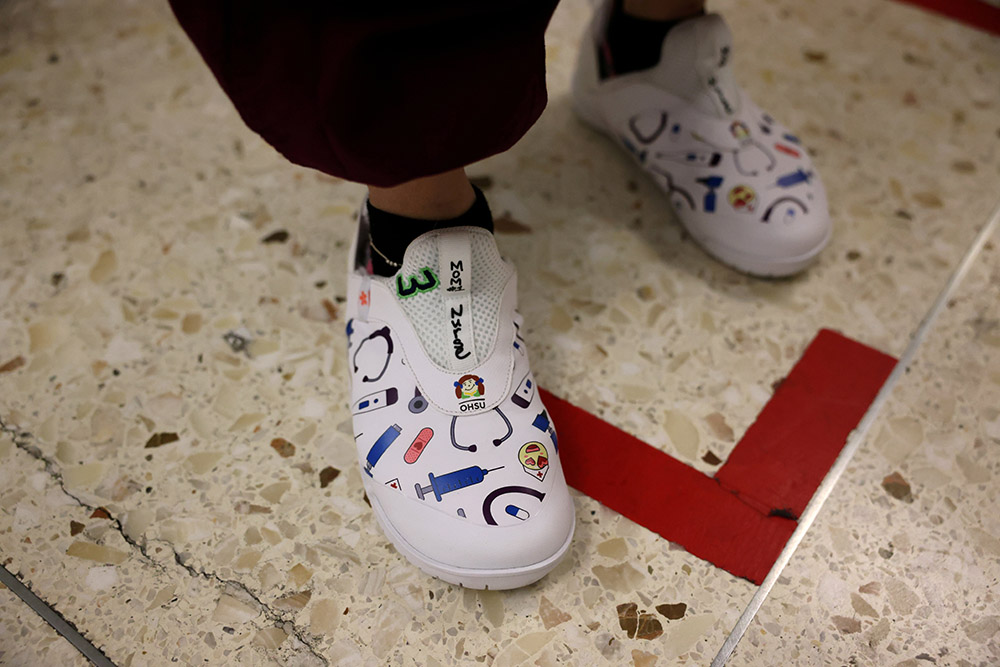

A nurse's shoes are seen in the COVID-19 intensive care unit at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, California, Nov. 19, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

As a teenager in the 1970s, I knew with certainly what I would not become: not a nun and not a nurse. As I chafed under the weight of a post-Vatican II Catholicism still rigid with restrictive limitations and was captivated by second-wave feminism, there were to be no gender-determined roles for me. No subservience. I swore this to myself and to the ancient goddesses making a cultural comeback.

I left the Catholic Church in my late teens, returning a few years later, after my mother's death. I couldn't exactly pray, but I found solace in the Madonna's cavernous chapel on my university campus.

After a decade of working to address the church's unrelenting patriarchal oppression and exclusion through groups such as Women Church, Chicago Catholic Women and Call to Action, I fled once again. On the steps of Chicago's Holy Name Cathedral with my son, Gabe, on my hip and my daughter, Grace, by the hand, we gathered in witness of the ordination of yet another batch of young men, and I bid the Catholic Church farewell.

I found my way to the Quakers. There I remained for 20 years. Until I came back, again.

During this second sabbatical, I also became a nurse. I could not logically explain this impetuous decision born of pure intuition. Only many years later, when I learned about hospice care, could I articulate what I had known instinctively: Nursing practice unfolds at the epicenter of our humanity. It is raw and it is tender, the impact indelible.

But I knew none of that till much later. In the early days of my education in one of the few remaining diploma programs in a Catholic hospital, I knew only a nightmarish sense of déjà vu, with flashbacks to my former stint in a Catholic girls' high school with linen uniforms and habited nuns and gloomy statues and punishments for the most trivial of infractions. There were no priests, but there was a reigning cardiac surgeon for whom our faculty demanded we stand until his departure.

This was in the late '80s, two decades after both Vatican II and the crest of feminism's second wave. I was 38 years old with a graduate degree in English Lit, 10 years of direct social service, expecting my third child. I was caught in a time warp — standing, genuflecting to male authority. It made no sense. Having become a nurse, was the convent also in my future?

It was strangely familiar, this denigration of female wisdom and power. It reminded me of nursing, circa 1970s. A religious version of Brigadoon — lovely and beckoning but strangely untouched by time, by evolution, by examination of conscience.

In the 22 years I have practiced nursing, great strides have been made. Of the approximate 4 million American nurses, 57% begin practice with a bachelor of science while over 18% have graduate degrees. Almost 10% of the workforce identify as male while approximately 25% come from minoritized groups. Nearly 300,000 advanced practice nurses provide primary care. The caps are long gone. So is the tradition of standing when physicians enter rooms.

As the pandemic has highlighted, the nursing profession, the largest of all segments of health care providers and still predominantly female, has a long way to go to achieve equity with physicians, but we have made significant progress. Pride in the profession, despite pandemic fatigue, remains robust.

Ernest Grant, president of the American Nurses Association and the first Black man to hold the position, speaks for many the weary nurse when he wrote that he has "never been more proud to be a nurse."

Nursing unions give clout to the professional pride. Speaking from a position of collective power and responsibility, nurses organized to demand safe working conditions for their patients and for their colleagues. Professional equity has yet to be achieved, but we are closer.

My tentative rapprochement with Catholicism preceded the pandemic by about three years. After 20 years of gratifying but unadorned practice with the Quakers, I missed ritual, sunlight through stained glass, lingering incense. I had heard positive stories about a church just north of the Chicago border and I entered its back door on a November Sunday, during its monthlong commemoration of the days of the dead.

Photos and mementos of loved ones filled the church. Stringed instruments accompanied the piano music and window prisms glowed. The intercessions invited solidarity with the "prayers in the hearts of prisoners." A public health nursing educator who also practices as a hospice nurse, my heart surrendered and I was filled.

But the altar, the focal point of liturgical action, remained resolutely male, unchanged in my absence. Women read psalms, intercessions, but not the Gospel. And they did not ascend the lectern to offer their thoughts about the readings. Such activities remained strictly segregated and the sole province of men. After so many years sitting in Quaker meetings where women's voices commingled with men in lieu of a clergy, in recognition of that of God in every one of us, this apartheid system was difficult to reconcile with the human rights revolution exploding around us.

And it was strangely familiar, this denigration of female wisdom and power. It reminded me of nursing, circa 1970s. A religious version of Brigadoon — lovely and beckoning but strangely untouched by time, by evolution, by examination of conscience.

One Sunday during that first year "back," a kind and gentle deacon offered a homily in which he acknowledged his discomfort with the church's tenacious misogyny. He vowed to work to rectify it and invited like-minded individuals to his home for further discussion.

Advertisement

Ten of us answered the call, many long-term parishioners who had petitioned for women in the diaconate years ago, until an intransigent cardinal made clear the futility of their aspirations. But he was long gone and so they returned, ready to commit once more.

But when we gathered, the women were mostly silent as the men debated dogma. The vision went no further than reopening discussion of women in the diaconate. It felt hollow and unsatisfying. One of the other women, whom I did not know, smiled at me, and I made note of her name. Driving home I recalled Audre Lorde's caveat to those who work for change: "The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house."

I emailed the woman who smiled. Would she be interested in talking further? She invited me for tea with a small group of women in the parish, some of whom had invested much energy and time in the failed diaconate quest years ago.

I expressed my deep dissatisfaction with the oft-repeated mantra that the church changes at glacial speed, that the transformation we desire we will "never see within our lifetimes." Such thinking was both archaic and self-defeating, especially as the glaciers melt around us and we are all too aware of the urgency of our times. We drank our tea. We reconsidered.

We grew to become Equality for Women in the Church, a parish-based group with two subcommittees, on inclusive language and women's voices. We meet monthly and have sponsored several programs, including an intergenerational panel of Catholic women's voices and a showing and discussion of "Knocking on Closed Doors," a video by Kate McElwee of the Women's Ordination Conference. On Mother's Day 2020, we asked the congregation to wear white and handed out white ribbons in support of women's ordination — full equality and equity within the church.

We also organized an action on the day of the seminarian collection fund, reading a statement calling for full inclusion in the priesthood and asking people to stand in solidarity for an end to systemic oppression. Everyone in the full church stood except the priest, who remained seated.

Currently, we are organizing informal "Come to the Table" discussions, inviting people of any gender expression to join together in unfiltered dialogue. Nearly 50 people attended the last, including one of the priests.

Ask a nurse who has practiced through this pandemic the quickest route to moral distress, and they will tell you it comes when asked to act in a way we know to be wrong, that does not comport with our values, but we feel powerless to do otherwise. Ask a community organizer the first step toward change and they will attest to the power and momentum of movement. Our Equality for Women in the Church group has taken action. We no longer lament change we will not see. Glaciers are melting. Women are rising. We stand taller.

Until women of the church unionize and call cardinals to the bargaining table, this will suffice. I am not leaving again. And I am not entering a convent until they are indistinguishable from rectories, with gender-neutral bathrooms and welcoming to all God's children, no exceptions.