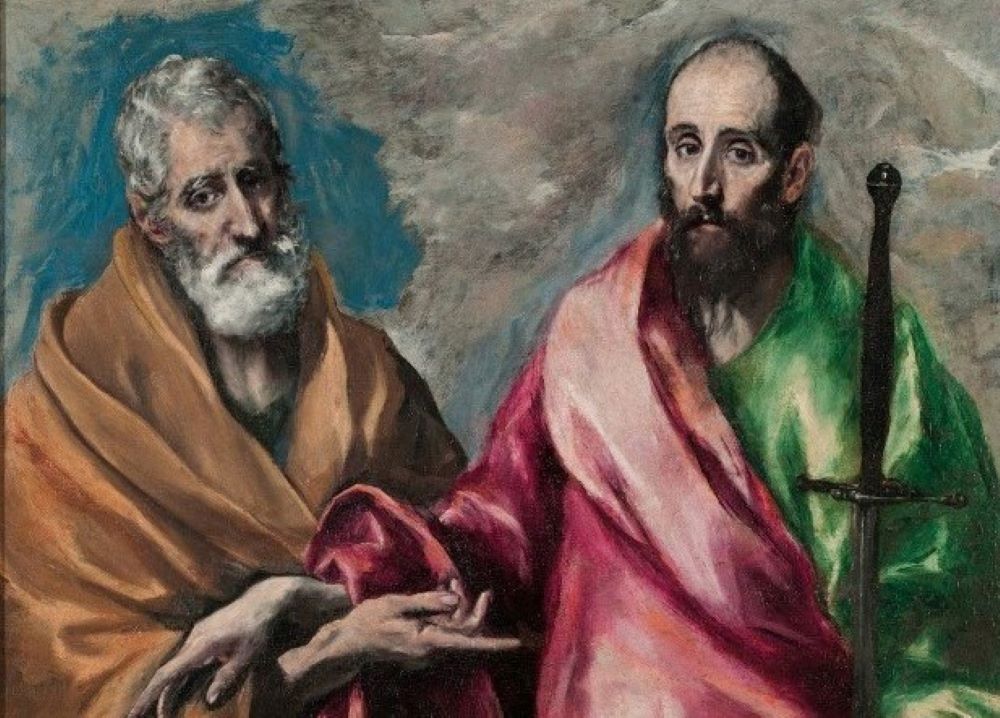

A section of the painting "St. Peter And St. Paul" (1590-1600) by El Greco (1540-1614) (Artvee)

June 29 marks the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul. The New Testament, of course, portrays Peter as a Galilean Jew, a fisherman, who became an early disciple of Jesus. He is remembered as being foremost among the Twelve, as having a flash of insight about Jesus at Caesarea Philippi, and as championing news of Jesus' resurrection in the early church, despite having earlier denied knowing him three times. Peter left behind no personal writings. (The 1 and 2 Letters of Peter are universally regarded as written pseudonymously after Peter's death.)

In contrast, the New Testament includes several epistles authored by Paul himself. They reveal a Jew from the Mediterranean diaspora whose native language was Greek. He writes of himself as a Pharisee with great zeal for the Torah who, for reasons he does not explain, was a violent foe of the preaching of Jesus' resurrection until God revealed the raised Jesus to him, calling him to be an apostle with a mission to Gentiles (Phillipians 3:3-6; Galatians 1:13).

Paul's letters, however, are "hard to understand" (2 Peter 3:16). Their inherent complexities became more confusing over the centuries when millions of Gentile Christians (mis)read Paul with false ideas about Judaism in their minds. Especially after the Reformation, many presupposed that the Jewish dedication to observing the commandments in the Torah (the mitzvot) was a vain, legalistic effort to earn God's favor. With this premise, Christians readily imagined that Paul had come to see Jewish practices as futile and replaced by the "law-free" Gospel of Christ.

The author — possibly a Gentile — of the Acts of the Apostles, writing 30 or more years after Paul, contributed to this caricature by having Peter describe the Torah "as a yoke that neither our ancestors nor we have been able to bear" (Acts 15:10). In contrast, however, Paul himself described his own Torah observance as "faultless" or "blameless" (Philippians l 3:6; Luke 1:6). He nowhere writes that Jews should cease Torah observance, including after baptism into Christ — something that Acts also concedes elsewhere in that book (Acts 21:17-26 and 16:1-3).

In fact, as E.P. Sanders demonstrated in his landmark 1977 book, Paul and Palestinian Judaism, Jews in Paul's era were devoted to the Torah — not to win God's love — but out of gratitude for God's loving gift of the Torah to guide them into lives of holiness. Paul's Jewish contemporaries observed the Torah and discussed the best interpretation of its mitzvot as the proper response to the God who loved them and chose them for covenant. There is no evidence from the period that Jews thought this covenantal duty was onerous.

To fully understand Paul, readers today need to appreciate that he saw himself as a "Jew by birth and not a Gentile sinner" (Galatians 2:15). His letters were addressed to non-Jewish Gentiles who had become believers in Christ but were insecure about their standing with the God of Israel. It was they who needed Paul’s assurances that they could be holy without taking up observance of the Torah, which was God's gift to Israel alone.

In Galatians, Paul wrote that before coming to know Christ he had attacked those fellow Jews who proclaimed that the crucified Jesus had been raised. But now he himself had become an apostle or messenger of that good news (Galatians 1:23). That change of heart made him a different kind of Jew, not a non-Jew. He was now Jewish "apostle to the Gentiles" (Romans 11:13; Galatians 1:16; 2:2).

Reading Paul as he saw himself, as a Jewish apostle and not a Jewish apostate, changes how almost all his words are understood. A vivid example can be seen in Galatians 1:13. Rather than "you have heard of my former way of life in Judaism (Paul as apostate)," the verse is better read as "you have heard of my former way of life in Judaism (Paul as apostle)." He was now messianically enthusiastic.

Relatedly, many Christians today hold the erroneous notion that Paul had "converted" from "Judaism" to "Christianity" and thus saw no value in Judaism after Christ. In this view, Paul was an apostate from Judaism. However, and tellingly, the words "Christian" and "Christianity" appear in none of his letters. During Paul's lifetime a distinct "Christian" religion did not exist. This should alert readers today that he did not think in the same categories we do.

His experience of Christ also convinced Paul that "the present form of this world is passing away" (1 Corinthians 7:31). The cosmos was in a process of transformation, which in his earlier letters he expected would climax during his lifetime (1 Thessalonians 4:15-17). Perhaps influenced by one stream of contemporary Judaism, he anticipated that when the messiah came all pagan idolaters would be doomed (1 Thessalonians 1:9-10; 4:1-8, 15-17). Paul now believed that God had recently revealed the identity of that messiah by raising the crucified Jesus to transcendent life (Romans 1:4).

As apostle to the Gentiles, Paul thought it was his duty to rescue as many idolatrous non-Jews as possible from being condemned at Christ’s imminent return in glory and judgment. So deeply does he feel for the Gentiles' plight that he often uses the rhetorical device of identifying with them by using the first-person in writing to them, e.g., "If we live by the Spirit, let us also be guided by the Spirit" (Galatians 5:25). Paul's driving conviction was that non-Jews must turn "from idols to serve a living and true God" (1 Thessalonians 1:9), the One God of Israel, in order to be made righteous ("justified") before the imminent End.

This is all foreign to Christians today who do not share Paul's urgency that "the appointed time has grown short" (1 Corinthians 7:29). Neither do they see humanity as Paul did, divided into only two groups: Jews in covenant with God and non-Jews "who do not know God" (1 Thessalonians 4:5). To put it bluntly, Paul did not imagine he was writing to “Christians” thousands of years later who constituted a separate religious community. He wrote to former pagans who had come to know the God of Israel (or "to be known by God" – Galatians 4:9) through Christ.

With the raising of Christ, Paul believed that Israel’s covenanting with God was coming to its telos (Romans 10:4), its ultimate divinely intended global goal. God's promise to Abraham that he would be father of many nations (Genesis 17:4) was coming to pass for Paul. Gentiles could now become "Abraham's offspring, heirs according to the promise" (Galatians 3:29; cf. Romans 4:11-18), but as non-Jews. For Gentiles to become Jews by being circumcised would be nothing new; that had always been possible. And if they did, they were "obliged to keep the entire law” (Galatians 5:3).

Advertisement

For Paul, however, there was now an entirely new situation, one that fulfilled what God had promised Abraham. By putting aside idolatry and "putting on Christ" (Romans 13:14), pagans could be found righteous before the God of Israel. But they had to remain Gentiles or the only people worshiping God would be Jews. In that case, Paul thought, "Christ [would have] died for nothing" (Galatians 2:21). In short, Paul was a messianically-enthusiastic Pharisee who reached out to save Gentiles from the curse he believed they were under because of their idolatrous and evil practices. Consistent with the Pharisaic desire to spread holiness, Paul saw himself as promoting holiness even among pagan Gentiles.

In Romans 9-11, Paul writes of his yearning for his fellow Jews to agree that the time for the Gentiles to turn to the God of Israel (e.g., Isaiah 2:1-4) had arrived because of the raising of Christ. He insists, in words often ignored by later Christian readers, that God has not rejected the Chosen People (Romans 11:1-2), that they have not "stumbled so as to fall" (11:11) and he speculates that his present situation is all God's doing. Nevertheless, "all Israel will be saved … for the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable" (11:26, 29).

At the same time, while trying to persuade Gentiles who were infatuated with the "trappings" of Judaism that the Torah was not meant for them, Paul made comparisons that later Christians read as advancing their view of Paul as a Jewish apostate. For instance, in 2 Corinthians 3, he writes that the people of Israel have a veiled reading of the "old covenant" (3:14). Moses' ministry (not covenant) came in a blinding glory that condemned idol worship and exposed the depravity of pagans, but this "ministry of death" for pagans is now rendered powerless by the even more brilliant glory of the ministry of the Spirit that raised Christ, the ministry that Paul exercises (3:7). But for most Jews, Paul suggests, the genuine light and glory of the Torah is so engaging that they do not see the even brighter, End-times glory of Christ.

Without a grasp of Paul's worldview, later Christians easily misconstrued what he felt was at stake. To see Paul as he saw himself, as a Jewish apostle — not a Jewish apostate — Christians today must learn to read his epistles with new eyes, as when an optometrist switches lenses and murky letters on a screen suddenly become clearer. Then they can more faithfully adapt Paul's first-century inspired insights into the very different contexts of the 21st century.