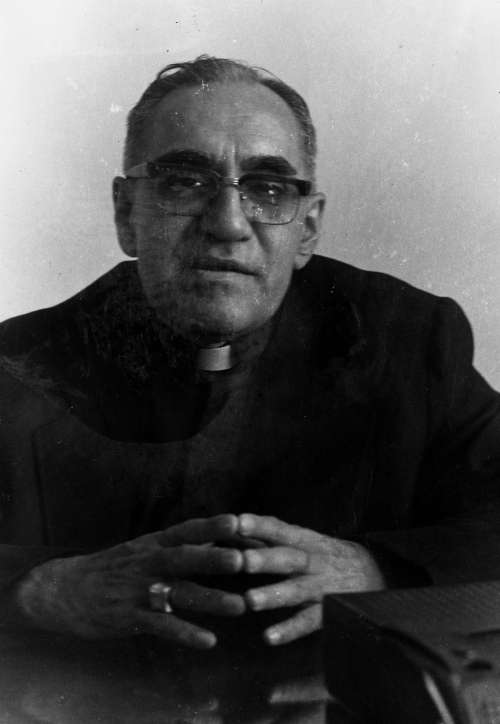

St. Óscar Romero in 1979 (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick)

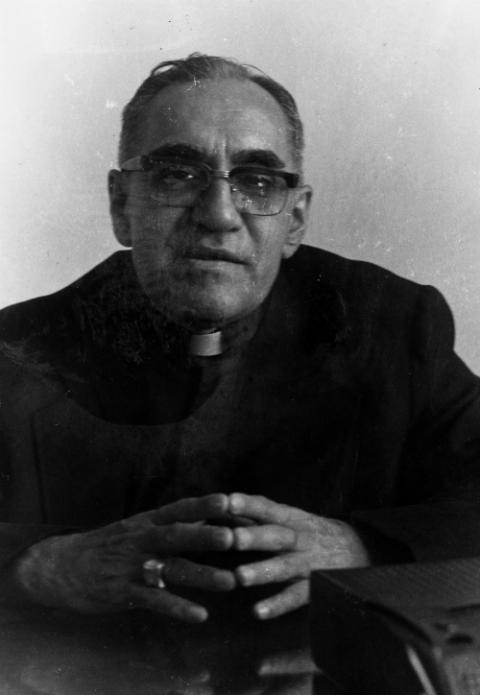

St. Óscar Romero in 1979 (NCR photo/June Carolyn Erlick)

As the U.S. Catholic Church meanders about in its attempt to respond to the ongoing threat to Black men's lives, I can't help but think of Óscar Romero's last Sunday sermon on the day before he was killed. Archbishop Romero, now San Romero de las Americas, is often remembered for his defense of human rights and insistence on society putting the poor front and center.

Romero is a revered martyr, but it is easy to forget the proximate cause of his murder. In that sermon, he went beyond his weekly denunciations of human rights abuses, and explicitly called out for the Salvadoran security forces to disobey unjust orders to repress and kill their people.

Think about that. A Catholic bishop publicly called on the police, the national guard, and the army to defy orders to gun down their fellow citizens. His words were considered treason. Right-wing death squads dispatched the San Salvador archbishop the very next day, with a bullet to the heart as he celebrated Mass.

Earlier this month in the United States of America, we saw two police officers in Buffalo, New York, knock a Catholic Worker activist to the ground, while they were obeying orders, sending 75-year-old Martin Gugino to the hospital.

In Syracuse, New York, we saw a cop, obeying orders, knock a news photographer to the ground on live video. The cop was following orders.

In the nation's capital, we saw security forces, again obeying orders, as the president of the United States had them violently clear peaceful demonstrators from the public square so that he could make a campaign video in front of a church.

Such times bring to mind the last words of Romero's sermon, given in a packed cathedral in San Salvador on March 23, 1980, 40 years past. He spoke plainly, as was his custom:

I want to make a special appeal to soldiers, national guardsmen, and policemen: each of you is one of us. The peasants you kill are your own brothers and sisters. When you hear a man telling you to kill, remember God's words, "Thou shalt not kill." No soldier is obliged to obey a law contrary to the law of God. In the name of God, in the name of our tormented people, I beseech you, I implore you; in the name of God, I command you to stop the repression."

Romero left the cathedral that day a marked man.

We have heard from a few of our bishops about the need to end racism, and for police violence against Black men to stop. Bishops elsewhere have knelt, and marched, and preached justice.

Advertisement

But for the most part, prudence, not prophecy, has seized the episcopate. If Archbishop José Gomez's May 31 statement on behalf of the U.S. bishops is indicative of their collective sentiment, we are leaderless. The missive was essentially a call for prayer and reflection, leavened with four paragraphs lecturing angry Black people to avoid violence.

These are the same half measures taken after the deaths of Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Michael Brown and hundreds of others dating back decades. Rather than praying for the dead, it is time for the bishops, at least one of our bishops, to stand up, as Romero did.

Most are sitting down. Bishop Salvatore Matano of Rochester, New York, called upon the faithful to pray. "Don't you think the time has come to pray," he asked in a May 31 homily, "and to pray seriously?"

Calling upon the faithful to pray, even to pray seriously, is about as safe a place that a religious leader can hide. It is also a good way to ensure that nothing changes.

Far better would be to turn eyes to the south and heed the example of Romero.

Who will be the first U.S. bishop to look at his congregation, including the police officers in the pews, and address them with the passion of San Romero, "I beseech you, I implore you; in the name of God, I command you to stop the repression?"

[Ed Griffin-Nolan is a writer, journalist, and activist who worked in Central America for many years. He is the author of the soon-to-be released book Nobody Hitchhikes Anymore.]