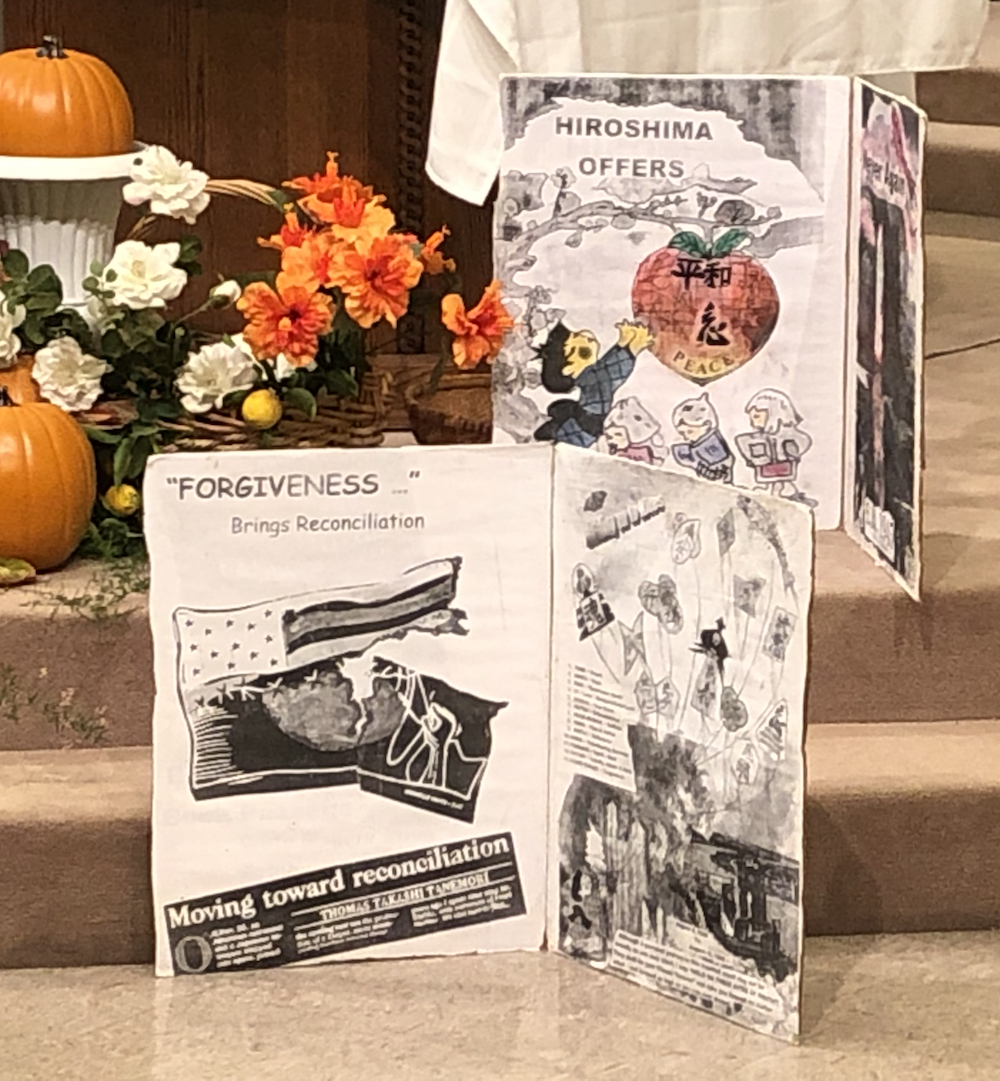

Signs designed by Elizabeth Weinberg calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons are displayed at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Oakland, California, Nov. 23. (Tom Webb)

Takashi Tanemori distinctly remembers the intensity that characterized the lessons both of his parents gave him on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, in Hiroshima. He was 8 years old, and his father had repeatedly instilled in him the lessons from the Samurai code, or Bushido. In short, his father taught him the greatest victory is not over others but over the weaknesses within one’s self. He reiterated that genuine giving was not done from abundance but from the depths of oneself. Furthermore, the importance of personal integrity was highlighted, especially in the pursuit of truth. He was instructed to never allow his hands to remain idle. Finally, the greatest quality one could possess was dependability, so people were always aware that you could be counted upon. He recalled that his father wore a notable and inexplicably worried look that morning.

Takashi Tanemori tells his story of survival after bombing of Hiroshima. (Tom Webb)

Takashi was preparing to leave for school at 7:31 a.m. but noticed his mother gently sobbing while she rocked her youngest child. He recalled how unseemly her tears were since it was the first time he had ever seen her weep. She gently repeated what his father had taught him and emphasized that he was the "number one son," heir to a Samurai family. Her tears continued to flow and she asked him to wait just a little longer before he departed for school. Shortly after, he announced to his mother he was leaving for school.

Within one hour, Takashi would lose both his parents and two of his sisters as the atomic bombing of Hiroshima began. Only 2% of those living within the vicinity of ground zero survived. For the next eight years Takashi would live as an urchin on the streets, begging and rummaging for food in the garbage.

He spoke at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Oakland, California, at a Liturgy of Memory and Repentance for Victims of Nuclear Attacks and Nuclear Accidents.

Stories such as those told by Hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki), the Roman Catholic traditions evolving stance on the morality of nuclear weapons, and the origins of Pax Christi in 1945 inspired members of Pax Christi Northern California to discuss and organize the Nov. 23 liturgy.

Pax Christi began as a prayer crusade in France in the waning days of World War II in March 1945 as part of a larger effort organized by Bishop Pierre-Marie Théas of the Montauban Diocese following his eight-month stay in a German concentration camp, and Marthe Dortel Claudot, an educator who sought reconciliation and peace between French and German Catholics. Baptized in a flat in Montauban, the fledgling movement utilized weapons of the spirit such as prayer, Stations of the Cross processions and symbolic exchanges of chalices, liturgical missals and bells between French and German Catholic parishes to replace items destroyed in the bombing raids and wartime chaos.

Pax Christi International now has more than 120 chapters in 60 countries, non-governmental organization status at the United Nations and standing in the European Union, and it is engaged in various facets of reconciliation — peacemaking with justice on a wide variety of issues across five continents.

If prayer is the foundation upon which Pax Christi is based, so, too, is the evolving Catholic position on war and peace.

Advertisement

In the case of nuclear weapons, a certain horror has characterized the church"s position. Well-known people, movements and events have been benchmarks of this position. These include virtually all popes since Pius XII, Dorothy Day and other members of the Catholic Worker movement, Archbishop Fulton Sheen, Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton, Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan and his brother Philip Berrigan, the Second Vatican Council, the Plowshares movement, and episcopal leaders like Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, Bishop Leroy Matthiesen. The U.S. bishops" conference, Vatican statements and secular diplomats have maintained a remarkably consistent, if not nuanced, position about the morally questionable foundations of nuclear weapon stockpiles and the ongoing development of nuclear weapon technology. The U.S. bishops" pastoral letter of 1983, "The Challenge of Peace: God's Promise and Our Response," specifically called for some form of U.S. apology for the destruction caused by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

By 2015, it became increasingly clear that the end of the Cold War hostilities had not led to the abolition of nuclear weapons. While there is a grateful recognition that the actual number of nuclear weapons has diminished, the threat of nuclear weapons themselves continues. Advances in nuclear weapons technology, a renewed arms race between the U.S. and Russia and evidence that the strategy of the "mutually assured destruction" doctrine, once believed to have credibly reduced the spread of nuclear weapons, has inversely and perversely given credence to countries like India, Pakistan and North Korea to develop their own nuclear stockpiles.

Oblate Fr. Jack Lau presides at Liturgy of Memory and Repentance for Victims of Nuclear Attacks and Nuclear Accidents. at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Oakland, California, Nov. 23. (Tom Webb)

Joining a growing international collection of voices including the United Nations, notable non-governmental organizations like the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and others, the church"s position now labels any national development and ownership of nuclear weapons as immoral.

In what is hoped to be the first of an annual liturgy for victims of nuclear weapons attacks and accidents, the weekend of Nov. 23-26 produced liturgies of solidarity with Pope Francis’ visit to Japan.

The purposes of the liturgy itself are several fold. By remembering the victims of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the multiple victims of nuclear weapons-related accidents around the world since that time, it is hoped that participants may be inspired to either continue or re-engage in the church"s long effort toward promoting the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Takashi Tanemori since 1985 has immersed himself in a spirituality of forgiveness and reconciliation for the victims of Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima and Nagasaki through his Silkworm Peace Institute. Now gradually growing blind because of the effects of the radiation he experienced during the bombing of Hiroshima, he speaks publicly in a variety of settings, like schools, faith and civic groups and artistic exhibits.

His devoted assistant, artist Elizabeth Weinberg, sees one hope for the future: "Ground zero for forgiveness is the human heart."

[Tom Webb is a member of Pax Christi Northern California's regional council.]