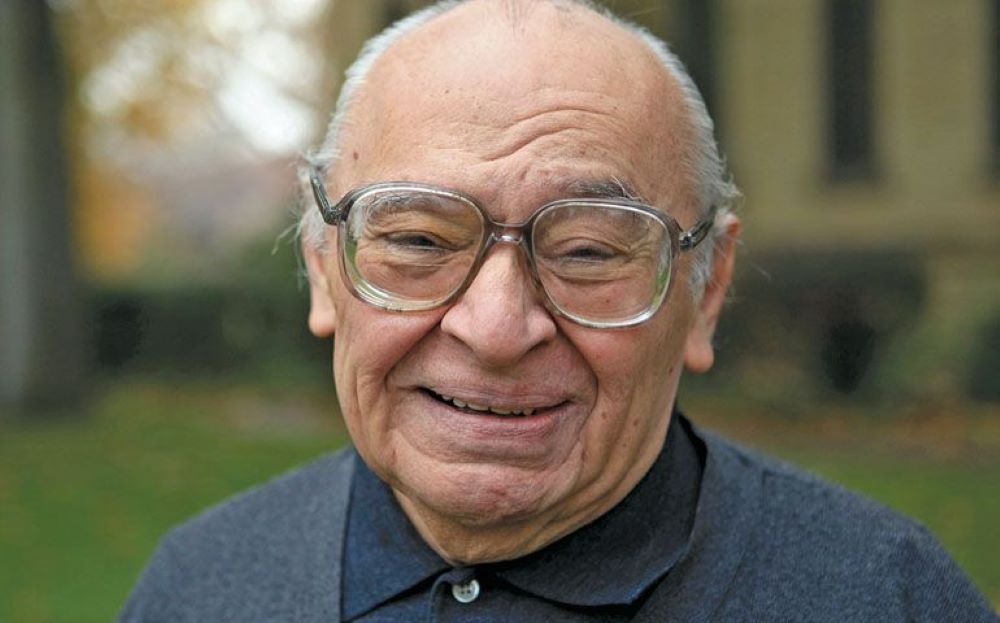

Dominican Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez (CNS/Courtesy of the University of Notre Dame/Matt Cashore)

It would be tempting while reflecting on A Theology of Liberation, the 1971 book by the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, to compare it to a couple of musicals from that same year: the Broadway opening of "Jesus Christ Superstar" and the off-Broadway debut of “Godspell.”

After all, Jesus does figure prominently in all these works. However, while the musicals served up modernized takes on Jesus and his followers, if the idea is that Gutiérrez's text was simply a way to update a Latin American Jesus — the son of God wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt — then that misses the enormous contributions of this landmark work.

No, the better cultural metaphor from 1971 is Marvin Gaye's album "What's Going On?" For just as Gaye broke away from the formulaic Motown hit machine to explore themes like the Vietnam war, poverty and the ecological crisis, so Gutiérrez forced Christians to hear the voice of God among the world's suffering and to ask whether the church's talk of salvation meant anything for their liberation.

That this book would spawn perhaps the most influential, and most controversial, theological movement in the last half century is a bit of a surprise. The book has no inflammatory passages. It does not call for armed rebellion. Nor does it engage in the kind of polemical attacks that pass for public discourse today. Yet, in the way that it offers both a diagnosis of our world's ills and a vision for the way that the church can help transform them, A Theology of Liberation remains as relevant today as it was half a century ago.

Advertisement

Gutiérrez, a Dominican priest now 93, wrote the book after the Second Vatican Council, when much of Catholic theology was moving away from the deductive style of an earlier generation (like the Baltimore Catechism) to an inductive one that took human experience into account. However, there was still something missing. Although the council had done much to recognize people of other faiths and indeed of no faith at all, it only dimly realized the plight of "non-persons" that today still make up the majority population of the planet. Liberation theology challenges all God-talk by placing their experiences at the center of reflection.

If there is one thing we have learned in the last few years, it is that the great problems that we face, such as racism, poverty and the climate crisis, are structural in nature. They have long histories and are embedded socially in ways that are often masked in day-to-day life. A Theology of Liberation takes that structural insight to engage with and deepen Christian theology.

Take, for example, sin. If sin merely connotes violations of personal and interpersonal moral conduct, then it cannot account for the Shoah, the Middle Passage or the conquest of the Americas. It is not that personal sins don't exist or aren't important, but if Christians don't account for these great social sins, then they aren't able to address significant ways that the world contradicts God's will for human and planetary flourishing.

Sadly, as Gutiérrez surveyed the history and theology of Christianity since Columbus' arrival, he realized that the church's message of salvation too often did not address this deep sense of human liberation. Indeed, history showed a church that either ignored worldly suffering altogether or considered it to be merely a vale of tears on the journey to the eternal. In the meantime, it protected itself by legitimizing powerful elites in the interest of keeping the status quo.

If that sounds a lot like the "pie in the sky" religion critiqued by Karl Marx, then one begins to understand affinities between Marxism and liberation theology. However, it is wrong to equate them. Though Gutiérrez would engage with some of the political and economic diagnoses of certain Marxist thinkers at that time, his work is based on another source altogether — the Bible.

As theologian Gaspar Martinez has noted, A Theology of Liberation cites 45 different books of the Bible for a total of 405 references. Though the "communist" label served as a convenient epithet, the vehement and often violent opposition to liberation theology stemmed from the uncomfortable truths this scriptural turn revealed. Like the opposition to critical race theory today, it is unsettling to have the history and reality of an institution questioned from within. Like Moses, the prophets and Jesus himself, liberation theology denounced tyrannies that meant bondage for so many.

As powerful as its prophetic critique is, A Theology of Liberation also presents a positive vision summed up in a most basic definition of salvation — communion with God and with others. Yet that simple phrase yields deep implications when it takes seriously what is going on in the world and how it might affect the way core Christian beliefs are understood.

The vehement and often violent opposition to liberation theology stemmed from the uncomfortable truths this scriptural turn revealed.

Liberation theology would be easy to dismiss if it simply abandoned the Christian tradition. But it isn't a question of Jesus as a Liberator vs. Jesus as the God-human. The challenge of liberation theology is to understand Jesus as God-made-flesh and then to ask how the church can be more like Jesus and incarnate itself in the world. No, not in the centers of power and wealth but in the peripheries that long to hear good news.

Indeed, for so much talk about secularization as the great challenge to faith today, a theology of liberation suggests that it is idolatry more than disbelief that is our great challenge. Catholicism that coddles up to corporate and political elites is much more a pseudo-religion then one that marches in protest to human rights violations and systemic racism.

This signals another great insight in Gutiérrez's book: There is a close connection between the church's self-understanding and how it acts in the world. This is no mere abstract idea. If the world does not matter, or even worse, if it is to be disdained, then there is no reason for the church to show mercy or address its problems. It can arrogantly proclaim that "outside the church there is no salvation," and busy itself with its own power and interests.

Gutiérrez recognized that the understanding of church (ecclesiology) is tightly connected to doctrine, worship and pastoral practice. This is why, for example, we must see that the Latin language Tridentine Mass is not merely one item on a liturgical menu of choices today. It is part of a larger theology and worldview that the church no longer holds.

Though Gutiérrez could draw upon several images of the church coming out of Vatican II, such as "people of God," he develops the image of the church as the "sacrament of salvation." Key to this image is the way that a sacrament not only points to something deeper, it makes it present.

Jesus preached and made present the reign of God. The church must then, in solidarity, faith, hope and love, do the same. As the sacrament of salvation, the church strives to make present a communion with God and with others. It is not a gatekeeper. It does not seek to exclude. Rather, it should strive to overcome barriers and be a vehicle for inclusion and communion among all people.

Fifty years is a long time, and the history of liberation theology is filled with highs and lows. It has been praised and embraced around the globe. It has been lambasted and caricatured too. Many martyrs have paid the ultimate price in following its gospel call.

Sometimes its "friends" who claimed to be inspired by it understood it less than its opponents. Its death has been declared prematurely far too many times. Yet, one thing remains clear. A Theology of Liberation demonstrates the power of faith when it honestly and courageously addresses what's going on.