U.S. Army chaplain Father Emil Joseph Kapaun, who died May 23, 1951, in a North Korean prisoner-of-war camp, celebrates Mass from the hood of a jeep Oct. 7, 1950, in South Korea. (CNS/Courtesy of U.S. Army medic Raymond Skeehan)

As Holy Week was approaching, identification of the remains of Fr. Emil Kapaun — a Catholic chaplain in the 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, during the Korean War, who died in an icy cold, lice-infested North Korean prisoner-of-war camp — seemed like a divine plan.

With thousands of others deemed "unaccounted for," Kapaun was believed to have been buried in an unmarked grave by the bank of Yalu River.

However, recently the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency matched Kapaun's dental records and DNA provided by his younger brother Eugene with remains buried in Hawaii, specifically the National Cemetery of the Pacific.

President Barack Obama had awarded Kapaun the Congressional Medal of Honor on April 11, 2013, for the gallantry and bravery he showed to his comrades during the Battle of Unsan (Nov. 1-2, 1950), days before the Chinese Volunteer Army entered into the war theater "uninvited."

Fr. Kapaun's nephew, Ray Kapaun, received the award for his uncle at the White House. The medal citation reads: "Chaplain Kapaun calmly walked through withering enemy fire in order to provide comfort and medical aid to his comrades and rescue [the] wounded from No-Man's Land."

No one would have heard of this fearless and compassionate priest who died in that hidden village, in the hermit kingdom of North Korea's POW camp, but like all those extraordinary men in history, the witnesses of the great soul told and retold how he made a difference in countless lives.

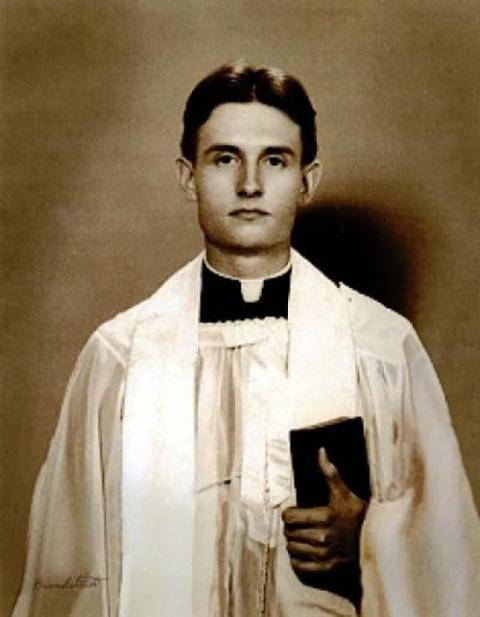

An undated photo of Fr. Emil Joseph Kapaun, a Kansas priest and a military chaplain who died in 1951 ministering to prisoners of war during the Korean War (CNS/Courtesy of The Catholic Advance)

In Kapaun's case, his fellow prison inmates told of their fearless chaplain who laid his life before his injured combat buddies on the battlefield, and later, for his sick and dying inmate brothers in the dreadful prison camp.

On March 25, 1951, Kapaun celebrated his last Easter Sunday Mass in a war-damaged Christian church near the POW camp. The five months of starvation diet (cracked corn, millet and watery soup) had taken a toll on every prisoner in the camp.

But they were also punished for not having swallowed communist propaganda, and were forced to stand outside in minus 30-40 degrees, making them sick with pneumonia. Those who had not died yet were gravely ill. Unfortunately, Kapaun was no exception.

That Easter Sunday, he stood before a congregation made of about 60 gaunt and foul-smelling POWs from different religious faiths — some wore dirty, tattered American uniforms, some wore British uniforms, others simply wore whatever garments their captors have given them. Since they had arrived there, after a long and agonizing death march — a stretch of 85 miles on snow-covered mountain terrain — no bathing privileges were given. Some also had skin diseases that went untreated.

According to William Maher, author of A Shepherd in Combat Boots, Kapaun looked worse than most men in the congregation. He wore a black patch on one eye due to infection after a chip of wood had damaged it, and used a homemade cane when he walked because of the blood clot in his leg, which no one knew about. Still, he had made a small crucifix with scrap pieces of wood and carefully set it at the center of the altar table cleared of the debris.

That Easter Sunday, service was only possible because of the recent modification to the restrictions regarding religious activities in the POW camp. To prepare for this grand event, his last Easter Sunday, the chaplain led a few prisoners to church the previous day, despite his weakened physical condition, and together, they cleared heaps of broken and charred roof tiles, windowpanes, wood panels, and various debris to make room for his congregation.

There was no music prepared for this Easter Sunday service. The theme of his sermon was suffering and the Crucifixion. He didn't utter a word of the risen Christ or glory that followed. The congregation quietly listened, reflecting on the suffering they themselves had endured and what they had witnessed from their lost inmate-brothers, finally grasping the gravity of Jesus' suffering and crucifixion they had not understood before.

Unexpectedly, someone sang the Lord's Prayer, and many joined him. When finished, a chorus of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," sung by the Americans, echoed through the damaged church.

"Mine eyes have seen the glory / Of the coming of the Lord ... Glory, glory, Hallelujah! / His truth is marching on."

The Mass ended with the baptism of a prisoner. The man had confided in Kapaun earlier that he had wanted to become a Catholic, and the chaplain chose this special occasion to grant his wish.

Afterward, men shared with one another what this Mass meant to them, and how special it was after having lived in the hellish prison for months. But the chaplain broke into tears, surprising them all. When one of them asked why, Kapaun responded that it hurt him for not having served them holy Communion.

Advertisement

Two months later, on May 23, 1951, Kapaun died alone in what the Chinese captors called "the Hospital," an abandoned, dilapidated Buddhist temple on the top of a hill where the communists sheltered their hopelessly ill prisoners. No visitors were allowed.

It was two or three days after Kapaun's close friends carried him there on a stretcher that they received the chaplain's final blessings. He followed it with a promise: "When I will be up in heaven, I will say a prayer for your safe return home."

In Maher's description, as the tearful comrades were about to leave the Hospital, they saw their chaplain looking up at the Chinese guard who came to get him. One of them told the others, later, that he had heard the chaplain whispering: "Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they're doing."

Seventy years later, having lost over half a million Americans to COVID-19, and with 30 million having been in combat with the virus, this Easter Sunday holds many questions for Americans. For more than a year since the coronavirus landed in the U.S., we have been ordered to "stay at home."

Many people could not visit their dying parents, spouses and relatives in hospitals or in nursing facilities. Some churches are still closed. Schoolchildren, too, were ordered to stay at home, and attended Zoom classrooms rather than real ones, thus isolating them from their classmates and teachers. Many people lost their jobs, forcing them to move in with others or further depend on government assistance.

In addition, Americans suffered moral injustice caused by the outgoing former president who refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the newly elected President Joe Biden. Donald Trump incited frustrations and doubts about the future of America, "the republic for which we stand, one nation under God."

Today, given our circumstance and the coming Easter Sunday, America needs God's healing grace more than ever. We must understand what Jesus went through — his suffering, his unimaginable pain, his humiliation and his death on the cross.

Kapaun's last Easter Sunday in North Korea not only speaks to us about what he and his inmate brothers went through, but leads us to a deeper understanding of Jesus' suffering and death on the cross before his resurrection.