring to the task of evangelizing an increasingly secular America. Nor was the confidence rooted in any particular skills the theologians themselves displayed. No, theirs is the confidence of those who believe the Holy Spirit has not abandoned the church. And never will.

Those of us who grew up in the dominant Anglophone Catholic church in the U.S. inherit a legacy of defensiveness. In the 1930s and the 1940s, pastors led their flocks in signing membership cards in the Legion of Decency, pledging to condemn and avoid "all indecent and immoral motion pictures, and those which glorify crime and criminals." Closer to our own time, crusades against ill-defined enemies like "secularism" have become cornerstones of ecclesial analysis. Just this month, Phoenix Bishop Thomas Olmsted said his support for denying holy Communion to pro-choice politicians did not constitute politicizing the Eucharist but "protecting" it. Since when does the Eucharist need protecting?

Advertisement

The president of ACHTUS, Boston College professor Hosffman Ospino, encouraged his colleagues to embrace a "new ecclesial consciousness," and we welcome proposals from theologians who wish to engage the episcopal leadership of the church. A clear starting point for that conversation is the much neglected document issued by the bishops' conference in 1995 entitled "The Hispanic Presence in the New Evangelization in the United States." There we read:

In our country, the modern technological, functional mentality creates a world of replaceable individuals incapable of authentic solidarity. In its place, society is grouped by artificial arrangements created by powerful interests. The common ground is an increasingly dull, sterile, consumer conformism — visible especially among so many of our young people — created by artificial needs promoted by the media to support powerful economic interests. Pope John Paul II has called this a "culture of death." In the Holy Father's words, "this culture is actively fostered by powerful cultural, economic and political currents which encourage an idea of society excessively concerned with efficiency. … A life which would require greater acceptance, love and care is considered useless, or held to be an intolerable burden, and is therefore rejected in one way or another."

There is no defensiveness there, only a trenchant stance of cultural criticism informed by the Gospel.

The pandemic has put enormous strains on the various institutions of the Catholic Church in this country, but it did not stomp out the Gospel. We still celebrate Pentecost. Perhaps all of us in the Anglophone church need to listen more to the faith-filled confidence of our Latino brothers and sisters. In the face of the "modern technological, functional mentality," their communities and their theologians remind us not to despair. "The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes," Jesus tells Nicodemus. "So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit" (John 3:8).