Eva Fleischner is pictured in a screenshot from the "In Search of the Grail: The Story of a Women's Movement," a 2006 film for the U.S. Grail lay organization. (NCR photo/YouTube)

When Eva Fleischner left Boston for France in 1949 as a Fulbright scholar, she was engaged to be married. When her fiancé arrived in Paris to join her, she had changed her mind. Something deeper was beckoning: "If I had to pick one word for what had happened to me, it would be 'God.' "

What was it about that year in Paris pursuing studies in medieval philosophy that enabled her to discover, as she told her friend Herbert Heavenrich, author of In Search of the Sacred, "things I had been searching for all my life without knowing it"? How, then, in midlife did Judaism become so significant in her thirst for the living God?

Fleischner died in Claremont, California, July 6, 2020, the eve of her 95th birthday. I knew her as a woman of simple elegance and sophisticated thought, charismatic in an understated way.

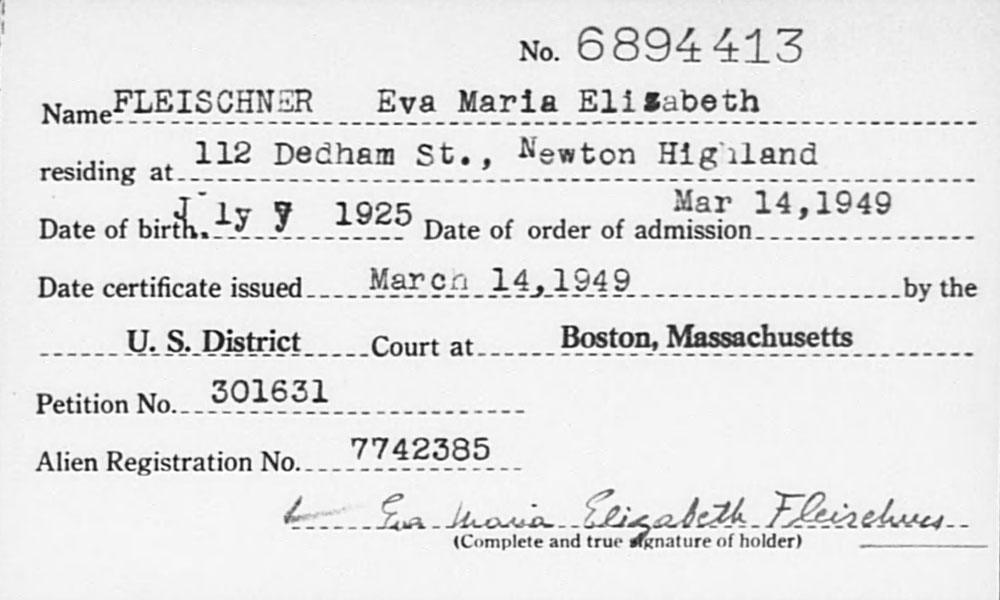

Fleischner’s peripatetic life began at 13, when her parents managed to get her out of Austria following the Nazi Anschluss (annexation) in March 1938 to a convent boarding school in England. She rejoined her parents in the U.S. in 1943, and enrolled at Radcliffe College. Graduating in 1946, she worked as an editorial assistant at Houghton Mifflin, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1949.

Eva Fleischner's U.S. record of naturalization is pictured. Fleischner escaped the Nazi Anschluss of Austria and rejoiced her parents in the U.S. in 1943; she graduated from Radcliffe College in 1946, and became a U.S. citizen in 1949. (National Archives Catalog)

Her Paris sojourn affected Fleischner profoundly, particularly her experience of the postwar renewal in the French church. Jesuit theologian (and later cardinal) Jean Daniélou at the Institute Catholique invited her to participate in Circle S. Jean Baptiste, a student group that studied other religious traditions and provided an expansive understanding of Catholicism.

About a year after her return from France, Fleischner took up an invitation to join an international women's movement, the Grail. Founded in the Netherlands in 1921 by Jesuit priest and scholar Fr. Jacques van Ginneken as a way to animate and advance women’s contribution to the church and world, the movement came to the U.S. in 1940.

Janet Kalven recounted in a 1993 article in the U.S. Catholic Historian that the two Dutch women who introduced this movement in the U.S., Lydwine van Kersbergen and Joan Overboss, conveyed the sensibility that "women count: together we can influence the course of history.”

By the time Fleischner traveled to Grailville, the U.S. center in Loveland, Ohio, in 1952 to spend a year of intense formation, it was becoming a prominent center of church renewal foreshadowing the Second Vatican Council, especially in liturgy and in scripture-based study and prayer.

In 1957, Fleischner pledged to live a life of devotion to God through the mission of Grail. She told Heavenrich, "It was through the Grail that I found purpose and meaning in life … and with a whole new commitment which I didn’t know was possible before."

Life in the Grail fostered what became Fleischner’s deep connection with the Psalms. In an autobiographical essay in Faith Transformed: Christian Encounters with Jews and Judaism, she wrote that the Psalms "profoundly and permanently changed my prayer life and my relationship to God." They also "predisposed me to eventually appreciate Judaism."

The years at Grailville allowed her to obtain a master's degree in liturgical studies at the University of Notre Dame — and to gain a stellar reputation as the head of their bakery, overseeing the production of 50 loaves of bread a day.

Unsurprisingly, the opportunities the Grail offered women at times led to conflict with ecclesiastical authorities. Fleischner experienced the shadow side of Catholicism in a dramatic way in 1963.

Advertisement

The Grail had sent her to Rome for the second session of Vatican II as a reporter for its publication Ecumenical Notes. An accredited journalist, Fleischner was included in an invitation to the otherwise all-male U.S. press corps to attend Mass on Oct. 30, 1963, in St. Peter’s Basilica. As the approximately 20-member U.S. press corps made its way to Communion, a Swiss Guard physically restrained Fleischner, preventing her from receiving Communion and leaving her in "tears of rage."

This unforgettable experience presaged a much longer encounter with Christianity's sinfulness. In the late 1960s she began doctoral studies at Marquette University in historical theology. Reading Martin Luther for a seminar, she was shocked by his vilification of Judaism. Her study of Christian texts across the generations revealed that Luther was not alone.

This unsettling discovery prompted her to seek greater knowledge of Judaism, about which she knew little, despite the fact that her father was from an assimilated Jewish family. Although he had converted to Catholicism in her youth, she knew her relatives were Jews and that an aunt had perished in Auschwitz. Her father, too, would likely have been killed had he not been able to get a visa to the U.S. In the Third Reich, a Jewish convert to Catholicism was still a Jew.

During her Marquette years, Fleischner began an intense study of Judaism and of the Holocaust, completing her degree in 1971 with a dissertation on Judaism in German Christian Theology Since 1945. Appointed as a professor of religion at Montclair State College (now University) in 1972, she developed a course on the Holocaust that she taught regularly for nearly 20 years — long before such a course became common.

Fleischner had a major role in the planning and implementation of an international symposium on the Holocaust held in June 1974 at New York City's Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine, editing its presentations in a 1977 collection, Auschwitz: Beginning of a New Era? Reflections on the Holocaust.

In the 1980s Fleischner went to France to interview three French Catholic women involved in the resistance to Nazism and rescue of Jews. In a lecture on "Memory of Goodness," at a conference in Oxford in 1988, she said that these interviews were good for her to " 'touch,' as it were, goodness within my tradition." Such encounters, she added, proved healing and counterbalanced the heavy burden of "prejudice, cowardice and betrayal within my Roman Catholic tradition."

Eva Fleischner, in a screenshot from "In Search of the Grail: The Story of a Women's Movement" (NCR photo/YouTube)

In 1999, Australian Cardinal Edward Cassidy appointed her to the six-member International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission to undertake a review of Vatican archival material from 1939-1945. The commission's mandate involved the sensitive matter of assessing 11 volumes of documentation pertinent to the papacy of Pope Pius XII.

Their report, presented in Rome in November 2000, raised 47 substantive questions that should be pursued, and identified other sources that would provide a more comprehensive analysis of the role of the Vatican during the Holocaust.

Their concluding counsel that "openness is the best policy for a mature and balanced historical assessment" has at last been heeded: Pope Francis announced in March 2019 that the archives pertaining to 1939-1958 would be fully opened on March 2, 2020.

The archives did indeed open, only to be closed on March 6 by the pandemic that ravaged Italy and has continued its destructive path across the globe. The archives are scheduled to reopen following the traditional summer recess.

I knew Eva Fleischner primarily through our shared membership in the Christian Scholars Group on Jews and Judaism (she became a member in 1972, I in 1988) and on the Committee on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

It is no exaggeration to say that we revered her — not simply for the sharpness of her intellect but also for the fierceness of her passion and the depth of her person.

She is indeed a "memory of goodness." As Jews say, "May her memory be a blessing."

[Mary C. Boys, a member of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, is the Skinner and McAlpin Professor of Practical Theology at Union Theological Seminary.]