A statue of Franciscan Fr. Junípero Serra is seen outside Mission San Gabriel in San Gabriel, California, in 2018. (Wikimedia Commons/Wraithwriter77)

What wasn't said was as important as what was.

In his Sept. 8 homily to launch a Jubilee Year marking the 250th anniversary of the San Gabriel Mission, Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez spoke of his effort to imagine the choices faced by Junípero Serra and the Franciscans who founded the California missions.

"I wonder what it felt like for those missionaries — leaving behind their homes and families, knowing they would never be coming back," Gomez said. "What would cause someone to set out for a place they have never seen, to serve a people they do not even know?"

Tongva tribal members had begun the outdoor service with incense, flute and incantation on a temperate late-summer evening outside the founding mission of the archdiocese in the now-suburban San Gabriel.

But it was as if the Indigenous were accorded a ceremonial presence but not a substantial one. Gomez finished musing on the hard choices of the missionaries and moved on. He made no mention of the choices faced by the Indigenous in the time of Serra as they contemplated the offer of Christian faith conditioned by the coerced loss of their land, way of life and culture.

To be Catholic in California today is to hunger for the church to take the lead in openly facing its problematic mission past. The jubilee year in the Los Angeles Archdiocese — set to go until September 2022 — does not appear thus far to be a vehicle for such an accounting. It has a worthy goal: renewing faith in a missionary spirit. But it remains within the framework of personal piety alone, not historical redress.

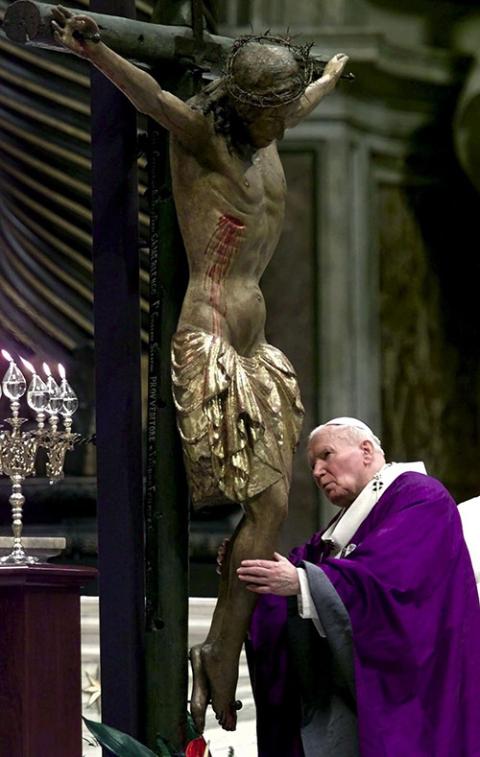

Pope John Paul II embraces the crucifix in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican March 13, 2000, during a liturgy in which he asked forgiveness for past and present sins of Christians. (CNS/Reuters)

There has to be a better way. Inspired by an initiative at the Los Angeles Catholic Worker, I would like to propose five ideas toward a better jubilee year. (I am living this fall at the Catholic Worker but am not speaking here on behalf of the community.)

I have especially been influenced by Pope John Paul II's remarkable jubilee year in 2000, when he apologized on behalf of the church for numerous historical misdeeds. The Los Angeles Archdiocese notably did not follow John Paul II's model.

In any case, more jubilee years may be coming as other missions mark 250 years since their founding (for instance, San Luis Obispo in 2022). We should approach such occasions ready to redress the past.

1. The spiritual is in the messiness of the material

I noted the readiness of Gomez to reflect on the choices of the missionaries but not on those of the Indigenous. Three days after the service at the San Gabriel Mission, this tendency was evident again.

At the Mass opening the jubilee year at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Angels in downtown Los Angeles, the first reading from Leviticus proclaimed the biblical meaning of a jubilee year with piercing clarity: "It shall be a jubilee for you: you shall return, every one of you, to your property and every one of you to your family."

Truer words could hardly be spoken about the moral imperative of a jubilee year focused on the Indigenous past in California and its history of stolen land and family separation. But no one responded to the challenging words for the rest of the Mass, which was dedicated to the encouragement of personal spiritual renewal.

As we face our difficult past, we cannot sequester the spiritual away from the messy realities crying out for restoration.

2. Franciscan Fr. Junípero Serra is a culture war distraction

On Sept. 24, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law that mandates the removal of a statue of Serra from the grounds of the state capitol. Gomez and San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone published an opinion article in The Wall Street Journal decrying the bill and arguing that "no serious historian" agrees with the legislative language, which states: "Enslavement of both adults and children, mutilation, genocide, and assault on women were all part of the mission period initiated and overseen by Father Serra."

Here it is important to separate two issues. One is the complex question of the precise degree of accountability that Serra had over the mission system that he founded and that continued long after his death. Does the new California law assume too much and the archbishops too little?

The question is a distraction from the issue that really matters: the effects of the mission system on the Indigenous.

Moreover, we are faced with the incoherence at the heart of a culture war crusade: The people decrying the removal of statues of Serra as a violation of religious freedom are crickets when it comes to the manifold ways in which the mission system compromised the religious freedom of the Indigenous.

Advertisement

3. Accountability exists in systems

In his 2007 volume California: A History, the late California state historian Kevin Starr said: "It is difficult ... to see the mission system as resulting in anything other than wholesale anthropological devastation, whatever the sincerely felt evangelical intent of the missionaries."

It is difficult to pinpoint accountability when speaking of systems. But it is also incorrect to dismiss the possibility of accountability in such matters. For instance, the Catholic Church acted as an agent of the Spanish Empire in the creation of the mission system.

"The missions were intended to secure California for the Spanish crown," a group of Santa Clara University scholars wrote in 2020. Can such collusion between church and crown be understood simply as the missionaries ameliorating an imperial ambition that was going to seize Alta California one way or the other? This is too easy of an out. In a time of rising religious nationalism, we need a broader understanding of the costs to the Catholic faith that resulted from such systemic collusion with the crown.

4. Responsibility and the mystical body of Christ

Were the missionaries accountable for the wrongdoing of the mission system? Is the church today accountable for deeds so long in the past? These questions hover over this and any would-be jubilee year. But, in a sense, these questions are missing the point — at least from the perspective of faith.

Subjective culpability is crucial. But objective wrongdoing remains the responsibility of the people of God, whether subjective culpability is established or not. The Vatican document providing the theological justification for John Paul II's jubilee year in 2000 makes this clear: Our efforts to redress the past are based on "the bond which unites us to one another in the Mystical Body, all of us, though not personally responsible and without encroaching on the judgement of God, who alone knows every heart, bear the burden of the errors and faults of those who have gone before us."

5. The Indian Christ

In 1989, John Paul II met with the Indigenous of present-day Argentina. They told him: "We were free, and the land that was the mother of the Indians was ours. We lived from what she gave us generously, and we all ate in abundance. ... Until one day European civilization arrived. It planted the sword, the language, and the cross and made us into crucified nations. ... In that cross, they [the Europeans] changed the Christ of Judea for the Indian Christ."

The Catholic Church in California today needs to hear the story of the crucified Indian Christ.